The post Bootcamp: Irish Music Club of Chicago appeared first on &.

]]>Francis O’Neill’s seminal collection Music of Ireland, and Irish Minstrels and Musicians, his principal book on the subject of his collection endeavours, both contain a photograph of Chicago’s Irish Music Club (Irish Traditional Music Archive; O’Neill, 479). The photo is dated as having been taken between 1901 and 1909, and shows 26 members of this club, with each member’s name in a caption below the photograph. Using this club as a case study, one might consider the applicability of network theory to interpersonal relations in circles of Irish traditional music in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Chicago.

The club itself was short-lived. It was formed around 1901; by 1912 “[Francis] O’Neill could say that not even a remnant of the Club remained and that few of the former members were on speaking terms” (Carolan, 39). While the club most likely broke down in the wake of personal disagreements between members, it is impossible to trace with any kind of accuracy the vicissitudes of individual musicians’ relations with each other. Were some friends, others rivals? Did any of these musicians teach tunes to some of the others? During the years of the club’s existence, each musician could have met with any other on a number of occasions, and interacted with him in myriad different ways. This leads to the conceptualization of something like Figure A in the document below.

Figure A depicts all 26 musicians as vertices, as well as all 299 edges connecting each musician with every other one. It ultimately represents a mere matrix of acquaintance. Each musician in the photograph would have at least been aware of the existence of every other one, and therefore could have interacted with him. This network diagram can then be viewed as a map of potentiality. We do not and cannot know – beyond the imperfect, patchy traces of written records – the details of who spoke to whom, nor for what length of time their acquaintance lasted. Nor could we accurately present this information in a network diagram, were it even available. These edges are thus not weighted and have no direction, to borrow Moretti’s phrase (Moretti, 3).

It is worth emphasizing that the network diagram in Figure A makes no reference to the broader network of musical transmission and interaction within which Chicago’s Irish Music Club existed. It is embedded in the broader global assemblage of practitioners of Irish traditional music, as well as that of historical Irish-American ethnicity. These overlapping and crisscrossing networks may be interpreted as a rhizome, whose points “can be connected to anything other, and must be” (Deleuze and Guattari, 7).

In Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Francis O’Neill recounts some interactions between the Irish Music Club and some external actors. To imagine these interactions as a network, the 26 vertices of Figure A may be conceptually lumped together in Figure B to create a vertex representing the club as a whole. Figure B then serves to illustrates a tiny slice of the club’s history. This second network diagram depicts the interactions of four individuals with the Irish Music Club at some point in its history. While Figure B does indicate some degree of contact, it does not reveal anything meaningful about the nature of the interaction. It does not show, for instance, that Rev. Richard Henebry and Rev. William Dollard visited Chicago in 1901 and mingled with some of the club’s members (O’Neill, 178), nor that John Coughlan, an Australian player of the uilleann pipes, arrogantly asked the Club to help him fund a journey to America (O’Neill, 253), nor that Australian fiddler Patrick O’Leary bemoaned in a letter that he could not partake in the music and companionship of Chicago’s Irish Music Club, as he was stuck in Australia (O’Neill, 383). The details remain textually tethered.

My last bootcamp, on O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, failed completely. This attempt seems more successful, but not by much. Figure A illustrates quite well the complex and ultimately unknowable potential interplay between some members of Chicago’s Irish Music Club. Wershler, Sinervo and Tien consider the intricacies of studying “cultural practices that you’re not supposed to know about” (A Network Archaeology of Unauthorized Comic Book Scans). While their focus is the digitization of comic books, their interrogation also seems to apply to the subject at hand. I would simply rephrase their question to: “How you do study cultural practices that you can’t know about?” One answer is to simply map out every possible edge, to highlight the network’s potential complexity.

Figure B, on the other hand, offers a clear depiction of Francis O’Neill’s accounts of the Irish Music Club’s interactions with external actors. This depiction is useful in that it positions the people involved in relation to each other in an intelligible way, but remains problematic due to issues of traceability. However this does not prevent, as I wrote in my last bootcamp, those fragments of available evidence from enacting instances of cultural convergence.

Works Cited

Carolan, Nicholas. A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago. Cork: Ossian Publications, 1997. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. “Introduction: Rhizome.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Massumi, Brian. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 3-25. Print.

Irish Traditional Music Archive / Taisce Cheol Dúchais Éireann. “The Irish Music Club of Chicago, ca. 1901-1909 / unidentified photographer.” http://www.itma.ie/digitallibrary/image/irish-music-club-chicago

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab Pamphlet 2. May 1, 2011. [Orig. pub. New Left Review 68, March-April 2011]. http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf

O’Neill, Francis. Irish Minstrels and Musicians, with numerous dissertations on related subjects. Chicago: The Regan Printing House, 1913. Print.

Sinervo, Kalervo, Shannon Tien, and Darren Wershler. “A Network Archaeology of Unauthorized Comic Book Scans.” Amodern 2: Network Archeaology (fall 2013). http://amodern.net/article/a-network-archaeology-of-unauthorized-comic-book-scans/

The post Bootcamp: Irish Music Club of Chicago appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot camp: (In)Corporations of Fairy Tales in ABC’s Once Upon A Time appeared first on &.

