The post “Is it Paranoia? Is it Real?!”: Death Grips, Alternate Reality Games and the Hive Mind appeared first on &.

]]>Death Grips’ is a difficult music group to describe but many like to call them an “experimental hip hop group”, a category seemingly contrived for a group that resists classification through their mixing of different genres. Although the assignation of a genre is sometimes reductive, the “experimental” part is apt for describing the expansive nature of Death Grips’ approach to building an artistic identity that reflects their engagement with different types of media and internet culture. Their website thirdworlds.net hosts self-made videos, graphics, links to their social media, remixes and many of their albums available for free download. The latter has gotten them into trouble when dealing with traditional band management and music distribution. Since their formation Death Grips have often made their music available to fans free of cost, encouraging them to make use of the raw material of their albums for remixing. This broadened their audience but also complicated matters when they signed with Sony subsidiary Epic Records. Death Grips’ mode of self fashioning as an “open collaboration with the world”[1] didn’t mesh well with a traditional model of music distribution and their fraught relationship with Epic came to a breaking point when they leaked their third album ahead of its release date for free. Not only was the album free but Death Grips placed it under Creative Commons CC by 3.0 which means that the album is free to circulate, remix or even sell by anyone. Needless to say, this led to Death Grips being dropped by the label. However a peculiar part of the story occurred before this break, when an Alternate Reality Game allegedly authored by Death Grips appeared on the internet. What emerged from the union of ARGs and Death Grips is a network of connections that implicates media, music, gaming, cultural technique, art and agency.

In August 2012 Death Grips were completing their anticipated third album. Fans on 4chan’s music forum discovered a mysterious post by an anonymous user. A picture of Death Grips front man MC Ride was posted, accompanied by a link to an encrypted archive file on the TOR network. This was the entry point for a five day trip down the rabbit hole[2] of the Death Grips version of an Alternate Reality Game (ARG). Interested players decrypted the first file which contained an image and a text file, both of which contained coded messages, upon solving these more clues were communicated by an unknown mediator. The knowledge base required to move forward in the game was extensive, including ciphers, various codes (Braille, Morse) and navigating through different browsers and websites. There was even some telephone tag involved. Players communicated their findings, speculations and strategies on the /mu/ forum and tried to determine if the “Event” of October 23 presaged by the mediator was the release of Death Grips’ third album or something more. The game ended with more of a whimper than a bang when the instrumentals for Death Grips’ second album The Money Store were released without further clues or communication. Players were left wondering if the game even had any direct link to Death Grips although the release of previously unavailable music would suggest they had a hand in it.[3]

Death Grips “Guillotine (It goes Ya)”

The Death Grips ARG is takes its cue from existing ARGs in terms of tone, but differs in that it has less of a narrative thread. One of the most successful ARGs called The Beast had this enigmatic quality but still centered around the narrative of a murder mystery. Players themselves may have no particular intent of becoming story tellers but each code cracked by a player unlocks another clue and contributes to the advancement of the plot. One of the reasons why The Beast is still recognized as one of the best ARGs is because the number and skill of the players was such that they were able to get a step ahead of the narrative. These contingencies may also be unaccounted for by the games creators and puppet masters who lay the foundations for the game but may also have to adapt to the direction the game takes by altering the plot. It’s from these moments of narrative swerve that the game takes on a life of its own, that “the symbolic is incorporated into the real.”[4] The game operates on this “hive mind”[5] principle, which is mirrored in Sebastian Vehlken’s elegant analysis of swarm as cultural technique: “Collectives possess certain abilities that are lacking in their component parts. Whereas an individual member of a swarm commands only a limited understanding of its environment, the collective as a whole is able to adapt nearly flawlessly to the changing conditions of its surroundings.”[6] The mobilization of the players through technique makes categories of agency and authorship more diffuse. Players and game creators work together as story-builders. No one has absolute authority over the narrative of the game; rather the narrative is generated by the minute actions and reactions of encoding and decoding between groups. It’s a narrative mode that blurs the distinctions between author and audience, right down to the techniques used. A player may not know how to tell a story but by picking up a phone call or reading code they advance or complicate the story.

Can an ARG be art? If all art can be said to operate and be constituted by a series of operations, than what are the distinctions that elevate other forms of art such as literature and film above hacking, coding and gaming? Siegert discusses the traditional conception of culture as class and text based and looking at techniques and operations as a way to usurp the “sovereignty of the book”.[7] Why is writing text imbued with a spiritual essence that is seen to be lacking in the signs and codes associated with science and mathematics? Kramer and Bredekamp suggest a perceived unintelligibility in formulaic text, “Language surrenders its symbolic power in its pact with numbers and becomes a quasi-diabolic technique.”[8] For Death Grips, the spiritual and symbolic is strengthened and invoked through the technical and non-discursive. As artists they are interested in resisting the relegation of their work to music, calling themselves a “conceptual art project anchored by sound.”[9]Perhaps this is why an ARG appealed to them as a method to connect with their listeners and involve them in the construction of their project. The alternate reality component demonstrates a dialectical relationship with reality. The appeal of an alternate reality game is that operates from both a willful immersion in the fictive elements of the game and a real life component that allows them to physically interact with the game like a letter, text message or taking a call from a public phone. Players have a saying “TINAG”[10] or “This is not a game” a suspension of disbelief that we would employ while reading a novel and a concept that implicitly acknowledges the artifice of technique in its very utterance. The instances where the game crosses into the physical space incites a contemplation and examination of what we take to be reality.[11]

