The post Avatar: The Last Airbender: Bending Boundaries between Appreciation, Appropriation, and Adaptation appeared first on &.

]]>Between 2005 and 2008, American-based television network Nickelodeon aired what would become one of the most lauded and commercially successful children’s shows of its time, Avatar: The Last Airbender. At its best, Avatar presents stirring storylines that grapple with the complexities of human relationships in meaningful ways, offering the audience narratives that confront racism (“Book 1-3”), misogyny (“The Warriors of Kyoshi,” “The Waterbending Master,” “The Painted Lady”), classism (“The Swamp”), and ableism (“The Blind Bandit”), while foregrounding redemption (“The Western Air Temple”), forgiveness (“The Southern Raiders”), and the importance of social support systems (“Sozin’s Comet: Part1-4”). Grounding its moral message primarily in the tenets of Buddhism and Hinduism, Avatar encourages children to become peaceful adults who work together to avoid perpetuating erasure or violence against other cultures.

Yet the American television show’s homage to and reliance on eastern and indigenous culture—in everything from its visual aesthetics to the cultural makeup of its invented nations—threatens to push the series into the realm of cultural appropriation. The fraught relationship between North American and Asian culture embedded in the makeup of the show is further complicated when considering the ramifications of M. Night Shyamalan’s film adaptation, The Last Airbender, in which the three protagonists are effectively whitewashed. This probe considers a number of nuances between cultural appropriation and appreciation in an attempt to underscore the fluidity between these categories and interrogate whether culture can be owned—and, if so, by whom.

Book 1: Appropriation

Avatar: The Last Airbender is set in a fictional Asian-inspired world divided into four nations based on the elements of the dominant natural-philosophical theory in Chinese Buddhist literature: the Water Tribes, Earth Kingdom, Fire Nation, and Air Nomads. Populating this world are people who can manipulate the elements of the nation they are born into through a process called “bending,” which is visually stylized after the martial arts T’ai Chi, Hung Gar, Northern Shaolin, and Ba Gua in each respective nation. The story follows a twelve year old boy named Aang—the last surviving airbender after the Fire Nation committed mass genocide against the Air Nomads—who also happens to be the Avatar, a being of heightened spiritual ability whose role is to master all four elements and bring balance to the world. Accompanying him on his adventure are siblings Katara and Sokka, whose dress, hunting practices, and villages in the South Pole borrow heavily from Polynesian and Native American cultures.

Avatar’s visual style is heavily indebted to Japanese anime and the work of artists and studios such as Miyazaki, Gainax, and Shinichiro Watanabe, setting it apart from other cartoons airing on Nickelodeon. The show’s broader eastern aesthetic is equally deliberate. In an interview on Nickelodeon, creators Michael Danter DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko describe the process of creating Avatar as the following:

[W]e wanted to create a mythology that was based on Eastern culture, rather than Western culture. […] we were inspired by Asian mythology, as well as Kung Fu, Yoga, and Eastern Philosophy. […] We read a lot about Buddhism, Daoism, and Chinese history. We also have several consultants who work for the show—a cultural consultant that reviews all the scripts; a Kung Fu consultant who helps choreograph all the bending moves so that they are accurate to the style on which they are based; and a Chinese calligrapher who does all the signs and posters in the show.

DiMartino and Konietzko vacillate between appreciation and appropriation of Asian culture and, at times, even seem suspicious of their own positionality relative to their creation. On the one hand, they engage with the people whose cultures they borrow from in order to build trust and ensure their work is as authentic as possible. As Marcus Boon argues in In Praise of Copying, “copying […] is connected to love” (234), and the creators of Avatar claim they are “just trying to pay homage.” On the other hand, DiMartino and Konietzko do more than pay homage when they appropriate spiritually significant terms: “We chose the word ‘Avatar’ because it is an ancient Hindu word meaning ‘a temporary manifestation of a continuing entity.’” Hindu, Buddhist, Daoist, and Shinto spiritual influences converge and become the religious doctrine of the Avatar world, ignoring the fact that these religions have historically served as a source of social and political divisions between groups.

In “From Appropriation to Subversion,” Peter Kulchyski argues that “[a]ppropriation involves the practice on the part of dominant social groups of deploying cultural texts produced by dominated social groups for their own (elite) interests” (614). Following that definition, Avatar can be considered appropriation par excellence, a franchise that engages both in cultural voyeurism and cultural appropriation in order to create a show that appeals to the exoticization and fetishization of dominated social groups.

“Since ‘culture’ can be characterized as one of the most useful intellectual tools of the twentieth century—slowly coming to replace the nineteenth century concept of ‘race’ as a way of differentiating peoples—it has come to be taken for granted and, to an extraordinary extent, vacated of focus or precision.” (Kulchyski 605)

It is this lack of focus that facilitates appropriation in the name of homage; two American creators cherry pick from various Asian and Indigenous cultures to create a melting pot that blends aspects of real-world nations and erects distinct—if not wholly artificial—boundaries within the cartoon environment. As a result, Avatar presents an ancient world comprised of elements an American is likely to associate with Asia or Indigenous groups—martial arts, Buddhist and Hindu spirituality, food preparation and consumption practices, Chinese calligraphy, etc.—decontextualized from any explicit, specific history or culture. Avatar’s world, no matter how well researched, becomes flattened into a generic representation of Asian-ness, and it is this very flattening that eludes appropriation. With the boundaries so blurred, what can we even argue has been appropriated from individual cultures?

Book 2: Adaptation

When Paramount announced a live action film trilogy adaptation of the much beloved series, fans’ excitement was short lived after it became clear that the movie would whitewash the series. The Last Airbender’s four starring roles were initially all to go to white actors, but, when pop singer Jesse McCartney backed out of the role of villain Zuko due to scheduling conflicts and was replaced by Dev Patel, a whole new issue of representation came to light. In casting a South Asian actor as the villain, The Last Airbender problematically connects darker skin to the corruption of the Fire Nation. Although Avatar is by no means a perfect representation of Asian cultures, The Last Airbender strips the series of its detailed research and replaces complex race relations between the four nations with a world in which the villains are marginalized bodies in opposition to homogenous white heroes.

In an interview with TIME Magazine, Shyamalan takes full ownership of the whitewashing of The Last Airbender, saying, “I could have cast anybody I wanted to. You’re talking to one of the only Asian filmmakers in the world who has complete control.” Shyamalan’s case is that, given his status as Indian-American, casting exclusively white actors to play the heroes of his film cannot possibly be racist because he himself is of South-Asian descent. This defence raises important questions of appropriation: namely, can one appropriate when one comes from an often-appropriated community themselves?

Evolving out of a letter writing campaign on LiveJournal called “Aang Ain’t White,” which protested the movie’s casting decisions came Racebending.com. Informed by the theories articulated in Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble, racebending also makes a clever pun on the abilities of inhabitants of the Avatar world to bend the elements. Whereas Butler’s theory of gender bending refers to the celebratory practice of performing gender against biological sex and cultural expectations, racebending replaces marginalized bodies with white bodies, restricting rather than broadening possibilities. As well, “‘racebending’ can be seen as more than simply changing the race of a character: it is changing the race of characters of color to white for reasons of marketability” (Lopez, qtd. in Gilliland 2.4). Not merely a symptom of neglect or cultural naivety, racebending is a deliberate, strategic erasure of people of color in order to increase capital.

Aang, Katara, Sokka, and Zuko in the animated series, their actors, and their voice actors. Only Zuko, the villain, is consistently represented as a person of color.

But how can one claim the erasure of identity when, to a great extent, the characters in The Last Airbender have always been white? While they are visually depicted as Inuit and East-Asian and drawn in an anime style, Aang, Katara, and Sokka were created by two white men and voiced by white people. Indeed the villain-turned-antihero Zuko is the only one of the four to have been voiced by an Asian-American in the original series. The fact that boycotters of The Last Airbender were a) by and large not Asian or of Asian descent and b) seldom considered the fact that the majority of the original voice actors were also Caucasian suggests that perhaps fans are more attached to the idea of Indigenous- and Asian-ness the American creators present in Avatar than with the individual cultures themselves. After all, the show attempts to provide a model for doing Eastern cultural appropriation right. Fan outcry that The Last Airbender is “ruining” Avatar directs the gaze instead towards the endemic problem in Hollywood where Asian actors, writers, and directors are replaced with white actors, writers, and directors who presume to tell their stories. In my previous probe on appropriation of Coast-Salish cultural objects, I briefly addressed the ways in which dominant culture insists on enforcing their own understanding of what aspects of a given marginalized culture is authentic. In this case, Avatar and the resulting resistance to the casting of The Last Airbender use authenticity as a way to legitimize the cultural appropriation inherent in the original television series.

