The post A day in the life of my dream job: Colonial Williamsburg historic trades – The Margaret Hunter Shop, Milliners and Mantuamakers appeared first on &.

]]>- Can you describe your working space. Be as detailed as you like.

2. What are the practices of your daily life?

- We are open to the public between 9am-5pm 7 days a week, with Fri/Sat being only the 3 milliners/mantua-makers and Sun/Mon the tailors’ days. We show up before 9 am, some of us arrived dressed in our 18th century clothing, while others come in modern wear and change at the shop. We write up an interpretive schedule for the day based off of who is working that day, what meetings are occurring, etc. We keep the schedule as even and balanced as possible. With the interpretive schedule set, we are able to configure the rest of our day around our speaking time. Usually we have sewing projects that are demanding our attention, but we are still a modern museum with modern day responsibilities, so there are always emails to write and meetings to schedule. We also fit in our research when we can amongst our other responsibilities and lunch too. Usually we head home between 5 and 5:30 every night.

- What do you ‘do’?

We are a par to the Department of Historic Trades and Skills at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Our responsibility is to research, rediscover, practice, preserve, and educated the public on our respective trades. All but one of the shops in the department have an apprenticeship program where we have created an educational based employment opportunity where after a series of projects and research, the apprentices are able to graduate to journey(wo)men. Apprenticeships usually last between 4-7 years, and you are encouraged to stay on as a journey(wo)man after completing your apprenticeship.

I currently am about half way through my apprenticeship, which specifically means I have completed the millinery portion of my and am into mantua-making (dressmaking). My sewing projects revolve around my apprenticeship demands and the demands of the various projects and programs that the shop is involved in. Researching my trade and the objects of my trade is done through almost exclusively primary documentation, ranging from newspapers, magazines, books, original images, and garments. Occasionally, we will reference a Janet Arnold or Norah Waugh book to see how they have patterned original garments or skim their primary research that they’ve published in their secondary source. We practice what many call “Reverse Archeology” or “Experimental Archeology” where the practice of making an object is the point of the study. We recreate items to better understand what they are, why they existed, who used them, and how they were made. Sometimes this means that we are producing some unusual pieces that spark a lot of questions, but the experimentation is what makes our shop so great and helps us understand the past in a much more comprehensive way. We are not here to make reproductions; we are here to understand two 18th century trades that were extraordinarily popular as they were diverse.

Though our museum focuses on telling the story of Williamsburg, Virginia through the American Revolution, the trades department is a bit different. Our shop, in particular ranges in projects from the early 18th century through the 1840s, but we do try and keep the 19th century sewing above stairs and out of the public eye if we can help it, and it doesn’t happen very often. We interpret western fashion from roughly 1774 – 1782 in the shop, and the pieces on display all help tell that story. The clothing we make is not limited to Virginian dress either, as with the lack of primary resources that highlight Virginian women’s dress, we wouldn’t have that much to make. So we have a broader reach in our production, looking at clothing in the USA, England, France, and I’ve even taken a study trip to Sweden. The variety of skills and techniques that we’ve seen from Western Women’s clothing in the 18th century has raised a lot of questions for us, and by reaching out beyond our borders we are hoping to find the answers to better understand the women who practiced our trade, what they did the same and what they did differently.

- What is the knowledge produced?

To continue what I stated above, our goal is to better understand the trades of 18th century millinery and mantua-making, and through the study of these trades gain a grounded and well-rounded understanding of 18th century society and culture as a whole. From a practical perspective, we also figure out how to make the variety of objects that were worn by our ancestors to such a degree that we are able to educate the public through our interpretation and hands-on workshops.

De-bunking mythology is another goal of our shop. My personal research has been focused in 18th century hairdressing and hair care, and a lot of mythology around hair hygiene I’ve been able to debunk through the careful study of primary documentation and experimental archeology. For example, the pomades and powders that were used in hair dressing did not ‘stink’ of bacon or mutton, but instead were cleaned of all animal scent and then heavily scented with essences and essential oils which results in clean smelling and fragrant hair.

- How does it take shape in material form?

It takes shape by the objects we make and the clothing we wear. All the objects that are displayed in our shop (that are textile/fashion related) we have made, by hand, in the same manner and techniques that were done in the period. We make the clothing we wear in the shop, and we are able to help others create their own 18th century clothing through hands-on workshops where we teach the skills and techniques of the milliner and mantua-maker.

- Are there problems with your space?

Probably only that which can be expected; it’s too small at times for all of us, the public, and all of our things. With that being said though, there is nothing better than sitting at that work board on a brisk cold sunny morning with a warm cup of coffee looking out onto Duke of Gloucester St.

- How does this affect your work/knowledge production?

It’s the struggle of the trades person, regardless, I believe, of what shop you are in. Customer service comes first, and if that means putting down our project to answer a question, regardless of that project’s deadline, that is what you do as a Colonial Williamsburg interpreter. 18th century milliners and mantua-makers could, and did, work in more private and quiet settings. So their productivity was no doubt larger than ours, but it’s just how the job is. Another issue is the ability to research as a result of staffing shortages or project demands. There is a lot of juggling that comes with this job, and one of the biggest challenges for a new apprentice to face is figuring out how to handle all the different demands and responsibilities of working in a trade shop. Though, I have to say, I am never, ever, bored.

- What lead you to do the work you do?

All of us who work in this shop will answer this question differently, but I am only going to speak in regards to myself in this case, so please keep that in mind when reading this. I qualify myself as a Dress Historian who makes the clothing she studies. I’m not a re-enactor nor am I a costumer. As an undergraduate studying Art History, History, and Theatre, I was and always had been very interested in historic clothing and fashion. Between my junior and senior years of undergrad I spent a summer working in the Margaret Hunter Millinery shop 4 days a week and 1 day a week with Linda Baumgarten the Head Curator of Dress and Textiles at Colonial Williamsburg. The hands-on and sort of trifecta approach (studying, making, wearing) to studying 18th century dress in the millinery shop had a very strong draw for me as an academic. The practice of being able to make and wear the clothing I study has given me a deeply intimate knowledge of the clothing and a better understanding of the culture and its people. Working for Colonial Williamsburg, in my opinion, is the best place to study 18th century women’s dress in the way I wanted to study it.