One of the interesting aspects of ARG gaming is the power dynamics involved between player, creator and game. Players react to each new development or clue but they each play a crucial part in advancing the game without much room for evaluation or understanding the ends of the game. In discussing Bourdieu’s concept of ‘habitus’ Sterne suggests the fascistic undertone inherent in organized physical movement in things like marching drills and dances. Although not as extreme, ARGs involve a similar kind of inexorable movement that demands to be enacted before players can fully comprehend what they are participating in. There is a certain disturbing element to this process of creation which moves relentlessly forward, generating itself from repetitive technique. The game is created through what Siegert refers to as “processual”[12]definition. It reproduces itself in game play. So who has agency in this particular field? Who controls the game and to what ends? What kinds of capital influence the game? Although ARGs are touted for their creative, collective approach to social organization and problem solving as well as an integration of art and science, their popularity makes them subject to commodification. McDonalds is one of the latest to recognize a money-making trend and try to capitalize on it with their own ARG. In the case of Death Grips, a group that seemingly cares so little about capital they give their product away it is tempting to see them as rebellious dissemblers of an outdated system. This system has already been fractured by the change in the listening habits of the consumer as the physical interaction with music changes from analog to digital. Although we listen to music we may not see a physical copy of an album anymore or even pay for it. Death Grips could be seen as a wrench in the network of organized actions required to sell records. Rather than fight the current state of music consumption, they adopted the hacker role by releasing their music freely and exposing the limitations of the music by turning the subculture on themselves, getting fans to use their decoding skills to participate in the promotion of their album.

But is this really a subversive technique if it is used for the purposes of marketing? Is this simple appropriation of internet subcultures for an aesthetic or can it be an innovative example of cultural technique that complicates the ‘habitus’ of the music industry and contributes to Death Grips’ claim to artistic integrity? In the case of Death Grips the ARG is part of their aesthetic, but also a marketing tool for their music which targets an audience that belongs to this hacker subculture. Does this appropriation of cultural technique undermine the subversive spirit of hacking? Bourdieu’s concept of ‘habitus’ is described by Sterne as “embodied belief” somewhere between objective and subjective. [13] This is how ARGs as cultural technique operate. When we operate in non-discursive ways does the irresistible forward movement of performing a series of operations limit occasions for critical perspective? Agency? Is it paranoia? Or is it real?

[1] Zach Hill, Pitchfork interview.

[2] Unfiction.com

[3] http://img6.imageshack.us/img6/6638/deathgripsnolovedeepweb.png

[4] Siegert, 60

[5] Volroth, 8

[6] Vehlken, 111

[7] Siegert, 57

[8] Kramer, Bredekamp, 22

[9] http://pitchfork.com/news/55781-death-grips-break-up/

[10] Unfiction.com

[11] Siegert, 62

[12] Siegert, 60

[13] Sterne, 375

References

“Glossary” Unfiction.com Alternate Reality Gaming. Unfiction.com, 2011. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

“Death Grips No Love Deep Web ARG.” Imageshack. Imageshack. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Berhard, Siegert. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture and Society. 30.6 (2013): 48-65. Sage Publishing. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Clifford, Stephanie. “An Online Game so Mysterious its Famous Sponsor is Hidden.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 1 April 2008. Web. 10 Oct 2015.

Death Grips. “Lord of the Game (ft. Mexican Girl).” Exmilitary. Death Grips, 2011. Mp3.

Death Grips. “Guillotine (It goes Ya).” Online music video. Youtube. Youtube, 26 Apr. 2011. Web. 12 Oct 2015.

Hill, Zach. Interview by Jenn Pelly. Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media, 2012. Web. Oct. 6 2015.

Kim, Jeffrey Y., Allen, Jonathan P., Lee, Elan. “Alternate Reality Gaming.” Communications of the ACM. 51.2 (2008): 36-42. ACM Digital Library. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Kramer, Sybille and Horst Bredekamp. “Culture, Technology, Cultural Techniques- Moving Beyond Text.” Theory, Culture and Society. 30.6 (2013): 20-29. Sage Publishing. Web. 6 Oct 2015.

Larson, Jeremy D. “Turns out you can make money off of Death Grips’ new album NO LOVE DEEP WEB.” Consequence of Sound. Consequence of Sound, 3 Oct 2012. Web. 8 Oct 2015.

Minsker, Evan. “Death Grips Breaks Up.” Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media, 2 July 2014. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Pocketsonswole. “Birds=Beck??” Reddit.com. Reddit Inc. Web. 12 Oct. 2015.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Bordieu, Technique and Technology.” Cultural Studies. 17.3/4 (2003): 367-389. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Vehlken, Sebastian. “Zootechnologies: Swarming as Cultural Technique.” Theory Culture and Society. 30.6 (2013): 110-131. Sage Publishing. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Vollrath, Chad. “Mimetic Totem, Mimetic Taboo: Adorno’s Theory Of Mimetic Experience And Alternate Reality Gaming.” Conference Papers — International Communication Association (2008): 1-29. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 13 Oct. 2015.

The post “Is it Paranoia? Is it Real?!”: Death Grips, Alternate Reality Games and the Hive Mind appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Kanye West Phonotext: sampling, sharing, re-appropriation and racism appeared first on &.