Book 3: Appreciation

Avatar and The Last Airbender do not exist solely on a screen, but are part of a larger system of cultural production. As Frederic Jameson notes, “What has happened is that aesthetic production today has become integrated into commodity production generally” (qtd in Kulchyski 610). Between Avatar and its spiritual successor, The Legend of Korra, the franchise has built an immense commodity culture, consisting of comic books, video games, Lego, jewelry, clothing, and cosplay, raising questions about appropriation grounded in fans’ reactionary behaviors. For instance, is wearing orange robes appropriative if it is accompanied by blue arrow tattoos as a direct homage to an American cartoon at a comic book convention? Is it appropriative to write fanfic grounded in Asian history and mythology in order to engage in world-building in the Avatar universe?

To conclude this probe, I want to address Marcus Boon’s comment that, although today’s prevalent appropriation does not obey the laws of cultural exchange, “this doesn’t mean it’s used solely by the privileged or powerful on the marginalized and powerless, since it’s also employed by the marginalized and powerless” (231). Two weeks ago, Nigerian illustrator and comic book artist Marcus Williams released images from his Avatar fan-fiction, Avatar: The Legend of Abioye. Set one hundred years after Korra, the adaptation reimagines the characters as Nigerian, and encourages us to think about the effects of yet another type of racebending: is it appropriative for one dominated culture to depict themselves in the space of another? Or is Williams reclaiming Avatar for the marginalized after Hollywood’s instatement of white hegemony? By setting his story a century later, Williams refrains from appropriating and erasing the characters who are clearly stylized as Asian and Indigenous and tactfully allows his new Yoruba benders Iya, Ikenna, and Ballogun to (co)exist in the Avatar universe. As fanfiction, Avatar: The Legend of Abioye arguably presents a true attempt at appreciation without appropriation.

Works Cited

Avatar: The Last Airbender. Written by Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko, directed by Lauren MacMullan, Nickelodeon Animation, 2005-2008.

Boon, Marcus. “Copying as Appropriation.” In Praise of Copying. Harvard University Press, 2010, pp. 204-37.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Avatar: The Last Airbender answered by the creators, Mike & Bryan!” Nicksplat.com Nickelodeon, 12 Oct. 2005.http://web.archive.org/web/20071217111256/http:/www.nicksplat.com/Whatsup/200510/12000135.html. Accessed 4 Nov 2016.

Gilliland, Elizabeth. “Racebending Fandoms and Digital Futurism.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol 22, 2016, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/702/651. Accessed 4 Nov 2016.

Konietzko, Bryan, & Michael Danter DiMartino. Avatar, the Last Airbender: The art of the animated series. Dark Horse Comics, 2010.

Kulchyski, Peter. “From Appropriation to Subversion: Aboriginal Cultural Production in the Age of Postmodernism.” American Indian Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 4, 1997, pp. 605-620. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1185715. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

The Last Airbender. Directed by M. Night Shyamalan, performances by Noah Ringer, Nicola Peltz, Jackson Rathbone, and Dev Patel, Nickelodeon Movies and Paramount Pictures, 2010.

Shyamalan, M. Night. “10 Questions for M. Night Shayamalan.” TIME Magazine, 12 July 2010. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2001008,00.html. Accessed 4 Nov 2016.

The post Avatar: The Last Airbender: Bending Boundaries between Appreciation, Appropriation, and Adaptation appeared first on &.

]]>The post “This Web Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us”: On Web Sheriff and Anti-Piracy as a Business Force appeared first on &.

]]>I can still remember the pang of disappointment that accompanied the email. GirlAttorneys – or, in the du jour stylization of the time, GIRLATTORNEYS – a music blog that I had run with a couple of friends for close to a year, had been permanently shutdown by Blogger for one too many DMCA takedown notices. This was around the tail end of (what I have seen music forum obsessives recall anecdotally as) the “golden age” of music blogging, a post-Napster period that saw a perhaps unprecedented sharing of obscure and out of print music via the proliferation of blogspot domains – such as Experimental, Etc., Mutant Sounds, and Ghost-Capital – and the relative ease of use of digital file storage “cyberlocker” services like Megaupload, RapidShare, and MediaFire.

I had written some longform pieces for the site, but, by and large, we acted as other lower-level music blogs did at the time, posting links to recently-leaked and older favourite albums hosted on MediaFire. The DMCA takedowns that were our undoing came in quick succession in May 2010 for The New Pornographers’ Together and LCD Soundsystem’s This Is Happening, both hotly anticipated albums for that quarter in the independent music community, and that I had instantly posted in hopes of luring traffic to the site, and, hopefully, to my other turgid musings on 80s R.E.M.

The entity that served the notices to Blogger and took us down was the aptly named Web Sheriff, a still-functioning private content-policing service headed by longtime intellectual property lawyer John Giacobbi. Web Sheriff specializes in a “unique and successful combination of anti-piracy services, viral marketing and mass traffic re-direction [that] has been proven to dramatically increase sales and drive on-line traffic to official sites and promotions in huge numbers” (“Services”), and, in the years following my specific takedown, increasingly became known for its gentler approach to enforcement[1], aiming to differentiate between various forms of piracy – “ardent fans who can’t wait for an official release; techno-geeks who are out to show they can beat the system; and hard-core music pirates” (Lewis) – and treat them accordingly. Although, I should note, nothing about GirlAttorneys’ takedown felt indicative of a “fan-friendly approach” (Bruno), instead falling more in line with a certain sentiment expressed on the company’s “About Us” page in a (laughably simplistic?) metaphor: “this [garden analogy] is a very accurate analogy and many are the times when we’ve been called in and asked to help transform a ‘netscape’ from weeds to roses … and just as this is possible with real gardens, so too is it possible on the internet” (“About Us”).

The somewhat protracted point that I am leading to here is that there is a business of/to anti-piracy, and it is one that frequently isn’t acknowledged in our popular folk conceptualizations of piracy’s political economy. As Ramon Lobato and Julian Thomas argue, in their article, “The Business of Anti-Piracy: New Zones of Enterprise in the Copyright Wars,” this is largely a result of the narratives around piracy that we receive – and, at this point, inherit – from industry/trade group anti-piracy rhetoric. As Lobato and Thomas state, “[a] key strategy of content industry groups during their long war on piracy has been to associate copyright infringement with lost revenue for artists, producers, and media businesses” (606), which leads to, in turn, an understanding founded on “the model of a zero-sum economic redistribution between two camps—producers and pirates—with the latter cannibalizing the revenues of the former” (606).

As a now humorous example of this rhetoric at play, consider the Software Publishers Association’s 1992 anti-software-piracy video “Don’t Copy That Floppy.” In the video, MC d/p (short for Disc Protector), a “rapping, human version of DRM” (Crezo), interrupts two children in the process of copying a floppy disc game, and proceeds to lecture them on the computer programming industry’s viability and copyright law before throwing over “to some of the team” – a game designer, programming director, and senior programmer – who further explain the benefits of legally purchasing software while also giving a human face to those whose livelihood is harmed even “if [you] make a copy of this science program just to use at home” (“Don’t Copy That Floppy” 6:17-20). Although this example is dated at this point, it is worth reflecting on how this simplistic formulation still operates in contemporary contexts in ways that prove to be deeply unconstructive when attempting to grasp the intricacies of modern piracy economics.