The post A day in the life of my dream job: Colonial Williamsburg historic trades – The Margaret Hunter Shop, Milliners and Mantuamakers appeared first on &.

]]>The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>By Sabah Haider

In this interview for the graduate seminar HUMA 888: Mess and Method [Fall 2015, “What is a Media Lab?” edition], Sabah Haider, PhD Student at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University interviews Dr. Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV and Associate Professor, History and Sociology and Anthropology (joint-appointment), and Canada Research Chair in Post-Conflict Memory and Ethnography & Museology, at Concordia University. In this interview, Haider seeks to gain insight from Lehrer on how interdisciplinary research engages with technology and the fast evolving Digital Humanities.

EL: First of all, I should begin by saying that CEREV is in the process of separating itself from our lab space, which itself is being renamed the Centre for Curating and Public Scholarship. I didn’t want my own preoccupations with difficult, contested histories and cultural issues to dominate a lab space that could be accessible to many more users who share my concerns with using exhibition or curatorial work as a form of public scholarship. So in the future CEREV will be one of a number of units and groups of people using the CCPS lab platform. It was also a question of stability. There is no lab work without lab funding supporting lab staff, and the model we had was too narrow to be financially sustainable.

SH: The Centre for Ethnographic Research and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Violence (CEREV) is a media lab that fosters the intersection of many disciplines/disciplinary approaches to produce broader understandings and to challenge existing understandings around ideas of the exhibition of trauma and violence. On the CEREV it states the centre was established “to create a community of researchers and curators and produce new knowledge around issues of culture and identity in the aftermath of violence.” In relation to the practical side of this — how can you describe or explain how knowledge is produced at CEREV?

EL: Different kinds of knowledge are produced at different nodes in the network of sites and people that make up CEREV. We have an incubator room with computers, and more importantly a round table, where postdocs and students (and sometimes me) meet and talk; we have our exhibition lab, where curatorial experiments and public presentations take place; periodically we have large-scale public exhibitions at various local or international sites; we meet in homes or cafes or my office for more casual mentoring chats; and then we have our website and Facebook page. These are all parts of “the lab,” and the spatial aspect is centrally important to what kind of knowledge is produced, and who participates in its production. I would say that knowledge is produced individually in reading, looking, and thinking; it is produced socially in interdisciplinary, multi-level, and inter-subjective dialogue, negotiation, constructive mutual challenging (sometimes uncomfortable), and in shared experience among differently positioned people; it is produced in a process of making, building, and experimenting with various media; and (for those who only come into contact with things we produce) I hope knowledge is produced in inspiration and the generation of new ways of thinking and seeing. For me the key to “lab-ness” is the special process of collaborative creation – we all help each other to think through and envision a product even if it ultimately is put out into the world under a sole author. I’ve always liked (and used) Gina Hiatt’s manifesto, “We Need Humanities Labs.”[1]

SH: How does CEREV engage with digital technologies to stimulate this? Since the lab’s creation in 2010, has there been an increasing interest in also exploring relevant digital forms and practices, in parallel with the growth or expansion of the digital humanities (DH), particularly as the DH has spawned a seemingly infinite number of digital tools that facilitate new types of exploration?

EL: Playing with new technologies can generate ideas, and that’s why we have our indispensible Director of Technology, Lex Milton, who crucially has a background in educational technologies. He’s an excellent muse, who can listen to logo-centric humanities scholars and help them think about how they might expand and “curate” their projects in productive ways by imagining what technology can do. But I’m not so compelled by projects that use technology as a starting point – or perhaps I mean humanists are not best-positioned to start from everything that “can be done” and then try to figure out how to use XYZ bells and whistles in their own work. Rather I think we do best when we have a particular problem we want to solve – like getting multiple voices or perspectives visible/audible around an object, or getting people who are far away from each other into dialogue, or creating options for accessing and exploring massive archives of information in a single space, or moving people emotionally – and then thinking about what might help us do that. This is when dialogues between humanists (or social scientists) and people with technical and creative skills are most productive. We dream aloud, we share our challenges, and they suggest possible solutions using the technologies that exist. And we humanists push the tech people by asking them “do you think you could make it do XYZ?” It’s a really exciting dialogue, and the final products are always something neither party could have envisioned on their own. We stretch each other.

SH: What are some of the emergent media forms that the lab has incorporated/is incorporating? How can you describe the materiality of the CEREV space? (i.e. mobile, virtual, etc.) What kinds of material forms (i.e. forms of output) does the knowledge produced at CEREV take? What types of ethnographic experimentation has/does CEREV facilitated/facilitate?

EL: I alluded to the various materialities linked to the CEREV lab above. We do have a couple of dedicated physical spaces, and the exhibition lab in particular has a lot of technical tools – projectors, mobile screens (some of them touchscreens), iPads, surround sound capability, etc. – as well as analog ones like pedestals and screens and curtains. And then lots of recording equipment for still image, video, and sound. We facilitate whatever kinds of technology-enhanced fieldwork people want to do, which includes documentation as well as bringing various pre-produced media to field sites, or to co-produce media with various research interlocutors. The forms of output range from ideas to lectures, blog posts, scholarly publications, videos, and exhibitions.

SH: Most of the work of CEREV affiliates appears focused on themes of meaning, affiliation, curation and exhibition. Trauma and suffering, as you have identified, encompasses victims, perpetrators and bystanders or observers. Has/does research at CEREV explored/explore all three of these perspectives/positions — or relationships between them?

EL: I would say yes, we’ve created work looking at these positions and their interrelations. PhD student Florencia Marchetti has been creating field-research-based videos made at a site of a former detention and torture centre in Argentina, which she then uses to seed discussions among the people who today live nearby – some of them were bystanders at the time the centre was operational and they are bystanders to memory today. Students re-curated the video testimony of a Montreal Holocaust survivor to explore victim narratives and their forms and uses. And my own work has dealt with how to raise difficult questions that implicate audiences in their own collective “perpetrator-hood” regarding historical violence and its contemporary legacies or ongoing prejudices. These are just a few projects but they cover all the positions you mention.