]]>As a “graduate candidate” in literary studies, I often ask myself whether my analyses of unpopular, neglected poems, novels and plays are culturally relevant. This short essay considers some things that are perhaps too often ignored by English scholars — the immense relevance of American popular music, how music relates to current trends in culture and consumerism, and the manner in which most ideological and aesthetic exchanges occur in the phonotextual virtuality of the internet. In an interview on “Sway in the Morning,” Kanye West claimed that nobody can achieve more cultural relevancy than a “rap rockstar.” And it might be that Kanye is not completely wrong; he may even be right! Jason Birchmeier, a contributer at allmusic.com describes West as: “Far and away the most adventurous (and successful) mainstream rapper of the new millennium, changing his sound and style with each new album.” But when I think about Kanye, I don’t think “musician.” As can be attested to by those of you (suckers) that went to see him live at the Bell Centre last February, West thinks of himself as much as a clothing designer, a poet, and a visionary as he does a rapper or music producer. Part of this “rap/rockstar’s” success, according to Sway, is demonstrated in West’s capacity to “manipulate the internet,” to draw attention to the Kanye brand through the avenues of fashion, through YouTube, through paparazzi scandals, and so on. All of this demonstrates that in the world of hip-hop, cultural “relevance” does not merely rest in selling albums, nor does it rely on getting people to listen to mp3s; more important (at least to Kanye West) is in connecting looking with listening, in drawing phonotextual links between these virtual conglomerations.

In Jonathan Sterne’s terms, the internet has introduced “new praxeologies of listening,” permitting music to be more than a container of containers (as Sterne describes the mp3), but a platform of outward links. Sterne describes how the mp3 marks a change in the economy of musical exchange, introducing a situation where “data could be moved with ease and grace across different kinds of systems and over great distances frequently and with little effort” (829). But this “possibility for quick and easy transfers, anonymous relations between provider and receiver, cross-platform compatibility, stockpiling and easy storage” (829) is old news in the world of hip-hop. For decades, hip-hop has relied upon an interactive collective phonotext exceeding sound. As Jeff Chang shows us in his insightful “History of the Hip-Hop Generation,” the musical innovations of spread like fire in the late-70s: “cassette tapes passed hand-to-hand in the Black and Latino neighbourhoods of Brooklyn, the Lower East Side, Queens, and Long Island’s Black Belt” (127-28). Hip-hop has always been a “hyperlink” musical genre. When it comes to rhymes, breaks and beats, the logic of rap eludes most of the rules of “intellectual property” that constrain scholars in academic institutions. Borrowing, sampling, sharing and stealing are in fact crucial parts of the collaborative “phonotexts” that hip-hop inevitably opens up. According to Greg Tate, the hip-hop generation is always “about ten years ahead of culture in terms of embracing [and utilizing] technology” (43). We see how hip-hop takes the music sample to embody “an item that ‘works for’ and is ‘worked on’ by a host of people, ideologies, technologies and other social and material elements” (Sterne, 826). Drawn out of the noise of the internet and ripped from previous songs, the sonic trafficking done by DJs does not produce original scores so much as generating remixes and re-appropriations of previously recorded media. Social and material relations are always at the centre of the music. And as we see with the example of Kanye West, the lyrical emphasis on consumerism, race, and oppression are inextricable from the formal operations of technology, advertising, distribution, performance, and so on.

“Annotate the World” : Welcome to Genius

Sterne uses the mp3 as a “tour guide” through social, physical, psychological and ideological phenomena of which otherwise we might not have been fully aware; this essay uses Rap Genius as a means to discuss the same phenomena. “Annotate the world” is the Genius mantra. Search the relational database and you will discover a “world of communities,” each fixated on their own phonotextual genres (channels range from R&B genius, rock.genius; country.genius; news.genius; lit.genius; history.genius; law.genius; sports.genius; to many others). The site displays shifting narratives which vacillate between the critiques, rants and appraisals of participants. Everyone is eligible for an account, which allows for maximum participation in the collaborative annotation of the lyrics, aesthetics, production, and intertextual reference that occurs within and surrounding the thousands of featured songs. Rap Genius shows us how the internet can be used to organize, expand and store data about hip-hop, its history and relates all of this to current events. We also see how the interactive, visual, imaginative extensions of music take us outside the “contained” space of the mp3, beyond what Sterne describes as the “fine distinctions of the human ear” (834). Rap Genius, like the mp3, has altered the nature of the music recording industry as well as the actual and idealized practices of listening. Rap Genius is an internet hypertext mapping and storing the contours of hip-hop; it is an exegetic phonotextual knowledge base that is both structured and always open to alteration.

LOOP ONE : “New Slaves”

Sterne discusses mp3s as “cultural artifacts in their own right,” as a “psychoacoustic technology that literally plays its listeners” (825). As a means of testing the “Genius,” I began browsing the web pages associated with a couple of tracks from Kanye West’s newest album entitled Yeezus. How do fans and critics play with Yeezus? How does the mp3 “container,” in tandem with web-based music discussion boards open a situation where listeners, consumerism, culture and music play off each other? After all, “music” describes more than listening, viewing, sharing, trading, and stealing audio files, but represents a cultural dialogue — and in my view, this intercommunication needs emphasis. Thus how do the perplexing, ambiguous and infuriating messages of Yeezus escape simple hermeneutic interpretation, and demand an expanded virtual phonotextual analysis? Yes, Kanye sometimes raps like a misogynistic egomaniacal, elitist asshole, but this does not mean that his product is not of immeasurable capitalist and cultural value. If we are going to talk about “big data,” mass media, capitalist production via the phonotext, why not turn to the “rap rockstar” that ostentatiously proclaims “I am a god”? In the spirit of “distant reading,” as I browsed the site theory synchronized with scores of other cultural objects, feelings and images. Images of West’s clothing line led into vertiginous accounts of the American white establishment; ethics, bling, racism, politics, hate, hope, America. To view albums as single “containers,” as “cultural artifacts” is to ignore larger debates of what the world of music is doing. Rap Genius invites a formal analysis of music that acts, and thus aids in uncovering how a world of listeners are making sense of the larger controversies embedded within Kanye’s phonotext.

check out the link; you might even participate in the forum!