Adrian Johns, in “Piracy As a Business Force,” urges us to see a through-line between the founding pirate radio broadcasters of 1960s Britain and modern-day bit-torrent piracy. In doing so, Johns proposes a different genealogy, as he says, “[t]he appropriate inspirations become not Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog, but Friedrich Hayek and – especially – Ronald Coase and their assaults on public media” (46). According to Johns’ research, “[Oliver] Smedley’s cohort saw in [pirate radio] the possibility for a thoroughgoing challenge to an entire political and economic system. Their Project Atlanta would begin by undermining information monopolies. Piracy for them was to be first a business force, then a cultural force, and finally a political force” (58). For the pirate broadcasters that Johns studied, then, we can say that piracy had a tremendous generative potential, as he demonstrates through careful examination of Institute of Economic Affairs tracts. Citing the examples of Allen Lane and John Bloom, the IEA tracts convey that, within this libertarian ideological framework, supposed “piratic” activity was conceived of as essentially unwanted innovation that challenges established monopoly interests.

Interestingly, what Lobato and Thomas explore in their work is the generative potential of anti-piracy as a business force:

a generative logic is at work in contemporary IP economies: piracy produces new anti-piracy enterprise, which in turn produces new informal workarounds for pirates, which generate new anti-circumvention responses, and so on. The pattern here is not leakage but dispersal, with commercial opportunities created in both the legal and extralegal spheres, leading to the consolidation of diverse and rapidly expanding lines of business around IP enforcement, policing, research, and technological prevention. (Lobato and Thomas 607 emphasis added)

As a result of this generative logic, in the contemporary digital context, perhaps we could say that MC Disc Protector has been able to incorporate and diversify, graduating from the spatial confines of a 1992 classroom desktop to the anarchic world of the web. Lobato and Thomas go on to examine what they term the “Four Sectors of the Anti-Piracy Industries” (610) – technological prevention, revenue capture, knowledge generation, and policing and enforcement – with the caveat that each industry sector may do work that is used by or that informs another. Each sector sees the problem of piracy differently, may offer different services/products to different markets, and have a different strategic aim. Web Sheriff figures in their typology – falling under the sectors of knowledge generation and policing and enforcement – because, as of 2012, the company was involved in P2P traffic measurement and in generating takedown notices.

Lobato and Thomas’ “Four Sectors of the Anti-Piracy Industries 1995–2010” table from “The Business of Anti-Piracy:

New Zones of Enterprise in the Copyright Wars,” p. 610.

They then map a “formal/informal” economic differentiation onto the four sectors of industry, where the creative content industries are a level of largely formal production and distribution, the piratic industries are a level above and are informal, and the anti-piratic enterprises are, again, a level above and are largely formal (616). Intuitively, the (informal) piratic industries are entirely dependent on the formal creative content industries, and, analogously, the (formal) anti-piratic enterprises are entirely dependent on those (informal) piratic industries. Each anti-piratic industry sector has a different “rationale/formalizing strategy” for formalizing these informal piratic activities. For example, the revenue capture sector aims “[t]o create advertising markets from infringing traffic,” while the policing and enforcement sector instead has the objective of “creat[ing] law-abiding citizen-consumers to sustain returns on investment for content producers” (617). Lobato and Thomas’ model, therefore, more accurately reflects the complicated flows of capital in the digital economy in a way that helps us move away from overly reductive models predicated on the “zero-sum economic redistribution between two camps [producers and pirates]” (606). They summarize their approach by emphasizing its primary focus on the form of content/commodity as a basic unit of investigation: “We propose that another way of thinking about the economics of piracy is to begin with certain media products and practices and then track all the different kinds of income-generating activities that open up around them, as they cross back and forth between the formal and informal zones” (617).

What do we take from all of this? Piracy, itself, can be conceived of as a business force, in both the historical sense offered by Johns’ linking it to the IEA, and in terms of its contemporary economics, such as those treated in the Social Science Research Council’s influential Media Piracy in Emerging Economies. In addition, though, as Lobato and Thomas document, anti-piracy has also become a significant economic force with its own disparate sectors and strategic aims, often ones that may diverge from traditional litigation practices into grey areas where “[a]nti-piracy litigation is … not completely congruent with anti-piracy deterrence” (620), such as in their example of the practice of en masse speculative invoicing of “infringement” (618-20). What does this entail for us if we choose to study piracy? How might it influence or complicate research methodologies in ways that cause us to scrutinize information more closely? For example, now that we know that, in addition to industry groups like the Motion Picture Association of America or the Recording Industry Association of America, there may be other private corporate players who have a profit-motive interest in “knowledge generation” as it relates to public discourse around piracy, how do we remain vigilant in our scholarship regarding the information that we gather and use?

As Lobato and Thomas assert in their concluding section, “[r]ather than seeing the piracy wars as a David and Goliath battle between consumers and corporations, as per the liberal copyright reform script, or as the final crisis of informational capitalism, we also need to see them as driven by ad hoc commercial practice” (621). In following Lobato and Thomas I feel that any responsible scholarship on contemporary piracy should take into account this practice and its effects, and I think that, in doing so, we can continue to raise provocative questions about piratic activities and their regulation while remaining grounded in a clearer understanding of the political economy that underlies them.

[1] As a reflection of this approach, Helienne Lindvall makes mention in The Guardian of Web Sheriff opening a thread (that ran to 18 pages) on brainkiller.it, an unofficial fan forum for the electronic producer The Prodigy, back in 2009. Sadly, only a lone page of this thread remains cached on the Wayback Machine, but it still provides a fascinating glimpse of the “Sheriffian” ethos in action. The featured header image for this article is a screenshot of a Web Sheriff post from the thread.

Works Cited

Bruno, Anthony. “New Sheriff In Town: Anti-Piracy Company’s Shifting Tactics Reflect Market’s Pivot From Enforcement To Engagement.” Billboard, 9 July 2011: 8.

Crezo, Adrienne. “‘Don’t Copy That Floppy’: The Best Bad PSA Ever Is a Rap From ’92.” Mental Floss, 2 May 2014. http://mentalfloss.com/article/12561/dont-copy-floppy-best-bad-psa-ever-rap-92. Accessed 25 Oct. 2016.

Johns, Adrian. “Piracy As A Business Force.” Culture Machine 10 (2009): 44-63.

Lewis, Randy. “Piracy watchdog’s mild bite: Web Sheriff prefers to persuade, not prosecute, music fans.” Los-Angeles Times, 9 June 2011. http://articles.latimes.com/2011/jun/09/entertainment/la-et-web-sheriff-20110609. Accessed 25 Oct. 2016.

Lobato, Ramon and Julian Thomas. “The Business of Anti-Piracy: New Zones of Enterprise in the Copyright Wars.” International Journal of Communication, 6 (2012): 606-25.

Software & Information Industry Association. “Don’t Copy That Floppy.” YouTube, uploaded by SIIA Anti-Piracy, 2 Apr. 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkdzy9bWW3E. Accessed 25 Oct. 2016.

Web Sheriff. “About Us.” Web Sheriff: Creative Protection, 2016. http://www.websheriff.com/about-us/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2016.

—. “Services.” Web Sheriff: Creative Protection, 2016. http://www.websheriff.com/services/. Accessed 25 October 2016.

The post “This Web Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us”: On Web Sheriff and Anti-Piracy as a Business Force appeared first on &.

]]>The post Knitpicking over Ownership: Cultural Heritage Ethics and the Coast Salish Cowichan Sweater appeared first on &.

]]>Aided by the advent of the internet, knitting has enjoyed a resurgence over the past two decades, particularly among younger generations drawn to the craft as a stress-relieving and potentially eco-friendly pastime. The growing number of knitting blogs and the popularity of the online platform Ravelry allows patterns and objects to circulate on- and off-line with ease, generating both economic and cultural capital for a number of craftspeople and communities.

Like recipes and similar artisanal practices, knitting patterns and knitted objects frustrate easy classification with respect to their position as intellectual property under the current regime of copyright law. As a tangible medium, the paper or PDF pattern is covered by copyright as an image, but the process outlined in either the visual knitting charts or the technical descriptions—which themselves often repeat a vocabulary of knitting terms understood by a particular interpretive community—is not eligible for protection under Canadian copyright (Murray & Trosow 171). Although Susan Belyea addresses glassmaking in particular when she states, “we’re all working with the same tools” (qtd in Murray & Trosow 170), the claim to technical universality extends to numerous artisanal practices, including knitting, which, as a process, is comprised of merely two fundamental stitches, the knit and the purl.