SH: What does it mean to have this kind of space as an interdisciplinary scholar — a ethnographer/historian/anthropologist?

EL: It’s mostly challenging. It makes one realize how comfortable text is – both in terms of the limitations of creating it and its relatively limited reception. When you have to deal with capturing and transmitting so many more dimensions of experience, and when such a large public audience can respond (and challenge) what you create, one is confronted with the limitations of one’s own view.

SH: Has anyone outside of your research community (i.e. from the wider “at large” community taken interest in your space, and if so why and how?

EL: Yes, people from various communities, like the Black community in Little Burgundy, or members of the Armenian, Palestinian, and Jewish communities, as well as AIDS activists are just some of the groups that have seen in the lab a space to gather to create and debate representations of history and culture relevant to their own groups. You can read a bit more about the projects we’ve done in the lab, and my own trajectory, at: http://cerev.cohds.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Abell-interview-with-EL.pdf

// END

[1] Hiatt, Gina, “We Need Humanities Labs”, Site URL: <https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2005/10/26/we-need-humanities-labs>

FOR A FULL PDF OF THE INTERVIEW CLICK BELOW

HUMA 888 Interview_CEREV_Erica Lehrer_by Sabah Haider

The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>The post “What do you mean that noticing one thing can make the other things disappear?”: On Affective, Unpaid, and Invisible Labour appeared first on &.

]]>The Numbers

In 2011, the American organisation VIDA (Women in Literary Arts) began publishing a yearly review of major literary publications that tallied the gender ratio of writers, reviewers, reviews, and pieces published. In 2012, the Canadian non-profit organisation CWILA (Canadian Women in the Literary Arts) followed suit with their tally of gender inequity in the Canadian literary publishing industry. Both organisations have continued to release their annual counts, and have begun to develop more nuanced methodologies to account for more than just female/male gender identification, such as VIDA’s 2014 Women of Color VIDA Count.

CWILA has also been working to account for the voices of writers outside of the male/female binary, as well as to develop an ethical and productive methodology of accounting for other representational inequities, such as diversity in racial and sexual identities. Unsurprisingly, the data found by both organisations has invariably skewed towards a large portion of the work—reviews, reviewers, texts, editors–being done by white men. While the overall numbers have been gradually improving since the initial imitative (no doubt partially in response to the increased pressure and attention the counts have received) a persistent trend is that male reviewers are primarily reviewing work by other males. This speaks not only to a literary publishing culture that values the critical and curatorial voices of men, but also to one that sees the work of men as inherently worth more in the circulation of public intellectual and cultural discourse. CWILA Chair Erin Wunker coined the term “The CWILA Effect” in 2014, to address the organisation’s conclusion that, while the numbers may be gradually approaching gender parity, underlying systematic and structural inequity remain. In the editorial preface to the annual release of data from 2014, Wunker also notes that the majority of the work of counting and disseminating the numbers is unpaid labour done by women.

Who’s counting?

As is often the case when discussing systematic inequality or marginalisation, the statistical data is only one twig in a deeply rooted exclusion. In other words—there’s a lot more going on than what can be accounted for in a pie graph. We can read the quantitative inequality documented by CWILA and VIDA in conjunction with Debbie Chachra’s critical inquiry into the gendered implications of the language and terminology circulating around “maker culture.” As Chachra notes in her 2015 article “Why I am not a Maker” for The Atlantic, contemporary maker culture values material production, as well as the image of a solitary Maker, above the less tangible or visible work that supports making. Chachra also notes that other kinds of making happen outside of the academy, the workplace, and traditional or documentable spheres of labour.

I am not a maker. In a framing and value system is about creating artifacts, specifically ones you can sell, I am a less valuable human. As an educator, the work I do is superficially the same, year on year. That’s because all of the actual change, the actual effects, are at the interface between me as an educator, my students, and the learning experiences I design for them. (Chachra)

What about work that is not seen an innovative or revolutionary, but rather as quotidian, expected, permanent, and uninteresting? Chachra notes that the kind of labour seen as static or fixed—education, caretaking, mentorship, repair, analysis—is actually more dynamic and vital than it may seem. The kind of work that takes place in the classroom or office, in the home, or in less tangible locations often has no physical product to present. Chachra addresses how this kind of work goes unnoticed and undervalued, especially in an increasingly capital-driven and corporate university culture. The labour of care, minding, and other kinds of emotional or affective labour is disproportionately performed by women. As Chachra notes, there is invisible structural support behind most of the products or labour that are celebrated as the ideal kind of making: “Walk through a museum. Look around a city. Almost all the artifacts that we value as a society were made by or at the order of men. But behind every one is an invisible infrastructure of labor—primarily caregiving, in its various aspects—that is mostly performed by women” (Chachra). There is no system of circulation, reward, or capital for these kinds of making—or at least no unified or highly visible one similar to the way science, tech, and arts making culture circulate the products of labour. As we saw in the Star reading on Infrastructure—the kind of work that makes an infrastructure of support is often invisible until broken. But what if this kind of labour is pointed out, or stopped altogether, before it is broken? How do women, and other performers of this kind of undocumented and uncompensated labour, find a language or methodology to pre-emptively discuss the issues involved?

Whose work?

In her 2015 collection of prose-poems, Garments Against Women, Anne Boyer considers the material and affective labour performed by women. Half memoir and half meditation on contemporary modes of “making,” Boyer considers how much of the labour necessary to quotidian existence—the work of care—is disproportionately performed by women, and goes largely uncompensated.