Here is a supplementary explanation about why Kanye thinks “we are all slaves”:

LOOP 2: “Blood on the Leaves” [Annotation from Rap Genius]

Sterne claims that the iPod introduced new ways of listening to music; and although mp3s are assembled by a variety of technologies, Sterne cites Philip Sherburne, that computer manipulation demonstrates “the ongoing dematerialization of music” (831). But when we listening to music through the channel of Rap Genius, what sorts of rematerializations occur? Take, for instance, “Blood on the Leaves” — where Kanye’s narcissistic lamentation about a break-up rematerializes the entire track of Nina Simone’s “Strange Fruit” — a mournful song about the lynching of countless African Americans. Jody Rosen criticizes the rapper is “well aware of how audacious it is to interpolate that sacred song into a monstrously self-pitying … melodrama about what a drag it is when your side-piece won’t abort your love child.” Meanwhile, the responses on Rap Genius include several extra-textual references that might help to make sense of the broader context of the song. One of the links posted is this video:

Rap Genius extends Jonathan Sterne’s evaluation of the “peculiar status of the mp3 as a valued cultural object which can circulate outside the channels of the value economy … enabling conditions for the intellectual property debates that surround it” (831). Kanye’s sampling of “Strange Fruit” ignites more than a conflict about intellectual property, but draws our attention to the reappropriation of a historical and cultural artifact, in this case one that explicitly speaks about the slavery and murder of countless African Americans. Although the original message of “Strange Fruit” is obscured by Kanye’s self-involved contemplations and the tight production of an aesthetically-pleasing song, Rap Genius displays how the phonotext cannot evade these illuminating and necessary debates.

LOOP 3:”Black Skinhead” (I recommend that you read the full Annotation for this one)

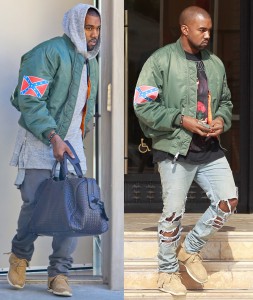

These are certainly not the first exemplifications of Kanye West’s words producing arguments about racism. But with Yeezus, merchandise may have generated as much public discussion about race than did the lyrics of his songs:

Through the “Genius lens,” merch becomes another component in the phonotextual narrative; although these images conflate and confuse matters, they also draw us back to the music. The jam’s provocative title is well-summarized by the Rap Genius community. (I found the link to the wikipedia entry on skinhead to be a very informative annotation for this track). As we have already developed, the re-appropriation (resyncing, remixing, re-defining) of symbols, iconography and lyrics (from the sacred to the profane) is one of Kanye’s greatest skills. These are, after all, perhaps the crucial components of any relevant phonotext — at least in the virtual world of pop. But can we take srsly this self-proclaimed “god,” this modern-day “Yeezus”? But when I turn to the news.genius channel, Zach Schwartz has this to say: Applaud Kanye West for Wearing the Confederate Flag

To conclude, Rap Genius offers more than some interesting table talk about sharing, sampling, re-appropriation, and racism. Kanye certainly “ain’t got the answers!” But at least phonotextual platforms such as these are getting us all to dig.

Works Cited

Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Reading: Ebury Press, 2007. Print.

Cross, Brian; Mark Anthony Neal; Vijay Prashad; and Greg Tate. “Got Next: A Roundtable on Identity and Aesthetics after Multiculturalism.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. 33-51. New York: Basic Books, 2006. Print.

“Kanye West – Black Skinhead.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – Blood on the Leaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – New Slaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Manhatten, Chris. “Kanye West Flips Out On Sway In The Morning Interview Nov 26th, 2013.” YouTube. YouTube, 27 Nov. 2013. Web. 1 Nov. 2014.

Maya, H. “Nina Simone – Strange Fruit.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 29 Mar. 2011. Web. 7 Nov. 2014.

Rosen, Jody. “Rosen on Kanye West’s Yeezus: The Least Sexy Album of 2013.” Vulture. New York Media LLC., 18 June 2013. Web 20 Oct. 2014.

Schwartz, Zach. “Applaud Kanye West For Wearing the Confederate Flag.” News Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 7 Nov. 2013. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Jonathan. “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media and Society 8.5 (2006): 825-842. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

West, Kanye. Black Skinhead. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.

—. Blood on the Leaves. Grooveshard, 2013. Stream.

—. New Slaves. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.