As an object, it is difficult to even begin to untangle the question of who owns a piece of knitwear, given that it is indebted to a number of interwoven components that extend beyond the aesthetics produced by the pattern, such as fiber content, dye lot, needle size, product size, knitting technique, seaming technique, and gauge among other elements. A knitter may look at an existing scarf pattern that specifically calls for bulky weight yarn and adapt it to whatever they have on hand. Although this new scarf is indebted to the original bulky scarf, it is fundamentally its own object and, unless this new user re-uploads the original pattern with notes scrawled over it in pencil, no copyright infringement has occurred.

While such a system greatly benefits craftspeople who “envision their artistic practice in terms of sharing and giving” (Murray & Trosow 168), it produces a climate wherein cultural and aesthetic appropriation—though not explicitly sanctioned—is not prevented or regulated by copyright legislation. Overwhelmingly at risk of cultural appropriation under Canada’s current system are First Peoples, whose words, imagery, and patterns have long been defined and subsequently appropriated by the dominant colonial culture, which has “negative impacts on the health, wellbeing and capacity for economic self-sustenance of Aboriginal peoples” (Udy). This probe examines the fraught relationship between an influence-sharing craft community and the ethics of appropriation of cultural heritage through a study of Coast Salish Cowichan sweaters.

A Brief History of Coast Salish Knitting

The Coast Salish are a group of ethnically and linguistically related First Peoples along the Pacific Northwest coast, living in what Canadian colonizers call British Columbia, as well as the states of Washington and Oregon. In an article titled “The Coast Salish Knitters and the Cowichan Sweater: An Event of National Historic Significance,” Marianne P. Stopp provides a detailed account of the history of Coast Salish knitting, the most significant moments of which I summarize in the following paragraphs.

Long before European colonization, Coast Salish women wove mountain goat hair, dog hair, and plant fibres into valuable trade commodities, such as ceremonial blankets. Weaving was achieved by twisting spun fiber strands into each other using fingers. Until the 1970s, all wool was prepared by hand, a process that took seven months to complete, beginning with the shearing of the sheep and followed by numerous washings, dryings, and spinnings in order to make the yarn unusually durable, weatherproof, and warm.

In the 1860s, the Coast Salish women were introduced to two-needle and multiple-needle knitting by the sisters of the Catholic missions. Through a process of unravelling settler sweaters and copying their construction through trial and error, the Coast Salish reproduced the Fair-Isle style of knitting presented to them. Retaining their unique wool preparation process, the Coast Salish paired aspects of settler knitting with common motifs and symbols often found in their wordworking and basketweaving.

The entwining of traditional Coast Salish wool spinning with European knitting styles and techniques resulted in a distinct sweater that became known as the Cowichan, and demand for the quality garment was high. Although profit margins for the knitters were minimal, it nevertheless provided Coast Salish women with opportunities for economic stability:

Women were introduced to wool-working by the time they were seven or eight years old. This practice was borne partly out of economic necessity, but it also aligned with traditional Coast Salish practices of training young girls to become skilled textile producers and to live productive lives. (Stopp 15)

In a detailed study of Coast Salish knitting, Sylvia Olsen notes that, when asked how a family retained economic stability until the 1980s, most Coast Salish people would answer, “My mother knit” (7). Knitting was not only a way to make ends meet but also an important avenue for women’s agency.

Historic Cases of Appropriation

The 2010 Vancouver Olympics were rife with instances of appropriation of First Peoples’ culture. The games not only appropriated and misused depictions of sacred knowledge, such as the inukshuk, but also “commercialized products based on traditional knowledge or expressions of culture, without sharing the profits with the community from which such knowledge originated” (Udy). When the Hudson’s Bay Company revealed their Olympic clothing line, they were critiqued for appropriating the Cowichan aesthetic while outsourcing production to a third party who used cheap materials and machine-based knitting. To add insult to injury, the Bay then trademarked this inauthentic design.

The Bay is far from being the only group to engage in appropriation of the Cowichan sweater: Roots, in collaboration with Mary Maxim and Ralph Lauren have also released lines of sweaters heavily inspired by Coast Salish design, and popular yarn brands, such as Patons and Pierrot yarns, offer patterns for Cowichan sweaters that can be downloaded for free or for a minimal fee in order to entice knitters to purchase their particular yarn.

Moreover, a Ravelry search returns 202 patterns that define themselves as Cowichan or Cowichan-inspired, the majority of which are not posted by Coast Salish users. These patters serve a particular economic function related to cultural capital in the interpretive community of knitters who find their patterns online. If a knitter is introduced to a designer through free patterns that are easy to follow and yield promising results, the consumer is likely to purchase their paid patterns as well.

Online knitting platform Ravelry yields 202 results for the search term “Cowichan.”

The ease of access of such patterns allows thousands of knitters not only to begin making Cowichan sweaters for themselves but also for others in either the gift economy of craftwork or for profit—depending on the pattern’s license and /or whether knitters choose to adhere to such a legally unenforceable license. Using cheap materials from the local Michael’s rather than hand processing the yarn themselves, knitters saturate the market with appropriative knockoffs that are cheaper to produce and cheaper to ship to consumers.

Unravelling Ethical Knots

The rights of peoples with respect to cultural heritage goods pose new and pressing challenges in terms of balancing the exercise of intellectual properties with individual freedoms of creativity, collective rights, and international human rights obligations. (Coombe & Aylwin 201)

Frustratingly, nothing in the appropriative practices discussed above is actually illegal under copyright law. From a perspective grounded solely in intellectual property rights, neither the Bay nor the individual users on Ravelry posting Cowichan-inspired sweaters have transgressed any obvious legal lines.

In an article on Indigenous Cultural Heritage, George Nicolas considers how cultural “borrowings” (214) are justified as “an appreciation of the great ‘vanished race’” (214), even though their cultural heritage and expressions are still critically important in their extant culture. On the other side of the coin is dominant culture’s insistence on enforcing their own understanding of what aspects of a given marginalized people’s culture is authentic. The popularity of Cowichan sweaters led non-native consumers to expect a certain aesthetic associated with the garment, namely that they would be made with undyed wool. When the Coast Salish women were introduced to brightly colored cotton and acrylic yarn and used this yarn in their sweaters, the designs did not sell because the sweater no longer conformed to the aesthetic expectation imposed upon the Coast Salish peoples by the settler consumer. In other words, it upset the colonizer’s notion of a distinct “Native brand.”

Of course, the obvious element undermining accusations of Western cultural appropriation of First Peoples’ craftwork that this probe has so far danced around is the fact that cultural productions are constantly being inspired and influenced by what came before, particularly in the knitting community where patterns are continuously being exchanged, modified, re-exchanged, and re-modified. The Coast Salish women adapted the settlers’ Fair Isle knitting style into the Cowichan sweater through a process of copying, and introduced their wool and spiritual symbols into an existing process. By the same logic that reproductions of the Cowichan sweater can be called appropriative, the Coast Salish can, theoretically, be accused of appropriating an existing design themselves. The prevailing attitude that knitting patterns and techniques cannot be owned is, paradoxically, that which legitimizes Coast Salish knitting as a unique variation on the craft even as it also legitimizes reproductions.

Nevertheless, “cultural heritage is the result of a dynamic, expressive, and productive practice of dialogue,” argues Rosemary Coombe and Nicole Aylwin (203). The difference therefore, between Coast Salish development of the Cowichan sweater and the Bay’s appropriation of the product is that the former were engaged in a process of creating through dialogue—a non-consensual dialogue, I might add, whereby settlers “educated” Coast Salish women in catholic missions. Rather that present Fair-Isle knitting right back to the colonizer, the Coast Salish women wove their own pre-existing culture into the designs. Conversely, the Bay branded their sweaters as being Cowichan when, in fact, it neglected much of the processes which make Cowichan sweaters distinctive—that is to say, the fact that the sweaters are handmade and one of a kind.

Face Of Native is a small indigenous business that produces and ships authentic Coast Salish goods worldwide.