I will soon write a long, sad book called A Woman Shopping. It will be a book about what we are required to do and also a book about what we are hated for doing. It will be a book about envy and a book about barely visible things. This book would be a book also about the history of literature and literature’s uses against women, also against literature and for it, also against shopping and for it. (Boyer 47)

Boyer’s poems, as well as her other critical work, explore the material and affective labour that women perform when they either support or create work of their own (often, both!), as well as the costs of this work. As she states in an interview with Amy King at The Poetry Foundation, “literature is against us.” Throughout the collection, Boyer ties issues of gendered labour and work into modes of creation and artistic work by women. Drawing on the colonial history of canonical literature, Boyer argues that the ways in which literary production, education, and other large-scale forms of artistic production are constructed in ways that value a certain kind of Maker and a certain kind of product:

but by “us” I actually mean a lot of people: against all but the wealthiest women and girls, all but the wealthiest queer people, against the poor, against the people who have to sell the hours of their lives to survive, against the ugly or infirm, against the colonized and the enslaved, against mothers and other people who do unpaid reproductive labor, against almost everyone who isn’t white—everyone who has been taken from, everyone who makes and maintains the world that the few then claim it is their right to own. (Boyer)

As Boyer’s work demonstrates, the scope of inequality and exclusion in literary history and contemporary circulation is large, messy, and difficult to organise in data sets. How do we account for the variety of ways in which We and Us are excluded from the academy, publication culture, and a myriad of other corporate and canonical hierarchies?

While work like CWILA’s and VIDA’s continue to make invaluable interventions into inequity in literary culture, there is always the question: well, what next?

so….What next?

How do we take account of work and labour— and the inequities in that labour—that are less easily quantified or counted? What spaces and system do we create, or have to create, in order to bring these issues into public discourse? One possibility is to open up safe and productive spaces (digital or physical) for feminist discourse. Both CWILA and VIDA have begun other initiatives since beginning their data work, such as a paid critic-in-residence program, as well as regularly featuring interviews with women working in Canadian and American literature, among other initiatives. Another possibility that Chachra raises is to reject language that privileges a certain kind of discourse around productive labour.

I understand this response, but I’m not going to ask people—including myself—to deform what they do so they can call themselves a “maker.” Instead, I call bullshit on the stigma and the culture and values behind it that rewards making above everything else. (Chachra)

Chachra’s call is to not reframe how her work—and the work of her colleagues—is seen and read publically, but rather to shift the focus altogether, and to consider the value of affective work. Boyer notes that the work that is performed (in her case, the work performed by a single mother stricken with chronic illness and cancer) is just as noteworthy as what is not performed because of these implicit structures of gendered labour.

There are years, days, hours, minutes, weeks, moments, and other measures of time spent in the production of “not writing.” Not writing is working, and when not working at paid work working at unpaid work like caring for others, and when not at unpaid work like caring, caring also for a human body, and when not caring for a human body many hours, weeks, years, and other measures of time spent caring for the mind in a way like reading or learning and when not reading and learning also making things (like garments, food, plants, artworks, decorative items) and when not reading and learning and working and making and caring and worrying also politics, and when not politics also the kind of medication which is consumption, of sex mostly or drunkenness, cigarettes, drugs, passionate love affairs, cultural products, the internet also, then time spent staring into space that is not a screen, also all the time spent driving, particularly here where it is very long to get anywhere, and then to work and back, to take her to school and back, too. (Boyer 44)

Boyer’s work in Garments Against Women provides one alternative mode of quantifying affective labour and documenting the experiences of those who perform it. Her collection traces her affective labour of caring for herself, her daughter, and others, and also the material labour of work such as garment-making, writing, shopping, cooking, and caring for one’s appearance. She states “[t]here is no superiority in making things or in re-making things. It’s like everything else[…],” suggesting that no single act of labour that she can perform (or can’t perform) is innately more valuable than another (Boyer 20). The intersections of the various kinds of labours are also considered. Through this tangle of information and memories emerges a detailed account of what it means to try and write from a place of precarious employment. Could Boyer’s account be used in public, academic, and personal discussions around the kinds of labour women perform, especially when they are also artists, writers, and public voices? I’d say yes, but others may say –what could be less objective, quantifiable, or analytic than poetry?

Can you count feelings?

As a member of the precariat, Boyer recognises that certain critical experiences are poorly translated into the accepted or valued modes of knowledge dissemination. In many ways, her collection offers a radical alternative to the documentation, curation , and framing of women’s work. In the opening poem “Innocent Question,” Boyer asks how we quantify what does not fit into formulaic modes—

Some of us write because there are problems to be solved. Sometimes there are specific, smaller problems. A friend who has a job as a telephone transcriptionist for people who can’t hear has had to face the problem of what to do when one party he is transcribing has sobbed.

(He puts the sobs in parentheses.)

This is the problem of what-to-do-with-the-information-that-is-feeling. (Boyer 3)

So…is poetry the (a) solution? Can it be the radical alternative for opening up discussions about issues such as contract-academia, the value of affective labour, and how to talk about women’s work? Boyer states that poetry is a vital methodology for addressing these issues, but that it also has limitations in what kinds of privilege allow it to be produced and circulated.

Then there’s not much time left for anything other than whatever we have to do to take care of ourselves so that we can sell more hours of our lives. Reading—even literacy—can always be, and for some kinds of people always has been, a minor rebellion, but it’s probably never a full scale revolt. There’s a genius in bodies, too, in hands, in seeing and hearing, in feeling, in arrangement, in taking care, in imagining, in saying words aloud. But the world as it is makes reading particularly hard, like we should read just enough to get some bad ideas but never enough to finally get to the helpful ones. (Boyer)

As with all public and published forms of expression, poetry and literature has its own set of privileges and limited access. So is it the answer to including the personal, subjective, and affective in scholarly and formal discussions of labour? Combined with work such as CWILA’s and VIDA’s, my inclination is to say yes. One such example of a creative and critical space is the blog Hook & Eye: Fast Feminism, Slow Academe, which features posts by a cohort of women working in (or alongside) Canadian academia. The posts, while written by experts in the field of critical writing, are unique in that they work to address the subjective, affective, and personal issues and experiences that are difficult to talk about in quantifiable terms. The blog acts as a safe space to talk about what it means to do feminist work and still end up with a paycheque. Some issues addressed in the past handful of months include 1) how to prep grad students for the reality of the job market, 2) how to structure and regulate over-booked office hours, 3) how to effectively make mid-week conference trips, 4) how to include vital information on anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-sexist work in undergraduate classes outside of the official and approved syllabus, and 5) how to navigate job precarity, and whether or not to discuss it publically. These topics all speak to the kind of unpaid labour that is specifically performed by contract-academics, though they also speak to a more universal issue faced in women’s work: how to evoke the personal, political, and poetic in structures of knowledge production that work to exclude those means of expression. Like CWILA, VIDA, and Boyer’s writing, Hook & Eye performs the kind of women’s work that is unpaid and often unacknowledged, but critical.