The post The Kanye West Phonotext: sampling, sharing, re-appropriation and racism appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

]]>When it comes to listening to vinyl, NYC artist Rutherford Chang antithesizes what Franco Moretti identifies as the “typical reader of novels” in Britain up to about 1820 (Moretti 71). Instead of “a ‘generalist…who reads absolutely anything, at random’” (Moretti 71, quoting Albert Thibaudet), Chang listens to and collects anything, mostly at random, of a very specific corpus: copies of just one edition of one album, “the Beatles[’] first pressing of the White Album” (Paz np). To exhibit and expand this collection, which currently stands at “693 copies” (out of the over three million copies that comprise the 1968 “limited edition”), from January to March 2013 Chang occupied “Recess, a storefront art space in SoHo. It’s set up like a record store…and visitors are invited to browse and listen to the records. Except, rather than sell the albums, I am buying more” (Paz np). While there, Chang listened to White Albums all day, “recording the albums and documenting the covers” (np). Each record, being vinyl, bears its own record of needleworked grooving; many a cover, being once famously white, has been personalized with doodles. These covers Chang “put up on the ‘staff picks’ wall” – a topographized supercut. As for the records, “[a]t the end of the exhibition, I will press a new double-LP made from all the recordings layered upon each other. It will be like playing a few hundred copies of the White Album at once, each scratched and warped in its own way” (np). In the meantime, Chang released a preliminary effort onto SoundCloud, “White Album – Side 1 x 100”: one hundred White Album Side Ones playing simultaneously.

On what scale is Chang’s a scalar reading project? How does a noisy audio palimpsest multiplying “one” object compare with the pristine genre-spanning graphs of Moretti or the intricate Göethe-corpus topologies cited by Andrew Piper?

It’s tempting to dismiss Chang’s White Album remix as simply the synchronic equivalent of a less sophisticated “vernacular” of distant-reading like the supercut. But Ian Bogost’s proposal that object-oriented ontologists need to graduate from the logocentrism of writings which do ontology in theory, to the carpentry of crafted objects that put ontologies into practice (e.g. 91-2), suggests that graphing-objects similarly needn’t be constrained to the logo-visual. Can the “palimpsest” component of Chang’s clearly praxis-oriented project be considered, then, as “auditorizing” data in the same way that one of Moretti’s graphs visualizes data? A pertinent question, given “today’s growing interest in the field of information visualization” (Piper 388).

After all, what is graphic representation? “Graphing,” as the etymology suggests, is a form of writing, which is a form of drawing. As Piper points out, “Friedrich Kittler’s argument, of the two-thousand-year-old antipathy between the alphabetic and the numerical[,]” is a “false notion” (380). Nonetheless, the invisible Cartesian latticework gridding any typeset page, into whose discursive position of “prose” most writing gets indifferently wrapped, has continuously disarticulated graphemic writing from the genre of alphanumeric graphical representation. Notably the same, however, cannot be said for music. From its earliest forms, well before Descartes and de Fermat, the musical staff makes little secret about its dimensionality: pitch vs. time. But: “non-musical” texts encode sound no less! They, too, graph sounds against time, within a limited repertoire of graphemes (e.g. 26 letters vs. 12 tonic pitches). Thus, while literary analysis may have preoccupied itself with “the two-dimensionality of the page or the three-dimensionality of the book” (Piper 383), its broader problem has been that it would not even have articulated its conceptions of the page and book as such, for only recently has it begun to consider its objects in dimensional terms whatsoever. Meanwhile, graphing (alphabetic writing) and graphing (alpha-numeric charting) and graphing (musical scoring) have remained distinct. And a musical graph is expected to be performed aloud, with the body, whereas a philosophical or statistical graph is expected to be performed in silence, with the head. Cartesian plane indeed.

Sound, in short – by which I don’t mean speech – has been systemically excluded as a medium for philosophy, let alone for demonstrative data representations, and this has everything to do with philosophy’s logocentric tradition in emphasizing content over form, music being strongly articulated to the latter. But if we re-articulate the above various forms of writing as graphings more broadly, can we then likewise re-articulate any performance of a graphing as itself a form of graphing, even if this performance is sensually other to the visual (as the iconized data of Piper and Moretti, despite their iconoclasm in other respects, tends to emphasize)?

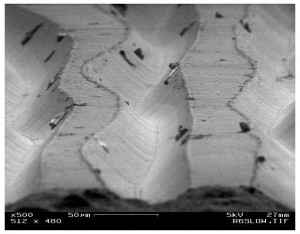

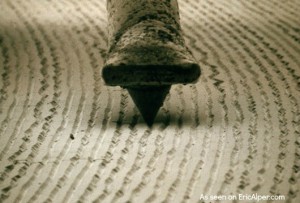

Things become clearer if we elaborate further on what graphing (i.e. writing) is, and illustrate with vinyl. In Vilém Flusser’s description, “writing…was originally an act of engraving. The Greek verb ‘graphein’ still connotes this…. [T]o write is not to form, but to in-form, and a text is not a formation, but an in-formation” (Roth 26). It is such information that we find grooving a vinyl record: a form of information whose curves, unlike these graphemes that I type, is more readily articulable to the curves of information that discourse has arbitrarily distinguished as graphing (see Figs. 1 & 2). Indeed, confusions have arisen at all because we speak of information in such logocentric terms as Flusser himself does, whereas information theorists speak of it in terms of waves, frequencies – something that writers like Piper do evoke with statements like, “any textual field is at base a configuration of differential repetitions” (394). Whereas, now that we’ve re-articulated graphing as information, we can see how the curves of Figure 2 could just as easily be transfigured into audio as could the curves on the vinyl. It would be up to us listeners to re-articulate our logo-visual biases to interpret the “audiograph” as well as we can its visualized score. But is it just our lack of familiarity with interpreting an “audiograph” as a graph that would other it as comparably “messy” (in John Law’s term), or can such graphs simply not compare with pristine Cartesian visuals, say for reasons of transfiguration?