Moreover, the Cowichan sweater is more than just a knit object. As Nicholas argues, “many Indigenous peoples perceive their world as one in which material objects are more than just things, and in which ancestral spirits are part of this existence, rather than of some other realm” (216). The fibre production that was an important component of the original Cowichan sweaters was part of the fabric of Coast Salish spirituality: “The action of spinning the wool into yarn is presumed to have held transformational elements [and] goat hair and goat hair blankets were central to spirit quest dances” (Stopp 13). By calling a sweater produced by overseas machinery a Cowichan sweater, the Bay fails to account for the deeply spiritual processes involved in the authentic garments’ production. It also fails to acknowledge the ways in which, as previously mentioned, the sweater held a central place in the Coast Salish economy. To call a knit object Cowichan is therefore to imbue it with historical, cultural, and economic significance unique to Coast Salish heritage.

Finally, for close to a century, the “Indian Act” made it illegal for First Peoples to practice their traditions in an effort to assimilate the First Peoples to colonial culture (Udy). Forced into residential schools and subject to assimilative policies, knitting the Cowichan sweater was a subversive act; although colonial consumers implicitly sanctioned the practice through their continuous purchase and fetishization of the sweater, the knitting practice—imbued with traditional and spiritual significance—was itself illegal, and thus the sweater’s continual production a refusal to be silenced.

It is a difficult thing to disentangle the ethics of appropriation when it comes to something as unregulated by legislature as knitting patterns and knitted objects, and thinking about this quandary likely raises more questions than answers: As descendants of the colonizer, what are the ethics of wearing a Cowichan sweater? What if it was purchased from a Coast Salish artisan? What about knitting a Cowichan sweater while using a pattern purchased by someone of Coast Salish heritage? Copyright law fails to provide an answer that meaningfully addresses the cultural history buried beneath these questions.

Cultural oppression and racism against the Coast Salish and other First Peoples are not merely a stain on Canadian history, but an ongoing issue that continues to have a negative impact on these communities. It is therefore vital that craftspeople and consumers of hand-crafted objects remain vigilant over their own practices and refuse to contribute to the ongoing disenfranchisement of these communities by claiming ownership over cultural property they have no claim to.

Resources exist for those who wish to buy an authentic Cowichan sweater and ensure that the economic and cultural capital is awarded to the right people: Cowichantribes makes accessible the contact information of numerous Coast Salish craftspeople, and Face of Native, a small Indigenous business based in British Columbia, ships high quality authentic Coast Salish goods worldwide, while ensuring that artisans are paid fairly for their work.

Works Cited

Coombe, Rosemary and Nicole Aylwin. “The Evolution Of Cultural Heritage Ethics Via Human Rights Norms.” Dynamic Fair Dealing: Creating Canadian Culture Online. Ed. Rosemary J. Coombe, Darren Wershler, and Martin Zeilinger. University of Toronto, 2014. 201-12.

Murray, Laura and Samuel Trosow. Canadian Copyright: A Citizen’s Guide. 2nd ed., Between the lines, 2013.

Nicholas, George. “Indigenous Cultural Heritage in the Age of Technological Reproducibility: Towards a Postcolonial Ethic of the Public Domain.” Dynamic Fair Dealing: Creating Canadian Culture Online. Ed. Rosemary J. Coombe, Darren Wershler, and Martin Zeilinger. University of Toronto, 2014. 213-24.

Olsen, Sylvia. “‘We Indians Were Sure Hard Workers’: A History of Coast Salish Wool Working.” MA thesis, University of Victoria, 1998. University of Victoria Libraries, http://hdl.handle.net/1828/1340. Accessed 17 Oct. 2016.

Ravelry. 2008. ravelry.com. Accessed 17 Oct. 2016.

Stopp, Marianne P. “The Coast Salish Knitters and the Cowichan Sweater: An Event of National Historic Significance.” Material Culture Review, vol. 76, Fall, 2012, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/21406/24805. Accessed 17 Oct. 2016.

Udy, Vanessa. “The Appropriation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage: Examining the Uses and Pitfalls of the Canadian Intellectual Property Regime.” Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage: Theory, Practice, Policy, Ethics, 19 Nov. 2015. http://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/outputs/blog/canadian-intellectual-property-regime/ Accessed 17 Oct. 2016.

The post Knitpicking over Ownership: Cultural Heritage Ethics and the Coast Salish Cowichan Sweater appeared first on &.

]]>The post Other People’s Preserves: The Citation Economies of a Canning Blog appeared first on &.

]]>Unlike most methods of preparing and cooking food, preserving — the practice of canning, pickling, fermenting and drying food — allows for the long-term storage seasonal produce. This temporal dimension specific to preserving has its roots in “historical” practice: these processing methods pre-date the widespread availability of refrigeration technologies, agro-industrial supply chains, and the perpetual harvest of modern supermarkets. The practice relies on biological and thermodynamic processes to stabilize perishable food. As such, while recipes for jams, jellies, pickles and chutneys may vary in terms of their ingredients and flavor profile, processing methods remain consistent: high sugar content for preserves, a low pH for pickles; processing in a hot water bath or pressure cooker; and a good seal. To a certain extent, these recipes change little over time and prove resistant to changing culinary tastes. At the same time, changing USDA food safety regulations and technological innovation (like pressure cookers and the Kerr canning ring) drive republication. The favored guide, the Ball Blue Book Guide to Preserving was first published in 1909 and is currently on its 37th edition.

As a descriptive and instructional form of writing, recipes pose a particular problem in terms of intellectual property vis-à-vis their relationship to real objects. Due to their short length and shared techniques, recipes tend to repeat formal characteristics and whole segments of text. In practice, any deviation from an existing recipe that results in a new object can be claimed as a new recipe. Apple cider vinegar will be substituted for white vinegar in pickles or honey for refined sugar in jams. Two recipes will be combined to create a new variation on the iconic red pepper jelly. A French compote recipe will be updated to American food safety standards. For food blogs and online recipe caches, this issue is compounded by the medium’s lack of fixation. Ostensibly, the blogging platform serves as the “tangible medium” described by copyright’s fixation requirement (Murray & Trosow 42), however the shifting position or that of a blog entry on an infinitely scrolling page or of a blog in a search index confers a sense of impermanence on these works. At the very least, this impermanence impedes a user’s ability to locate and exploit the entry over time. To compensate, canning blogs operate within a citation economy where authors routinely link a recipe with previous entries. This practice reveals both a recipe’s genealogy and a network of recipe producers.

“Internet links are one endless chain of footnotes, only handier. Blogs invite their readers to trace back through their sources like any good academic historian.” (Murray 177-78)

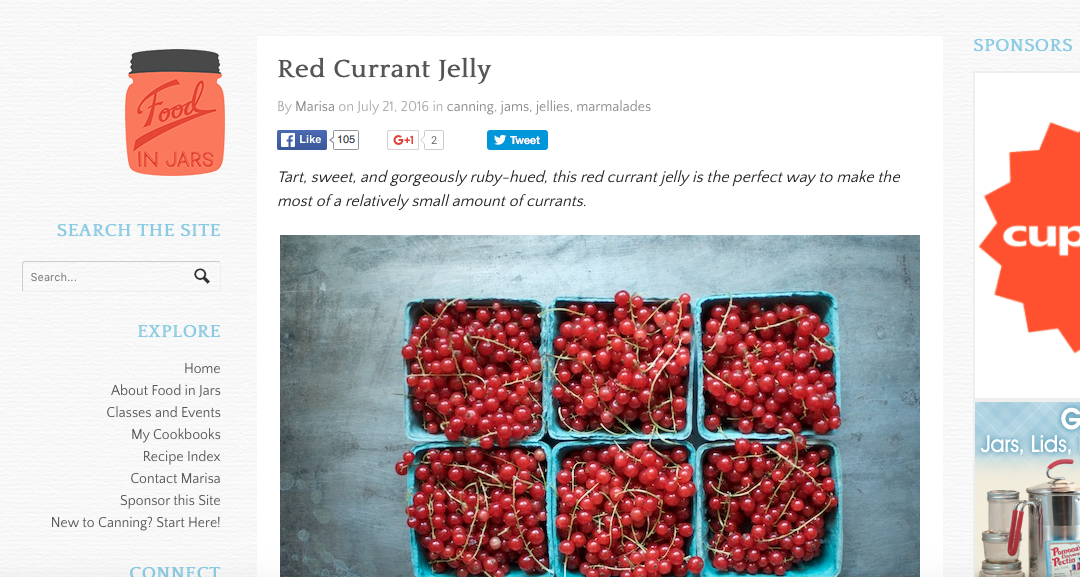

Consider the linking practices of a popular canning blog, Food in Jars, run by Marisa McClellan. In her Red Currant Jelly recipe, McClellan refers to a published recipe book, Pam Corbin’s The River Cottage Preserves, as a source for specialized knowledge for processing hard-to-find fruit in North America, in this case the red currant. As a published author of several canning books, McClellan uses links in her recipes to refer readers to other equally authoritative sources or to similar recipes she has published on other platforms (such as the recipe for Spicy Peach Barbecue Sauce on Ball’s canning blog, Freshly Preserved Ideas, or the Garlic Dill Refrigerate Pickles tutorial and recipe she wrote for The Kitchn).