In my last probe I wondered about how we frame the voices of young women, such as poet Trisha Low. An assumption about these voices is often that the critical work is overshadowed by the emotional, or undervalued by the excess of emotion.

When discussing issues of labour, of women’s work—whether academic, domestic, critical, affective, or otherwise—do we need to use the quantitative methods of critical subjectivity, or should we be moving into a new form of knowledge dissemination that can account for this work? What kind of Media Lab, or any kind of center, could be successful at circulating this knowledge? My guess would be that it will not be centralised, but spread wherever the work and the discussions becomes possible: in poetry, in self-published blogs, in underfunded magazines such as GUTS: Canadian Feminist Magazine, or in the conversations that women have that are undocumented. As Boyer asks, what do we do with the information that is feeling? How do we move these vital thoughts and experiences into the structures that in many ways perpetuate the issues to begin with? Or do we look towards new spaces, new terms, new framing of the work done by women?

That we are alienated, that we are unsure, that our next month is so regularly worse than our this one, are things common to many of us, are these hard and ordinary things of life as it is now which an algorithmic display of affect can’t soften. The feeds could weep all day long, and it wouldn’t mean they won’t also be crying harder tomorrow. So what are we supposed to do? (Boyer)

WORKS CITED & CONSULTED

Boyer, Anne. Garments against Women. Boise, Idaho: Ahsahta, 2015. Print.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27.4 (2011): 252-60. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

The post “What do you mean that noticing one thing can make the other things disappear?”: On Affective, Unpaid, and Invisible Labour appeared first on &.

]]>The post Weaving as Cultural Practice: What time of the year is it? appeared first on &.

]]>The selfie of my loom

My loom is like a housewife’s ill-used treadmill. It sits behind me in my office/studio beckoning me to ‘work’, to weave something, anything! Instead, at this point in my life I really need to read stuff, write things. My work table doesn’t hold fabric, waiting to be made into a suit. No. It holds collated readings for the grant proposal. Readings for probes. More readings for the paper I must write for the end of the term. The things is though, I’d rather do anything but write. And so, like a good academic, I have perfected the act of procrastination. Oh the ways that I can procrastinate, even though I know that if I would just sit here and write, there would be time left in the day to create. By the way, this is my loom’s first ever ‘selfie’, and the second ever ‘selfie’ of myself. I’m not usually one for modern technology.

For this probe, I am going to talk about weaving. This had been my plan since first reading the abstracts for the readings for this week. I weave to develop a better understanding of how people in the 18thC lived. I weave to firmly grasp how expensive clothing is, so different from what we see today. Yesterday I went out and spent 200$ and bought two pair of jeans, four T-shirts and four packages of underwear. Two Hundred dollars; that was all it cost for all those clothes. That is not the real and true cost of those items of clothing. In fact, if we were to harvest the fibres, process them, spin them, weave or knit the cloth, then make the garments, we would have a better understanding of the true cost of the clothes that we wear. And we would be outraged. But, back to weaving.

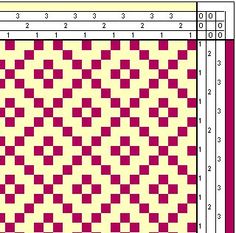

This is a weaving pattern. The main body of the pattern gives you a diagram of how the weave structure will look as you are weaving. The pattern in the cloth. There are many different varieties of weave structures that will give you different patterns in the cloth, and are used for different reasons. The jeans we wear are a twill weave. Twill stretches a bit and so makes our jeans more comfortable to wear, even if they don’t also have a stretchable fibre in them. Dish cloths tend to be woven in a variation of the twill that produces a waffle-like effect in the cloth. This allows for better containment of soap, and more scrubability. Dress shirts are woven with a plain weave structure. This makes ironing them easier and allows for a crisper finish.

The top bar of the pattern tells you how to thread the loom to achieve the pattern. The top right hand corner tells you how to tie-up the foot pedals to the loom. The bar that runs down the right hand side of the pattern tells you how to weave, giving you which pedals to press down with each step. This text allows weavers of many generations to understand and recreate cloth that may have been first woven hundreds of years ago. The structure of a weaving pattern has not changed in a very long time.

My loom is called a ‘colonial box loom’. It is a modern loom based on the style of looms that would have been created and used in the 18th century. My loom came to me in a very interesting way. This may seem like a bit of a side-bar, but is relevant to the story. Two years ago, I was able to spend a summer with the Nova Scotia Centre for Craft and Design. During that summer residency, I had full access to their weaving studio. My project was to recreate linen textiles from the 18th century. I had never woven with linen before, and there were some things I wanted to create for our re-enacting kit. Among these projects were dish cloths and towels, chair strapping, a tablecloth, and a length of shirt cloth. The shirt cloth was to be the major project, with the others being made up as time allowed. The shirt cloth yardage was supposed to be about 15 metres long, enough for several shirts and some aprons. Each of these textiles were based on historical weave patterns from a book written in the late 18th century, and the check pattern for the shirt cloth was based on a sample in the MET museum in Boston.

I began on July 1st. It took a week to wind off the threads for the warp of the shirt. The warp threads run the length of the cloth, and are what is threaded through the loom. As a weaver winds the warp threads on the warping mill, he/she counts off the pattern of the weave structure. I had to first determine how wide I wanted the cloth to be, and then how many threads I wanted to use, and in what order, colour-wise. This idea was then counted off while I wound the warp so that I would have a consistent pattern across the cloth, and would have enough threads to make the desired width.