]]>Moretti argues there is at least one “consequence of [the network model] approach: once you make a network of a play, you stop working on the play proper, and work on a model instead: you reduce the text to characters and interactions, abstract them from everything else, and this process of reduction and abstraction makes the model obviously much less than the original object” (4), leading me to wonder whether there’s value in the network model approach in folklore studies; is the network model appropriate for exploring and ideally illustrating the use of a fairy tale character despite and/or because of its specific placement in plot? What are the potential benefits of seeing folklore from a network perspective than from, say, the database of the ATU? For my boot camp, I decided to explore the potential of network diagrams with Once Upon A Time, which is of particular interest because of its constant allusions to Disney fairy tale films, and the dense network of fairy tale themes this move invokes.

In my first diagram, I attempted a simple and somewhat failed attempt to illustrate how Once Upon A Time combines two previously independent networks, or tales (fig. 1) – in this case, the previously independent tales of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast.” However, this diagram only indicates that two tales overlap, and provides no supplementary qualifications for this relationship. After experimentation, I ended up with a Venn diagram to represent my network (fig. 2). This Venn diagram attempts, like Moretti, to “make visible specific ‘regions’ within the plot as a whole; subsystems, that share some significant property” (4). Venn diagrams comparatively evaluate data, which I use to demonstrate the “regions” of plot (that of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast”) ABC constructs in Once Upon A Time’s narrative by sharing significant tale attributes (e.g. character associations).

Thus “Rumpelstiltskin” is also the Beast from “Beauty and the Beast.” But this narrative is further complicated with ABC’s explicit allusions to Disney’s version of Beauty, Belle, who shares the same name and attire as ABC’s live action version; “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and Once Upon A Time collapse into each other under the umbrella corporation of Disney, owners of ABC since 1996. This Venn diagram ends up illustrating Disney’s corporate ownership of specific tale attributes (Belle) and ABC’s consequent (legal/legitimate) ability to manipulate Disney associations, simultaneously enacting folklore’s transformative gestures as well as corporatized indications of self-reference that actually paradoxically close off the network of folkloric associations in favour of expanding economic investment. In the densest part of the Venn diagram, we have the most convoluted manipulations of the folklore network for the consolidation of corporate ownership through cable network television.

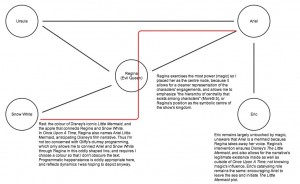

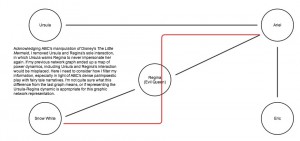

This almost hegemonic assimilation of two or more tales continues and becomes a hallmark trope of Once Upon A Time. My third through fifth diagrams examine “Ariel,” the episode dedicated to “The Little Mermaid,” which unsurprisingly emulates the Disney version by referencing Ursula (unknown to the tale-type prior to Disney), Ariel (once again, Disney specific), and clothing the titular character in the same attire Disney created over a decade ago. In fact, “Ariel” is fascinating precisely because ABC capitalizes on Disney’s copyright ownership and elaborates upon The Little Mermaid while enabling its narrative: while Prince Eric appears in the episode, his knowledge of Ariel is minimal and can actually inform the movie’s catalyzing romantic plot;

prior to Regina’s (the Evil Queen from “Snow White”) impersonation of Ursula, Ariel believes Ursula is only a myth, and thus ostensibly would not have sought the sea witch out in the film if not for the knowledge Once Upon A Time imparts upon her; Regina actually names Ariel Little Mermaid, becoming ABC’s narrative consolidation as well as corporate nod to their parent company. Thus Regina is the centre node of my network diagram, because her character not only fuels the narrative with her machinations, but visually marks the centripetal structure of the corporate networks at work.

“No interaction is crucial in itself. But taken together, they perform an essential reconnaissance function: they make sure that the nodes in this region are still communicating: because, with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility” (Moretti 9). This is where suspicion informs my plotting of ABC and Disney networks: no interaction is crucial, but as the removal of Regina makes clear, the Evil Queen’s interactions are in fact crucial to legitimizing the combination of Snow White, the Little Mermaid, and even more tales in Once Upon A Time. The enforcement of Disney’s network through self-references legitimizes these fairy tales as Disney’s property, and “with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility.” Thus, we have the Evil Queen, a tyrannical monarch who colonizes various tales under Disney(‘s)World, a self-enclosed narrative where transformations are only variations of their own copyrighted characters, and the transmission and transmutation of tales have shifted from the public sphere to the privatized corporate one. As much as my first diagram attempted to illustrate two previously closed-off networks opening affiliative possibilities, what my diagrams have made visibly evident is that these networks seem to have become increasingly more (in)corporated.

Works Cited

“Ariel.” Once Upon A Time. ABC. 3 Nov. 2013. Television.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab 2 (May 2011).

The post Boot camp: (In)Corporations of Fairy Tales in ABC’s Once Upon A Time appeared first on &.

]]>