In addition to these references, McClellan also provides her readers with a “weekly roundup” of links: new recipes, affiliate links, and canning inspiration. These lists consist of 10-12 recipes found on other canning blogs, lifestyle blogs, or a publisher’s site; or recipes digitally reproduced from print collections. Occasionally, one of these links will come from a posted recipe in which McClellan is referenced by an author, as is the case here and here.

In her chapter on the gaps and overlaps between citation economies and copyright law, Laura Murray characterizes the citation system used by bloggers as a “reputation economy” in which cultural capital is bestowed on identified “sources” through hypertext links (174). Cultural capital, rather than economic capital as in the copyright system, because attribution relies on free, cited circulation and “does not result in direct payment” for the source (174). In this sense, citation systems intersect and interact with market systems but function independently of intellectual property law (174-75). Her use of blogging and hypertext practices as examples of a citation economy is interesting considering how monetized blogging has become. If attribution does not directly result in monetary compensation for the original source, monetized linking practices can directly influence the income of the blogger, as well as benefit their reputation.

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) theory — the set of rules through which bloggers “understand” the algorithms running search engines and could affect their placement on search results — dictates that an website’s influence and authoritative value is governed in part through the number of third-party websites which link back to the site. Whether or not this is the case, this aspect of SEO has shaped the way in which blogging communities relate to one another — driving a “gifting” or exchange economy. In this economy, bloggers are encouraged to write guest posts to other sites and link to peer blogs through profile pieces and weekly link round-ups to encourage these blogs to “link back.” Furthermore, professional bloggers have monetized these peer-to-peer relationships: guest posting has turned to paid ambassadorships or publicity; links and recommendations have turned into affiliate links, wherein the author is remunerated for reader click-throughs and purchases; and blog posts are interspersed with native advertising and sponsored content.

Effectively, within this “reputation economy,” it becomes impossible to discuss a citation economy divorced or extracted from a market economy as Murray argues. The monetization of blog citations moves beyond the co-opting of a citee’s authority by the citer and highlights the paradox of Bensman’s 1988 essay on citation economies: whether one considers the ideological or economic context a factor in the construction of citation networks, there is no unbiased perspective from which to ascertain their possible objectivity through our own implication in these systems. (Or, in his words: “Whether a theme is proven or disproven by a self-conscious distortion of documents referred to in a text is not merely a matter of technical proficiency, but one which strikes at the heart of the entire scholarly enterprise. But when ideologies are involved, judgment as to what constitutes an accurate representation of the evidence and of particular sources, is itself conditioned by the ideologies and ideological causes which may lie outside of scholarly proficiency and even self-conscious dishonesty” (449).)

At the heart of this concern, is the relationship between author and the field of production — and its expression through citation networks. What troubles Bensman on a practical level is an author’s ability, through these citation networks, to misrepresent a field of knowledge through “elitist” references or “deviant” citations. Underlying this concern is the troubling realization that a field of knowledge is a virtual construction produced by citation practices — the “social construction of reality” of a scholarly field.

“Yet because of the range of choices available to the citer (and the ongoing structure of citing behavior) this input [citation] can determine, if only in part, the output, the continuously emerging structure and culture of a field, also seen as a social reality.” (443-44)

Bensman’s article is an interpretive declension of the relationship between an individual author and a field of knowledge through the lens of citation practices. For him, the vertical or horizontal stratification of a field and legitimation is not solely produced by citations, but by ideological factors and personal motivations in a biased network of shifting relationships.

Interestingly, Bensman does not use the term “network” to describe the “input” and “output” of citations (nor is he gesturing towards actor-network theory in the way that I’m implying), but he does apply the term to the “social networks that exist in a field,” in the same sense as “networking” that in his understanding functions similarly to the “academic structures” or “‘party’ lines” that affect an author’s citation economy. Writing thirty years later, Murray draws the comparison between academic citation and networked hyperlinks in her essay: “Internet links are one endless chain of footnotes, only handier” (Murray 2008 177). What does it mean, then, to say that citation economies function conceptually as linked networks in academic writing?

My interest in discussing the citation economies of a canning blog has been to consider — along the lines of Bensman’s problematization of the relationship between individual author and field of knowledge — how the remediated relationship between author, publisher and platform affects citation practices. Murray’s comparison of academic citations to hyperlinks makes an example like the canning blog so compelling as the mediated network can be followed, travelled, and interrogated. However, as a platform blogging remediates the relationship between author and publisher since authors also fulfill the roles of publishers. In the case of Food in Jars, McClellan determines the form, serialization and style of all content on her blog and negotiates her own relationship to advertising interests as well as produce content. This rearticulation allows the singular author full control over the citation networks published on her blog. It is this authorial-editorial control that sets the canning blog or lifestyle blog apart from publications such as the culinary section of other digital media.

Bibliography

Bensman, Joseph. “The Aesthetics and Politics of Footnoting.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 1.3 (1988): pp. 443-70.

Murray, Laura. “Plagiarism and Copyright Infringement: The Costs of confusion.” In Originality, Imitation, and Plagiarism, edited by Caroline Eisner & Martha Vicinus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. pp. 173-180.

Murray, Laura & Samuel Trosow. Canadian Copyright: A Citizen’s Guide. 2nd Rev. Edition. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013.

The post Other People’s Preserves: The Citation Economies of a Canning Blog appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Room of Our Own: Constructing and Curating the Open Access Archive for Transformative Works appeared first on &.

]]>In 2012, readers, media outlets, and literary critics were alarmed, appalled, and perhaps a little intrigued to find that E.L James’s erotic trilogy Fifty Shades of Grey had sold over 100 million copies worldwide and become a New York Times best-seller. Equally shocking to its mainstream audience was news of the novels’ scandalous origins: Fifty Shades of Grey began as fanfiction of Stephanie Meyer’s popular fantasy-romance YA series, Twilight (Bertrand). For their part, fanfiction authors had a different—albeit largely unified—response to the commercial success of Fifty Shades, which was to argue that the novels are neither radical nor well-written, and that an abundance of superior fan-generated erotica exists on the internet for free. Scores of articles like Aja Romano and Gavia Baker-Whitelaw’s “Where to Find the Good Fanfiction Porn” sprung up on blogs and digital news sources in an attempt to lead curious readers to popular repositories of high-quality fanfic. One such repository is Archive of Our Own (AO3), an open access database where users can read and post fanfiction. Unlike much academic research on the subject, this probe does not seek to answer whether fanfiction and other transformative works can or should be considered legal under the purview of fair dealing within copyright, but rather embraces the legal shades of grey that fanfiction inhabits in order to explore how repositories like AO3 provide a model for a productive, constructive open access archive.[1]

Fanfiction: What is it and where does it come from?

Fanfiction, often abbreviated as fanfic or fic, refers to narratives written by individual fans or fan communities based on the characters, settings, or plots of a canonical source text or transmedia franchise. Digital technologies scholar Bronwen Thomas posits that fanfiction “has long been the most popular way of concretizing and disseminating [fans’] passion for a particular fictional universe” (1). Far from simply rewriting the source text, authors of fanfic critique and transform of the canon, often by queering beloved characters or by giving voice to the women who are marginalized as little more than love interests in popular media.