This shirt warp took over a month to actually wind on to the back beam of the loom, ready to weave. The warp was wide, 30 inches. Normally it takes two of us to get a warp on to the loom so that I can thread it. This warp took three of us. I had to wait for pairs of friends to be willing and able to come into the studio with me. (In the meantime, I continued on with some of the other projects that I had on the go.) Also, the linen was very hairy thread, and liked to catch itself on the other threads, making large snarls. To ‘condition’ the threads to ease in this problem, I starched the threads once I took them off the warping mill. I then continuously sprayed the threads with even more starch as we wound the warp on the loom. Little did I know that the threads drying out would be a major issue (problem #1), and that my starching may have caused yet another issue (problem #2).

We finally got the warp on the loom and I began to thread. This took me two solid days of work. The warp was 30 inches wide and there were roughly 20 threads per inch. Roughly 600 threads to thread into the heddle eyes. And then threading 600 threads through the reeds. I really do enjoy this part of the weaving process. I put a Latin mass on my iPod and completely get into the zone of hanging in my loom, threading things. I really do hang inside the loom. The front bar comes off, and I get a chair inside as closely as I can to the heddles, and then I hang my arms over the beater bar and thread. It is tiring though, and hard on the body.

When I finally got everything ready to go, I decided to start fresh the next morning.

I usually start working very early in the morning, even when working in a studio outside my home. During this residency, I would start about 7am. The centre itself would open about 830am, with the public starting to come in to visit about 9am.

And so I go into the studio, get settled in for the day, sit down and begin to weave. I start with a really heavy thread. This is done to check the tension, and also to allow for a nice strong start to the weave. I may have thrown about five weft threads when I noticed that my tension was getting worse, not better. In fact, it was reaching catastrophic failure. WTH? I got up and then I noticed the back of the loom, where 15 metres of threads were at one time all nicely wound on the back beam. The threads that had been so lovely the night before had become a snarled mess. They slid off the sides of the coil of threads (problem #3), and were just a mess of thread on the back of the loom.

And here is where I was really glad that I was alone in the studio. The air turned blue as I cursed that warp in three languages and threw an epic temper tantrum. EPIC, I tell you, with tears and everything. I was still having a good cry, pulling the warp back off the back of the loom when a tourist walked in and said hello. He took one look at me and understood what was going on. He told me that his wife was a weaver, and that when she had this happen to her, he would disappear off to the pub until she called and told him it was safe for him to return. My first angel walked into my residency. This lady told me what was happening, told me it could be fixed, and then spent a good amount of time with me helping to get the warp off the loom without me cutting it to shreds. She told me how to fix problem #3. That weekend, my husband Pierre, friend Garth, and I got the warp back on the loom. I could finally weave.

This was the first of August. I had a little over a month left to go on my residency and far too much to accomplish. I set to weaving. This shirt warp proved to be difficult the entire time. I had to continually starch the warp as I wove. I got into a routine of spraying the warp with starch, while I waited for it to dry just enough, I would knit, then when I hit the sweet spot of dampness, I would weave like a fiend until the warp got too dry. Spray. Knit. Weave. Repeat. During the month of August, I wove 6 metres of shirt warp, knit a pair of stockings and a pair of 18th century ladies mitts. My other weaving projects I finished up in July, thank goodness.

My second angel was also a weaver who came into the studio one morning and sat with me for a good part of the day, talking about historical textiles and clothing. She was on her was to the UK to take part in an experimental archaeology conference, meeting a friend who had just done what I was doing. Her friend was recreating Norse textiles, a process far more difficult than what I was undertaking, but close. This new weaver angle asked why I was working at the centre. Did I not have a studio at home? I told her that no, I did not have a loom of my own. She told me that once she was back in Canada she would email me. She had some things she’d like to discuss with me, one of which was a loom.

The Labour Day weekend there was an encampment at the Halifax Citadel. I spent the entire weekend at the encampment, in historic dress, constructing historical clothing. That weekend I got most of one shirt made. I finished it up on the Tuesday at home, and Tuesday evening, with great hesitation, I put the shirt in the wash. With so much starch, the shirt felt as if it were made of cardboard. I had to mount my portion of the final exhibit on Wednesday for the opening on Thursday night. I figured at that point, if the linen completely self-destructed in the wash, I’d have a fun story to tell during the opening. The shirt survived the wash though, and the exhibit was a success. It was the very first time any of my work had been placed in a gallery exhibit. I was excited and happy with my work.

At this point, I realize that this has become a wordy post. There are things that I needed to tell you though, so that the problems could be discussed fully. I’ll start by telling you that at the beginning, I wove both dish towelling and dish cloths. They were woven using the same warp, the same threading of the loom. I changed the weave structure of the cloth by changing how I tied-up my pedals underneath the loom, and the steps I took to weave. So if looking at the pattern of the weave, the top bar was the same for both types of cloth. What changed was the top right hand corner, and the bar along the right hand side. This made the difference between a waffle pattern for the dish cloths, and a bird’s eye twill for the towelling. This project went perfectly from start to finish. My chair strapping also went perfectly. The tablecloth didn’t make it past winding the warp on the back of the loom because this is where things started to go wrong with my shirt warp. In all, I had four looms on the go that summer.

And so the shirt warp. Going back to problem #1, you may notice that the threads were drying out. This was due to the fact that I was working in an air conditioned space. A space where I could not turn the air conditioning off. Air conditioning works by drawing the moisture out of the air. It also drew the moisture out of my threads. Problem #2, my having to constantly starch the thread lead to there being far too much starch on the thread. This lead to the cardboard quality of the fabric, but also may have, most likely had, contributed to the looseness of the weave structure. No matter how much I beat the weft threads into the course before, I could not get the fabric to weave tightly enough. The resulting fabric has a characteristic of cheesecloth, only really heavy cheesecloth. Reducing the size of the weft threads might help negate this issue. I am planning to try with the remainder of the shirt warp, once I get back to weaving again.

Problem #3 came from how I was taught to wind a warp on to the back beam of a loom. I was taught to use paper between each course of winding, to separate the threads. The studio used cardboard, which was waffled in the middle. This waffling lead to the cardboard collapsing, which I had learned on another warp, and so with the shirt warp, I went back to paper. Because the warp was so long, and so wide, the paper could not handle the task of keeping the threads neat and tidy. My shirt warp slid off the edges of the paper. Angel #1 told me that I should be using sticks to separate the warp. That wood will not collapse, and will hold the threads properly. The studio was full of sticks, as you use pairs of them to keep threads separate in the back of the heddle harnesses.