The approach to this question is rolled up in what the convergence of Figures 1 and 2 illustrates: the zero-point at which “distant” and “close” break down into “a continuous spectrum of focalization” (Piper 382). This is a useful place to begin discussing Chang, whose “1 x 100” audiograph intuitively seems more of a “distant reading” than the audiograph from a single record. But, having dismissed the distant-close binary in favour of an ontology of surface relations, we shall see that “more” no longer necessarily means more, nor “less” less. If all graphs record regularities of information, then the question becomes not about perspectival proximity, nor even exactitude, but about how and what each object – 1 White Album vs. 100 White Albums simultaneously – graphs differently. What do the regularities of one single White Album measure in comparison with the overlayed regularities of one hundred White Albums?

Close-distant reading: We needn’t hear 100 versions at once for us to know that our single copy is not singular, that the “object” we listen to is much larger than its packaging’s pretense to unity; indeed, the fact that it is not one-of-a-kind is likely how and why we and the object found each other in the first place. For Foucault, the very fact that we have a White Album playing at all means that it is discursively sanctioned, corresponding to a discursive statement, a regularity within a field of discourse: the grooves of a single White Album already graph a regularity concerning White Albums. Like the statement “QWERTY,” produced by a standard keyboard, any printing of a White Album is a statement produced by a similarly standardized mass-printing device programmed to print the White Album from a “master” copy or image, such that any single vinyl record graphs a regularity of discourse, a record of the process of inscribing White Albums with the grooves that constitute White Album-ness. A White Album graphs, more accurately than its hundred-fold multiplication, the pristine Gaussian “mean” of White Album articulation. Mass production’s claim to mass identity is its mass delusion, but an individual album is nonetheless a graphical index of its mass-media ur-stamp. Indeed, this is so because it is such standardization’s goal: to distribute the closest approximation of the Same, so that a claim for Sameness may be made, a common-place created.

Distant-close reading: What do the 100 albums played at once tell us, then? We needn’t listen to know that there will be much “noise”; indeed, judging by the present recording, if Chang carries through with his plan to mash up his 600+ records, we would hear nothing but noise. What, then, does this audio-topography do? Ostensibly it graphs the relative fluctuations between 100 versions – but not in any distinct way. Can we distinguish all the tracks (and their interrelations) as we might in a visual representation? Indeed, there is “noise” because there is information lost – each element in the audiograph interferes with every other. Or is the noise we perceive as much a function of our bias to the logo-visual? If for topology “the ‘object’ is merely the identification of a visual thickness” (Piper 384), then Chang’s project fits the description, but does this hold if topology considers “reading” only as “a deeply visual experience” (Piper 387, emphasis added)? Alternatively: Friedrich Kittler engages in an alien phenomenology of the phonograph to describe its recordings as constituting the real: “The phonograph does not hear as do ears that have been trained immediately to filter voices, words, and sounds of noise; it registers acoustic events as such. Articulateness becomes a second-order exception in a spectrum of noise” (Kittler 23). Such engagement raises the question: Is (topo)graphing unable to deal with acoustic events as such? Would the noise be better approached from the phenomenology of an alien object?

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 85–111. Print.

Roth, Nancy A. “A Note on ‘The Gesture of Writing’ by Vilem Flusser and The Gesture of Writing.” New Writing: The International Journal for the Practice and Theory of Creative Writing 9:1 (2012): 24-41. Web.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford UP: Stanford, 1999. Print.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 1”. New Left Review 24 (Nov-Dec 2003): 67-93. Web.

Paz, Eilon. “Rutherford Chang – We Buy White Albums.” Dust and Grooves: Vinyl Music Culture. 15 Feb 2013. Accessed 10 Oct. 2013. http://www.dustandgrooves.com/rutherford-chang-we-buy-white-albums/

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.

The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Big Baroque Mess appeared first on &.

]]>For this week’s probe, I’ve decided to look at the printed manuscript of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Six Sonatas and Partitas for Violin Solo,” written around 1720. One main contributing factor to its “messiness” is that nobody really knows when these pieces were composed, and there is little detailed information given on the manuscripts. The incomprehensibility of this work has resulted in each musical interpretation being different, from the first full recording in the 1930s, to live performances of the music today.

John Law first tells us to acknowledge the messiness of knowing. Ok – so I’ve accepted the fact that Bach didn’t really tell me how to play these pieces, and teachers and books have told me I can do what I want with them. But, this makes me question my role as a performer. Am I to be the link between the music and the composer, which would make the written music simply a vehicle for this transmission of ideas? Or, am I to interpret the music as I feel fit, not considering how the composer may have wanted it played?

With regards to the Actor-Network Theory (ANT), this manuscript is a perfect example of how the material affects the social. Law explains heterogeneous networks as ways of suggesting that society, organizations, agents and machines are all effects generated in patterned networks of diverse (not simply human) materials (Law 1992, 380). So, if our interactions within different networks are mediated through human or nonhuman objects, this book of printed music plays an important role in how one acts and behaves within the network. In this case, since Bach died in 1770 and I want to play his music today, in 2013, it is a network of both humans and objects that provides communication between a violinist today and Bach.

It all began with iron gall ink on large manuscript around 1720 (the same ink used by da Vinci, Van Gogh, and to write the US Constitution), to its first publication in 1843, and finally to the modern editions that can be found on the internet today. Within those objects are countless people who made decisions in the early editions: whether to change or add things, what size paper to print on, the overall look of the music, and then there are the performers who affect personal taste preferences in more modern editions. Perhaps an editor really loves one violinist’s version of Bach, and subsequently prints all of their fingerings, bowings and dynamics into their edition. Is it biased? Yes. But, are other editions also biased? Yes. Are the “original” manuscripts that were found in Saint Petersburg sixty-five years after Bach’s death biased? Perhaps. It is unknown if they are even originals, or if his wife may have made copies. From ink on a manuscript, through various forms of printing presses, to being able to find the sheet music through Google today, one can access countless formats of what machines and humans have contributed to the heterogenic patterning of the social. This has quickly turned into a huge network! What a mess.