The origins of fanfic as we understand it now can be traced back to the science fiction fanzines of the late 1960s (Tosenberger 186). Yet one can argue—and indeed many have—that fanfiction has existed as long as stories have been told, and that numerous foundational authors of the English literary canon, such as Milton and Shakespeare, were in effect authors of fanfiction themselves.

The advent of the Internet radically refigured the production and dissemination of fanfiction. In the 1980s, Usenet provided an early public platform permitting fans to connect and share their creative labour without the need for geographical proximity. The digitization of a formerly underground genre made it unprecedentedly accessible to anyone with an Internet connection, but this accessibility came at the cost of a reliable archive. Whereas printed zines had been physically circulated within small communities, posts on Usenet were often lost within days of creation until DejaNews provided the ability to access newsgroup content in 1995. While fanfiction expanded outward into the world, it also entered an age of ephemerality.

It was not until the introduction of the World Wide Web that fanfiction began to develop a system of digital archiving that lended works some measure of permanence. Single-fandom archives, hosted and managed by volunteers, collected, shared, and preserved stories as long as they remained online. Shannon Fay Johnson notes that the “more easily accessed and faster-paced virtual communities […] allowed for not only increased consumption, but also creation” (Johnson), and the downside to this wealth of creation was the organizational problem it posed for volunteer archivists. Fast forward to the late 1990s and early 2000s: the influx of creation produced a demand for massive multi-genre archives out of which were born, among others, FanFiction.net, the largest fanfiction repository in the world, and Archive of Our Own.

Building the Archive

Run by the non-profit Organization for Transformative Works, Archive of Our Own boasts more than 22,720 fandoms, 972, 600 users, and 2,549,000 works. Their goal, as listed in their mission statement, is to “maximize inclusiveness of content.” In order to do so, they grant open access to the works they host.

In “Open Access Overview,” Peter Subar quotes the PLoS definition of open access as “free availability and unrestricted use,” that is to say, content free of price and permission barriers. Both elements of open access are present in and the foundation upon which AO3 is built. Anyone with an Internet connection can read and leave kudos (similar to Facebook’s ‘like’) on stories in the archive. Although users do need an account to post, comment on, bookmark, and review fic, becoming a member is a free and non-discriminatory process. In terms of permission, guests and users alike are invited to download and save fanfics to their various devices as EPUB, MOBI, PDF, or HTML files, making them accessible both on- and offline. Moreover, fandom encourages authors and artists to excerpt each other’s work, translate it from one medium to another, or otherwise engage in reworkings of each other’s creations.

Screencap of the AO3 homepage.

In their FAQ, the OTW describes the ethos of AO3 as the following:

In the Archive of Our Own, we hope to create a multi-fandom archive with great features and fan-friendly policies, which is customizable and scalable, and will last for a very long time. We’d like to be fandom’s deposit library, a place where people can back up existing work or projects and have stable links, not the only place where anyone ever posts their work. It’s not either/or; it’s more/more!

Like open access journals, the OTW recognizes digital archives as a legitimate method of building a cultural history that is—if not accessible to all—at least accessible to most. Fans nevertheless have a right to be concerned by this intangible method of preservation. In 2002 and again in 2012, FanFiction.net’s owner, Xing Li, banned and remove all works rated NC-17 from the archive, effectively erasing them from fandom history if they had not been cross-posted elsewhere. The immaterial form of the open access archive is both its greatest asset and its greatest liability: the increased accessibility of fanworks only exists insofar as the archive remains free and online. While AO3’s blanket permission to download stories in various formats assuages some of the larger concerns about impermanence, it does not promise an eternal resting place for fanworks despite the creators’ hopes. Even if some works are preserved on hard drives and smartphones around the world, the comments, kudos, bookmarks, and links between fans and fandom would be erased from history.

In terms of accessibility, Archive of Our Own is attempting to move towards a model of universal access. Although most stories are in English, AO3 welcomes works in a variety of languages, and entire fan communities dedicate their time to translating and re-posting fanfics. Many fics are also transformed into podfic, the fan equivalent to the audiobook. Although only a fraction of the works on AO3 have been translated or recorded, the growing practice seeks to render fanfiction increasingly accessible to international fans, as well as to people for whom reading is not a viable mode of cultural consumption.

Framing Constructive Practice

As Peter Subar states of open access with respect to scholarly journals:

The purpose of the campaign for OA is the constructive one of providing OA to a larger and larger body of literature, not the destructive one of putting non‐OA journals or publishers out of business. […] Open‐access and toll‐access literature can coexist. We know that because they coexist now.

It is here that fanfiction’s legal ambiguity as derivative or transformative work comes into play. While an argument can be made that fanfiction is legally unpublishable because it borrows so much from source texts that are still in copyright, the case of Fifty Shades proves that fanfiction can be hugely profitable with the right modifications. Yet most fanfiction authors do not seek financial gain from their labour. When Peter Subar notes “the campaign for OA focuses on literature that authors give to the world without expectation of payment,” arguing that “they write for impact, not for money,” he could just as well be discussing fanfiction authors rather than academics.

Archive of Our Own therefore provides a clear example of the constructive nature of OA. Fanfiction and other derivative works do not replace or supplant commercial culture, nor do they attempt to. By its very nature, fanfiction requires original novels, films, television shows, and/or other cultural products to engage with. Rather than competing with publishers and producers, fanfiction operates in conversation with cultural objects in a way that is arguably comparable to academic scholarship. In order to enjoy a fic the way an author intended it to be enjoyed, the reader must have a measure of familiarity with the canonical work being addressed. Fanfiction ultimately demands the consumption of commercial culture, and its open access encourage synchronous creation and consumption.

The Gendered Archive

In The Future of Ideas, Lawrence Lessig notes that “[l]urking in the background of our collective thought is a hunch that free resources are somehow inferior” (27), and we see this rhetoric circulating in the discourse surrounding fanfiction. One aspect of fanfiction and fan communities that I have yet to explore in this probe is the question of gender. Unlike content found in open access academic journals, the content found on AO3 is largely generated, read, and validated by women and girls. It is therefore difficult to untangle whether fanfiction is disparaged because it is free, because it is not “original” work (is there even such a thing anymore?) or because of its demographics.

Furthermore, women have historically been the volunteer curators of fanworks. The open access archive therefore raises legitimate concerns about the long history of free labour undertaken by women—be it intellectual or affective. On the one hand, women and girls are building a shared community based on creative practice, and to lock such a community behind a paywall would be to silence those voices. On the other hand, if fanfiction acts as a promotional device directing consumers to a given franchise, open access archives to fanworks may be yet another instance of unpaid women’s work that goes unnoticed and undervalued while corporations and the (often male) guardians of the canon profit from free advertising. It might then be a productive enterprise to examine who benefits from the open access archive, and whether this kind of access ultimately devalues the artistic labour inherent in its creation.

[1] For a comprehensive insight into fanfiction’s fraught relationship with copyright law, see Kate Romanenkova’s article, “The Fandom Problem: A Precarious Intersection of Fanfiction and Copyright.” (Note that Romanenkova’s text engages with U.S. copyright.)

Works Cited

Archive of Our Own. Organization for Transformative Works. 15 Nov. 2009 (beta) archiveofourown.org/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2016.

Bertrand, Natasha. “‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ started out as ‘Twilight’ fan fiction before becoming an international phenomenon.” Business Insider, 17 Feb. 2015,www.businessinsider.com/fifty-shades-of-grey-started-out-as-twilight-fan-fiction-2015-2. Accessed 24 Sept. 2016.

Johnson, Shannon Fay. “Fan fiction metadata creation and utilization within fan fiction archives: Three primary models.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 17, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0578.

“Frequently Asked Questions.” Organization for Transformative Works. http://www.transformativeworks.org/faq/ Accessed 24 Sept. 2016.

Lessig, Lawrence. The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World. Random House, 2001.

Li, Xing. FanFiction.net. 15 October 1998, www.fanfiction.net. Accessed 23 Sept. 2016.

Romanenkova, Kate. “The Fandom Problem: A Precarious Intersection of Fanfiction and Copyright.” Intellectual Property Law Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 2, 20 May 2014, pp.183-312. Social Science Research Network, http://ssrn.com/abstract=2490788.