Angel #2 returned from the UK and did email me. It turns out that she was a sheep farmer, and a weaver. When she bought her current farm, she found an older model, colonial box loom from LeClerc. She had several looms already, and would I like to have this loom? My family and I drove up to her farm, spending the afternoon with her before bringing my loom home to Halifax. While there I learned about the sheep she bred. How those heritage breed sheep were black when they were young, and then as they got older, they turned white. This would start me thinking about what I had learned about Norse clothing years before. I also learned that she has waste warps on her looms, that run from the back beam through the heddles and reeds, and that she ties her warp threads to these waste threads to making threading much faster. Since most of what she weaves is similar in threading, she just reused the waste threads over and over again. Each loom had a different threading.

That winter, Ross Farm museum had a flax production day. Garth and my family decided we needed to attend. We learned about how flax is grown, harvested and processed into fibres and then spun into linen thread. Garth and I both were able to spin for a bit, and I learned that I could get a far finer thread with my very limited background in spinning than I ever could buy.

This trip also got me thinking about the ‘when’ of how fibres are processed, and how this may influence textile production. When you really begin to think about the ‘when’ of things, it starts to make sense how the problems arose in my own production. Linen is harvested in the Fall, it is then laid out to basically rot in the sun and the rain, separating the fibres from the reed it grew as. These fibres are then spun in the early winter months, and fabric can be woven in the wettest period of our year in Nova Scotia, the late winter. Sheep are sheared in the spring, and the fibres are spun then and weaving this fibre may happen in the late spring, when the weather begins to dry up, but it is still not hot. Summer months are for sowing, caring for and harvesting crops. There is usually not enough time in the day to be spinning or weaving cloth, but there may be time to sew clothing. In fact, the summer months are my most favourite times to sew, as my hands stay nice and warm, making it easier to hold the needle.

The time of year, coupled with the problem of the air conditioning made for an uncomfortable summer of textile production for me. I knew how to weave. I knew how to reproduce the patterns from the historical text. Until I encountered the issues that I had with the shirt warp though, I did not fully grasp all of the concepts of historical textile production. The difference between the “knowing how’ and ‘knowing that’; skill and knowledge going their separate ways” (Kramer and Bredekamp, 2013, p. 26). In the Siegert article, the author tells us that ‘cultural techniques always have to take account of what they exclude” (Siegert, 2013, p. 62). There was a lot that was not taken into account with the historical text, the least of which was the assumption that I would have had a firm enough background in weaving to know that I should not be weaving in the hot or dry conditions. I am now a firm believer in the importance of practice based research, in that I would not have fully understood the research I had undertaken to that point if I had not taken into consideration the daily practices of farming and producing textiles myself. I will never again have air conditioning in my studio. I will be mindful of the tasks I complete and the time of year. In the future, I also hope to grow my own flax and produce my own threads to weave with, so that I may have a better understanding of how much clothing is ‘worth’. That first shirt project was meant to study the production of cloth into shirt, and then how long that shirt would last through wearing. I know now, that the shirt will not last as long as a more tightly woven cloth would. The looseness of the weave structure is already producing stress points that will contribute to the wearing out of the shirt. We will see if I can get a tighter weave structure out or future attempts with the remaining warp threads. I hope so.

Works Cited

Bredekamp, S. K. (2013). Culture, Technology, Cultural Techniques – Moving Beyond Text1. Theory Culture Society, 20-29.

Bronson, J. a. (1977). Early American Weaving and Dyeing: The Domestic Manufacturer’s Assistant and Family Directory in the Arts of Weaving and Dyeing. New York: Dover.

Dixon, A. (2007). The Handweaver’s Pattern Directory. Loveland CO: Interweave Press.

Siegert, B. (2013). Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory. Theory, Culture and Society, 48-65.

Sterne, J. (2003). Bourdieu, Technique and Technology. Cultural Studies, 367-389.

The post Weaving as Cultural Practice: What time of the year is it? appeared first on &.

]]>The post Author and Authority: Creating Fashion Trends in Historical Re-enacting (Probe on Foucault’s ‘Author’) appeared first on &.

]]>As I begin my own process towards authorship, I have been thinking a great deal on how we create authorities out of persons who share their research. This has held exceptional resonance with me in my own work on Eighteenth Century fashion and how it is viewed by the community of re-enactors I belong to. When I began as a historical interpreter and costumer, I knew about the larger community, but did not feel a part of it. In Nova Scotia, we were a small group who did our own research and shared it with our friends, discussing and shaping ideas within a very small group (at that time, about 100 total members). With the dawn of the internet, and social media beginning with email list serves, our scope grew larger, we were now included within the larger, North American community. At that time, there were few opportunities for non-academics to publish their research. Some were able to write and publish books about and through their own local museum collections, others published articles in community newsletters. At that time, the status of the author rose to dizzying heights, they became superstars within the community and began to be noticed by the academic community. The research they published was copied extensively throughout the larger North American community with little regard to situational and cultural dynamics.

Fashion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but neither does it exist as a wide spread phenomena. Even today, there are cultural differences in how we dress ourselves, even here in Canada. The cut of our jeans will be different in Nova Scotia than it is in Alberta, not only because our bodies are differently shaped but also because of how we wear clothing culturally. These differences relate to genetics, weather patterns, religion, and culture. In the 18th century, those cultural differences can be highly insular. What a person wore in Pennsylvania Deutch country would be different than what a Protestant Loyalist refugee would have worn on their way from New Jersey to Nova Scotia. Don’t get me wrong, fashion existed, and was not as stagnant as would first appear, but there are cultural, weather, situational, and religious differences at play. A person interpreting a figure from Nova Scotian history cannot just copy an outfit from ‘Fitting and Proper’ (Burnston, 2000) and be entirely correct.