Now, things just continue to get messier the more I think about the lack of clarity in my probe object. In his article Thick Description, Clifford Geertz states that “the more deeply [your research] goes, the less complete it is.” This is a scary statement to come to terms with, especially since each of us is about to live with our research topic for at least the next several years. When we finally finish our dissertations, we are likely not going to feel a sense of completeness from what we just accomplished. I am sure we will all have questions and unknowns at the end of the process. The areas we have chosen to research are all messy in their own ways, and Law reassures (me, at least) that vague research is not necessarily “bad” research.

Towards the end of his article, Law describes how “some materials are more durable than others” (1992, 387), eventually saying that by performing these relations and materials, they may last longer. Printed music is meant to be embodied – no two violinists will approach the compositions in the same way (Affelder), and therefore the network and actors are continually changing and evolving over time, just as knowledge is as he explains in Making a Mess with Method.

As an example, let’s take a live recording of Gidon Kremer: Gidon Kremer – Bach. This is the third movement from the last partita of the set of six works. We don’t know whether Kremer is performing only one of the six works, or if he is in the process of playing them as a set, as scholars believe Bach intended them to be performed (Fulkerson). Judging by the sweat on Kremer’s face, it looks as if he’s been playing for awhile, which leads me to believe he has just played the five other sonatas and partitas that precede this one (which would take about two hours).

What objects and people make up this social network? There are many actors, such as the choice of edition from which Kremer learned the music, the teacher who once coached him through learning the music years prior, the audience watching this particular performance, or the tempo at which he has chosen to play the piece. But, connected to each of those actors are other networks as well. Each audience member comes in with different expectations of what they’re about to hear. Some of them will have listened to multiple versions and know their preferences, while others will be hearing it for the first time. Does Kremer take into consideration for whom he is playing? Would he perform the piece differently if he knew a particular person was in the audience? All of these factors contribute to the social network at that particular time. As a complete contrast, here’s another example of the same piece played by Gil Shaham – Bach – notice how different the tempo, volume and overall approach is compared to the first clip.

Law describes ANT as a claim that “people are who they are because they are a patterned network of heterogeneous materials” (Law 1992, 383). He goes on to explain that actors are also networks, for example, Law uses as an analogy, a machine that has various parts and roles within it. Back to my example: this would make the printed music an actor as well as a network, and if it is a network acting as one unit, it can disguise itself as a black box of sorts. One can look closely into the networks that are hidden from view (for example, the processes of transformation from hand-written manuscript to computer-processed sheet music), or they could choose to view the object as a single actor as part of a larger network.

Just like the YouTube videos: one could see it strictly as a performance playing an actor role in a social network, or one could dig deeper into the networks that make up and surround the actual performance.

This is still all very messy.

To try and sum up the mess and vagueness, I will discuss knowledge and the various forms in which it can be found. When I hold this book of music in my hand, I know what an important body of musical work it is. The weight and number of pages inside is daunting, but it gets worse when you open it up. One has the choice to either read from the edited version of the “original” manuscript, or to try and read off of the shrunken version of the “original” manuscript. There is a great deal of collaborative knowledge that went into the printing of this edition, which I now know makes things even messier because Law explains that collaborative research is messy because you never fully know what your collaborator(s) know. If I choose to read the edited version, I am consciously playing it the way that the editor (in this case, Galamian), wants me to play. But, I am unaware of what his knowledge was at the time of putting his ideas onto the music. I believe that Galamian’s way of dealing with the messiness of the situation was to include Bach’s manuscripts at the back of the book. It still appears that there is a precise system to it, but one is able to see into the messiness if they so desire. I haven’t even gotten into the argument of performance practice and whether or not Bach’s music should be played on modern instruments, or violins from the period from which the music was composed. That is another pile of mess altogether.

Music is truly a moving target. There will be future editions, and people will continue to learn from past editions. All of these are affected by live performance and recordings, which change along with the trends and what the style at the time of editing is. This shape-shifting reality, as Law puts it, makes it extremely difficult to study and document since it is so heterogeneous and widespread.

On grant applications, I will do my best to present a precise and clear description of my research, but for now and at least for the next few years, I will continue to struggle with the vague and imprecise nature of social sciences research.

Works Cited

Bach, Johann Sebastian. “6 Sonatas and Partitas for Violin Solo.” Edited by Ivan Galamian, foreword by Paul Affelder. New York: International Music Company.

Fulkerson, Gergory. “Unaccompanied Sonatas and Partitas of Johann Sebastian Bach.” Sheila’s Corner, 2000. Accessed 11 September, 2013. http://www.sheilascorner.com/bach.html

Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description.” The Interpretation of cultures; selected essays. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

Law, John. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity,” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 1999. Revised 2003. http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law1992NotesOnTheTheoryOfTheActor-Network.pdf

__. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003. http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-mess-with-Method.pdf

Vittes, Laurence. “Titans Talk about the Bach Solo Violin Works.” All Things Strings, January 2007. http://www.allthingsstrings.com/News/Interviews-Profiles/Titans-Talk-about-the-Bach-Solo-Violin-Works/

The post A Big Baroque Mess appeared first on &.

]]>The post Typewriter/Piano, Poet/Composer appeared first on &.