Romano, Aja and Gavia Baker-Whitelaw. “Where to find the good fanfiction porn.” The Daily Dot. 17 Aug. 2012, www.dailydot.com/parsec/where-to-find-good-fanfic-porn/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2016.

Suber, Peter. “Open Access Overview.” Earlham College. 21 June 2004, legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/overview.htm. Accessed 21 Sept. 2016.

Thomas, Bronwen. “What Is Fanfiction and Why Are People Saying Such Nice Things about It?” StoryWorlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-24. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/432689.

Tosenberger, Catherine. “Homosexuality at the Online Hogwarts: Harry Potter Slash Fanfiction.” Children’s Literature, vol. 36 no. 1, 2008, pp. 185-207. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/chl.0.0017.

The post A Room of Our Own: Constructing and Curating the Open Access Archive for Transformative Works appeared first on &.

]]>The post France’s ReLIRE Project: How to Reconcile Mass Digitization & the ‘Droit d’Auteur’ appeared first on &.

]]>In 2011, the ruling in a U.S. court case, Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust, set a precedent in copyright law by protecting the digital archives produced by libraries for preservation purposes under fair dealing. While the European Copyright Directive allows for the mass digitization of orphan works for non-commercial purposes, in Canadian copyright law the dissemination of such works is subject to the approval of royalties by the Canadian Copyright Board after a “reasonable” search for an unlocatable copyright holder. Commercial mass digitization projects, such as Google Books, have entered into agreements with both European and American publishing guilds. Between the library and the media company, a French digitization project for out-of-print books under copyright circumvents both fair dealing and publishing agreements in an approach that may resolve the question of how to balance “copy-right” with “democratic accessibility.”

In his seminal paper on the eighteenth-century book trade in France, “What is the History of Books?” (1990), Robert Darnton describes the life cycle of a book as a “communications circuit”: a stadial model that maps the material history of books from its author to its readers and emphasizes the actors involved in its production. Darnton’s model (and the dozens which followed) laid the ground work for the discipline of book history. While the discipline itself has recently come under fire by its own proponents for the way in which its emphasis on the material subject imagines a projected network of actors, this stadial model has influenced how we study the history of books.

Two decades of book history studies can be organized under a series of categories which correspond to the steps in Darnton’s communications circuit: studies of authorship; studies of publishing, its economy, and its materials; and studies of reading and readerships. Copyright, however, does not figure in this model. Or in that of Adams & Barker (1993), whose alternative but equally influential model for book production emphasizes the “whole socio-economic conjecture” — the intellectual, political, legal, and commercial influences on the book trade — over individual actors. Copyright is absent from these schemas due to the way in which it resists categorization. For those who have studied and written about copyright and the book trade, the political and economic pressures and legislative changes which structure copyright readily affect authors, publishers, booksellers, and readers. Copyright determines the price and availability of books, while it also creates a market for pirated and foreign reprints. Copyright both shapes a freely available public domain and protects a national literary canon.

If we were to place “copyright” or “the public domain” within Darnton’s communications circuit, it would belong along the dotted line that connects the “readers” of a book with its “author.” In this space of reception, the linear trajectory of a book’s transmission breaks down through the free circulation of books among readers and authors, who are also readers. More importantly, this model does not consider the temporal dimension of a book’s reception after publication. Without taking into account the longer history of books, book history studies are quick to disregard the titles and volumes which defy this model of transmission — the used books, rare books, and out-of-print books which have populated the shelves of second-hand and rare book sellers. Copies, reprints, and facsimiles have not been considered to the same extent as the publication of new titles. Even in large-scale studies of literary production, reprints of older titles are routinely removed from the lists generated by the British Library’s English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) or the American HathiTrust. Aside from a handful of studies concerned with mediation as opposed to the materiality of books — like Leah Price’s book, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain (2012), which discusses the libraries of middle- and working-class readers who purchase and acquire second-hand books — this segment of the cultural record has been relegated to antiquarians and the copyright library.

In many ways, the discourse used by the relationship between copyright legislation and the public domain resembles book history’s miasmic treatment of a book’s reception. In her article on the copyright and the public domain in Canada, Carys Craig describes the relationship between the two institutions as dynamic rather than complementary and intrinsically related to creative uses. For Craig and other legal scholars, the link between copyright and cultural production remains elusive:

“The copyright system should be regarded as one element of a larger cultural and social policy aimed at encouraging the process of cultural exchange that new technologies facilitate. The economic and other incentives that copyright offers to creators of original expression are meant to encourage a participatory and interactive society, and to further the social goods that flow through public dialogue. [. . .] The public domain that is irreducibly central to the copyright system (Drassinower 2008: 202) protects the cultural space in which this happens.” (78)

In this context, copyright and fair dealing are both driven by a user-based economy in which access to materials both under copyright and in the public domain becomes an important issue. In their user’s guide to Canadian copyright legislation, Laura Murray and Samuel Trosow discuss the question of access in relation to the current copyright regime through alternative funding models. How can works be made available “without undue constraints to those members of the public who want to engage with it” (233) while also respecting the labor and rights of owners? Answering this question has become an imperative for any copyright economy in the wake of digitization and the possibilities it offers for the dissemination of rare and restricted materials to a larger audience. Fair dealing, Open Access, and Creative Commons licences are only preliminary answers to this question: they offer only a limited solution for unlocatable copyright holders.

Article 5(2)(c) of the European Copyright Directive provides an exception to copyright infringement for non-commercial archives and libraries, educational institutions, or museums, however this exemption is limited to specific acts of reproduction and only applies to orphan works, not out-of-print works (Borghi & Karapapa 12, 88). While orphan works are works for which the rights holders are unlocatable, due to lacking information, out-of-print works are published works that are no longer commercially unavailable. Out-of-print works are often still protected by copyright as rights holders or publishers have withdrawn these books from circulation for commercial or authorial reasons (cf. the French “moral right of withdrawal”). To compensate for the corpus of works that are no longer available either commercially or through fair dealing, France passed an act (loi n˚2012-287) which modifies copyright law to incorporate a mechanism regulating the use of unavailable works through mandatory collective management. The regulation of twentieth-century out-of-print works under copyright relies on two main elements: the Registre des Livres Indisponibles en Réédition Éléctronique (ReLIRE; Register of Unavailable Books for Electronic Republication) and a collective management organization (the Sofia). For the purposes of this discussion, I am most concerned with ReLIRE.

The register itself serves to inform authors, editors, and rights holders that their works may enter collective management. Through this mechanism they may see their works republished and made available without undue financial burden on the rights holders themselves. Since 2013, each year on March 21, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF, France’s copyright library) publishes a register of 60,000 commercially unavailable twentieth-century books under copyright to enter collective management for electronic republication. The list is available online and authors, copyright-holders, and editors that hold copyright have six months to opt-out of the list. After September 21, the works on the list enter collective management by the Sofia and editors that hold copyright in print are offered a 10-year exclusive right to distribute the work electronically if they reply within two months. After this delay, editors that hold copyright but are unable to prove their claim, original editors that fail to respond to the initial inquiry, or editors that never held copyright originally may hold a 5-year non-exclusive right to distribute the work electronically. In all cases, editors are required to publish a digital edition of the work within three years. Authors may petition to have their works removed from the list at any time under France’s “moral right of withdrawal.” Editors who petition to have works removed from the list (whether before or after the September deadline) are then legally obliged to publish the work within two years. Once the digital edition has been republished, it is made available to readers through the publishers’ digital library and Gallica, the BnF’s digital library.

To understand how ReLIRE operates unlike fair dealing under Canadian copyright or the European directive on orphan works, two aspects of French copyright legislation should be considered:

- The loi n˚2012-268 which created ReLIRE relies on a blanket authorization to reproduce out-of-print works under copyright which places the burden of proof on copyright holders. However, authors, right holders, and editors who make themselves known receive remuneration from the Sofia on behalf of the publishers of the new electronic editions.

- “Le droit de prêt,” or the right to borrow, which describes the remuneration paid by libraries and other educational institutions when copyrighted material is borrowed by or distributed to patrons.