Since the publication of this book, Sharon Burnston has become an authority on 18th century clothing. She has been given star status within the community. Others who achieved such status through early publication were not as considerate in their research though, and that research has proven to not be as reliable as Burnston’s book. Other books published in the same time frame include ‘Costume Close Up: Clothing Construction and Pattern, 1750-1790’ (Baumgarten, 1999), ‘Whatever Shall I Wear’ (Riley, 2002), and ‘Tidings from the Eighteenth Century’ (Gilgun, 1993). All these authors achieved star status, or authority, save for Mara Riley, despite her research being considerate and strong.

Each of these publications created fashion trends within the hobby. How can this be, when members of the community should be considering the context of the research and how it relates to their own interpretations of historical figures? It seems that modern capitalism and desire can influence how we interpret histories, and that when a woman wants a new dress, what is new and ‘fashionable’, even in research, can sway a decision in what the seamstress creates. Through our actions, we in the community have given authority to these authors. The fact that some hold higher status as authors than others may have a lot to do with the status of the publication, the paper used in the printing, the institution that houses the collection studied, the use of colour, even the gloss used. When we look at the collections of garments studied themselves, are there photographs taken, or were artist’s drawings used? What was the quality and care given to the renderings? Are patterns included? Are they easy to use? Are the garments themselves stunning to the eye, or are they very plain-Jane? All of these considerations will make or break a fashion trend, or create authority for the author. And so, with each publication, copies of the fashions that were published appeared at re-enactment events across the Eastern Seaboard, whether they were appropriate for the interpretation or not.

In the intervening years, more and more research has been published. Members of the community have been actively working with museums and in academia, and the research and scholarship has grown stronger with each author. Through online communities, care has been taken to ensure that people are interpreting their historical figures with considerations of time, place, culture, religion, and political status. And yet, fashion trends continue.

When Neal Hurst’s Bachelor’s Honors thesis was published, Hurst was working in the men’s tailoring shop at Colonial Williamsburg. Entitled ‘Kind of Armour, being peculiar to America: The American Hunting Shirt’ (Hurst, 2013), the paper set off a flurry of men wanting to own hunting shirts. Were they appropriate to all walks of life? All areas of North America? These were important questions that needed to be reflected upon before having a seamstress or tailor create one for a given interpretation. Hurst’s authority on the subject is well earned though, as this was not a simple undergraduate thesis. Hurst has the academic and employment credentials to back up his research, and that paper was well documented and written. Even he will exclaim though, that this garment is not appropriate for everyone in the hobby, and he would cringe if it were to become a fashionable trend in the community.

Neal Hurst with Will Gore, both wearing versions of the Hunting Shirt

Neal Hurst with Will Gore, both wearing versions of the Hunting Shirt

With ladies wear, these trends can be even more drastic. The men in our community, for the most part, belong to military units that have fairly strict codes of dress. Uniforms can be researched and recreated to the year, month, even the battle. Women, because they are a civilian population, do not have such restrictions, and so follow fashionable trends a bit more closely. Fashion trends that are regularly brought to mind include items like silk bonnets, printed cotton jackets, stripes, silk gowns, and brightly coloured or printed gowns. When each of these items listed comes into fashion within the community, or comes around again as fashionable in the community, questions of authenticity follow. Who would have worn these items? How would they have been worn? Is that printed cotton originally a bed hanging (upholstery fabric), or was is the lining on the hem of a quilted petticoat? What class/culture would have worn that garment? And even, is that fabric appearing to be too 1980s instead of 1780s? Who first wears a new style has influence on how it will become a fashion trend. Do they have authority? Have they been published? Do they have name fame? These are all considerations when considering a fashion trend within the hobby. Recently, a young woman in New England has entered the hobby, and quickly developed a following. She was well turned out from her very first event. Jennifer Wilbur studied fashion photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology (academic word fame amoung fashion people). Her clothing and interpretation is well researched and thought out. She seeks out talented individuals to create her wardrobe, even spending top dollar for historically accurate shoes from the UK that many longtime community members are hard pressed to consider. Even though her wardrobe reflects that of a lower situational Loyalist woman on the march with the army, I suspect she too will create a fashion trend amoung women in the hobby. She is considered an ‘authentic’ or ‘progressive’ member of the community, names given to ‘fashionable’ young people in the organization that are pushing research and interpretation beyond the comfort levels of the older generation.

Jennifer Wilbur, Loyalist woman on the march: One of her first events

Jennifer Wilbur, Loyalist woman on the march: One of her first events

So as I embark on my own explorations in the fashion of the 18th century, I am considering my own authorship, my own authenticity, and my own word fame. Amoung my smaller provincial group, I have long been considered ‘progressive’ with regards to the clothing I create and wear. Will this name fame be carried over into the larger North American community? How will my own research hold up, to scrutiny and to time? I will have to consider carefully my reader. I will also have to consider the extant pieces I will chose to include in the published document, were they a fashion ‘trend’ of their time? An anomaly, or widely worn? What was the cultural, class, religious, and political ramifications behind the garment, if any? I will also have to consider how my research is published. Will I choose a high gloss paper, a hard cover or paper back, colour photographs or the original garments, or line drawings? How will all of this play a role in how authentic my research is viewed, and how enduring it will become? Will I have the authority to speak and be heard?

The Author: Kelly Arlene Grant

The Author: Kelly Arlene Grant

Works Cited

Burnston, S. A. (2000). Fitting and Proper. Scurlock Pub Co .

Foucault, M. (1980). What is an Author. In Lanuage, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (1998). On the Ways of Writing History. In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984 (pp. 279-96). New York: New Press.

Gilgun, B. (1993). Tidings from the Eighteenth Century. Scurlock Pub Co.

Hurst, N. (2013). Kind of Armour, being peculiar to America: The American Hunting Shirt. Williamsburg Virginia: College of William and Mary.

Linda Baumgarten, J. W. (1999). Costume Close Up: Clothing Construction and Pattern, 1750-1790. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Riley, M. (2002). Whatever Shall I Wear? A Guide to Assembling a Woman’s Basic 18th century Wardrobe. Graphics and Fine Arts Press.

The post Author and Authority: Creating Fashion Trends in Historical Re-enacting (Probe on Foucault’s ‘Author’) appeared first on &.

]]>