]]>

The orchestral piece “Briony,” part of the score composed by Dario Marianelli for the 2007 film adaptation of Ian McEwan’s Atonement, is fundamentally a recent addition to the cultural landscape of typewriting. Despite its recency, the piece at its core makes a large-scale, conscious return to the “basics” of early media theory, fusing together classical music and the typewriter in a way which Marshall McLuhan had already conceived of much earlier. McLuhan’s early theories on the materiality of media, specifically from the essay “The Typewriter: Into the Age of the Iron Whim,” make a claim for the inherent connection between music and typewriting, both of which McLuhan consider to be intrinsic acts of composition that share more similarities than they might appear to at first glance.

If poetry – most explicitly in its oral form – manipulates timing, breath, suspension and syllabic rhythm to enhance the experience of both writing and reading a poem, music certainly does the same for any given composition. As McLuhan points out, Charles Olson and other mid-to-late twentieth-century poets employed vers libre to revert the state of language back to the original spoken, unrestrained circumstance of natural speech. If one agrees with Hemingway’s summing-up of the act of writing being as simple as one having to “sit down at a typewriter and bleed,” the poet becomes more like Sammy Davis Jr. than Samuel Johnson in front of his Remington. Indeed, the now-classic “Typewriter Song” by Leroy Anderson embodies the jazzy, uncontrolled essence of the connection between typewriting and music, tying in McLuhan’s and Olson’s conceptions of free verse and the typewriter as the frantic yet most honest means of writing (or “bleeding”) poetry.

However, “Briony” is not jazz, and is not a product of the cultural environment of the mid twentieth-century which, in truth, begged for a sense of freedom and escape from constraints of (largely) any kind. “Briony,” like most classical music pieces, is a deeply calculated, controlled composition which begs for a fixed and finite interpretation on the part of the listener. The piece begins primarily with interweaving notes of a typewriter and a piano. From the outset, the connection between the typewriter and the piano is established (or at least alluded to), consciously or not, by the composer.

Again, if we return back to the “basics” of the theory of writing, it becomes apparent that both acts have fundamental implications which cannot be ignored. As Vilem Flusser points out in “The Gesture of Writing,” the seeming banality of certain details regarding the gestures of written composition become more important in a larger epistemological framework. As such, beneath the banal and the undervalued lies the deeply relevant in terms of our social consciousness and, without returning to the rudimentary, it is nearly impossible to truly comprehend that social consciousness which we assume to be straightforward on a daily basis.

Flusser asserts that writing, in its most primitive and original form, is essentially a scratching or engraving with one material onto another. Though we may have lost or come quite far from the original gesture of writing as engraving, it may be that – if one looks closely – the gesture is still deeply present. In piano-playing the keys imprint, engrave or strike (though not materially or permanently, as the typewriter does) their strings, creating a particular sound which recreates the gesture of writing through musical notation. At the striking of both sets of keys sound is produced and rhythm is established. Both the piano and the typewriter involve the use of hands and fingers extended forward and rested above the keys of each respective instrument, uniting the tactile and sonic human faculties. Posture, and the way that a person places themselves in front of both the typewriter and the piano is extremely similar: both require a formal, rigid positioning of the body. As any first lesson in piano-playing will begin with posture, most early typewriter instruction manuals will dedicate an entire section to describing the ideal body positions for working on a typewriter. More complexly, however, both acts engage the mind in a linear fashion (quite literally, both instruments’ keys are arranged in ordered lines), have trained the mind to use all ten fingers rather than a fist or closed single hand, have given rise to a thought-process which functions in terms of linearity and progression, and have created a deeper connection in which the machine becomes essentially an extension of the physical human form.

What implications does this have on a social, and even on an anthropological, level? What does it mean when the introduction of the typewriter began to affect, modify and transform the way the human body physically interacts with it? Can our physical bodies actually be adjustable according to the materiality of our media?

Of course, it may be that “Briony” employs typewriter sounds in its musical score because Atonement deals largely with writing as a centralized theme within the context of its plot. Still, the continuity between the typewriter and the piano cannot be denied outright, even if the philosophical discourses of McLuhan or Flusser are ignored. To be sure, the continuity between the two goes beyond the fact that both instruments create sound.

On the basis of mood and atmosphere alone, the monotone, hard-sounding “click” of the typewriter’s keys seems to fit perfectly with the haunting, poignant nature of the film’s classical score. Indeed, the music is not only complemented but is accentuated and heightened by the typewriter sounds, adding an element of intensity that, nearly bass-drum-like in its steady rhythm, seems to resemble a death-knell sounding ominously in the background. The “scratching” Flusser associates with early writing has a sense of violence to it that seems to be translated to the typewriter, and by extension, to “Briony.” Why might this be the case? Do we inherently associate typewriting with a seriousness, coldness, monotony and rigidity that seem to shine through with “Briony”? If the gesture of writing, an equally solitary, solipsistic and serious-natured endeavor in itself, is associated with the typewriter throughout the majority of the twentieth century, does the typewriter have some inherently-associated emotional capital which marks our perspective of writing and typewriting? Might the composer be suggesting that the dichotomy between our forms of media continuously leaves ghosts of an abandoned media haunting and impacting our social consciousness? Finally, have we transitioned from the perspective of the jazzy, upbeat connotations of the typewriter which Leroy Anderson’s music seemed to propose toward one of the typewriter as inherently ominous and haunting as proposed in “Briony”?

— Stefano Faustini

The post Typewriter/Piano, Poet/Composer appeared first on &.

]]>