The post Workshop Facilitation and Transient ‘Space’: An Interview appeared first on &.

]]>When my initial interviewee (someone with a large amount of involvement and a fairly high position in anti-oppression education) had to back out part way through, my immediate reaction was to panic. Then, I remembered that, actually, even if they didn’t have particular titles, there were many people around me who had been engaged in this type of work and who had interacted with the transient ‘space’ of the workshop many times over. Luckily enough, one of these friends was kind enough to sit down with me and talk about it.

Ffionn M: As I’ve mentioned, the general theme of these interview assignments is “the lab” or spaces of knowledge production. When we got the assignment, my interest was immediately pulled in the direction of ‘spaces’ that were a little more fluid, knowledge productions that occupied a physical ‘space’ for only a short period but also transformed it into a very distinct sort of space of its own. That’s why I’ve asked you to come talk to me about — broadly defined, here, as ‘social justice’ — workshop and discussion facilitation.

To start, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your experiences facilitating workshops (what organizations, what sorts of workshops, where they were held, what led you to become a facilitator, etc.).

Theo K: Well, I first started getting involved with Queer McGill after being elected as one of the communications admins. I ended up getting very involved with Queer Concordia, the Union for Gender Empowerment at McGill, and the Centre for Gender Advocacy at Concordia as part of my communications officer duties. That was when I started getting into facilitating groups and leading discussions in general. Especially after my transition and becoming one of the only trans admins on the QM board, I was trained in Trans 101 workshops with the UGE that I facilitated for QM workshop events as well as admin safe space training programs. I ran the Trans 101 for safe space training for QC executives and volunteers as well. I also facilitated for discussion groups fairly often. Most of these were usually held in the QM office or the SSMU(mcgill student union) building’s bookable meeting spaces, or the QC office- usually spaces on campus run by students. Later on, after I’d stepped off the QM board and became more involved with the CGA, I volunteered to be trained as a facilitator for plans made by Concordia to have mandatory consent workshops in the first year residences; these plans ultimately fell through, and we were deployed to facilitate smaller workshops at Concordia’s Arts and Science frosh. I also became a facilitator for Trans Concordia for a brief period, facilitating discussion groups in the CGA meeting space generously lent to us.

FM: You mention that you were trained to facilitate Trans 101 workshops after you transitioned and became one of the only trans administrators on the Queer McGill Board of Directors. It sounds as though the responsibility fell on you because you were trans. Did it feel like that? Did that affect the way you were able to facilitate Trans 101 workshops in that space?

From your description, it also seems like this was the first type of workshop you were trained to facilitate. How do you think your own experience (personal knowledge) related to you being trained in this sort of facilitation? When you were learning to facilitate and later when you were facilitating these workshops, what sorts of knowledges do you feel you were bringing to the table and engaging with?

TK: Yes and no; Queer McGill, and a lot of queer campus resources that were student-run tend to have a bad rep in terms of being trans-friendly because of the fact that they tend to lean more towards social events, like parties. I took it upon myself when I transitioned to facilitate the workshops, since I felt that I was the only one with the depth of personal knowledge to do it, but in hindsight, I feel as though I was expected to do just that. I suppose that’s just the way it goes; people always expect the one who would benefit most from an endeavor of spreading knowledge to be the one to work hardest at doing so. Also on the flipside, being the only trans admin also gave me a sense of authority when facilitating workshops, of course. There’s a certain sort of understanding that if you’re a cis person coming to a trans 101, you’re not going to know better than the trans guy running it.

Being trans doesn’t mean that you’d know everything there is to know about trans politics, though (believe me, there are many trans folks who are still quite unaware). Of course I would have to have had training, and being involved in the construction of the actual workshop was quite enlightening as well- I was part of revamping the trans 101 that the UGE has, and I learned a lot about gender politics during that. I guess I think that being trans simply helped me make more sense of it, or gave me a perspective that is capable of a deeper understanding of gender politics than those who don’t have to live the complications of it. Improvising during a facilitation to counter questions or disagreements is also a skill that facilitators are trained in, and that deeper understanding helps immensely.

FM: I think that’s an interesting tension — that because you belong to the marginalized group, you are expected to be the bearer of knowledge but, at the same time, in certain ‘spaces,’ it also grants you a level of authority. Were there any times where you felt these two forces come into conflict in a facilitation space (or in life in general, since these ideas tend to continue outside of workshop spaces as well)?

You also mention the importance of being able to improvise during a workshop. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about this — how it comes up, how your deeper understanding of particular issues helps, what ideas those participators are bringing to the table and what it all results in.

TK: There’s never really a conflict so much as the two conflating to become taxing situations. Of course there’s the incidents that all trans people (and all marginalized people, for their respective marginalizations, for that matter) are weary of- cis people simply expecting to be educated, though they may even be resistant to this knowledge, and assuming that their journey to enlightenment is our responsibility. I usually come to workshops with the energy and expectation to deal with this, but the worst I guess is when it happens outside of workshops, in my daily life, or in my personal internet presence on social media or some such. I don’t think many people actually understand the mental labour that goes into coaxing someone to understand something new. Of course, sometimes I’m deemed too close to the issue to really be objective about it, and my authority on the matter is undermined that way- it’s a bit of a paradox. Usually employed by people who have no intention of understanding, but rather proving to themselves that they tried and that they were ultimately right.

In terms of improvising, there are always questions that ask for things not covered in the workshop. Usually I try to share a consensus with my fellow facilitators if I have any, about whether we could go over the question, or it would open up a discussion much more advanced than a 101 and that we need to skip for time concerns. Having a deeper understanding of the material helps us decide these things, or improvise ways of answering exactly what the person attending may be confused about in a short amount of time.

FM: I hear that! I have definitely, in my own experience with facilitation, noticed that there is a huge difference in the types of dialogues that are produced when you have folks who want to be better about an issue and folks who think that they’re already in the right. It’s also almost always (in my experience) the latter who expect you to educate them outside of the workshop space, at their whim — I think, maybe, those attitudes go hand-in-hand.

It’s interesting to think about this sort of participator in terms of the ‘space’ concept I mentioned at the beginning, though, as well. Maybe the lack of distinct physical space for workshops gives this type of participator the (incredibly misinformed) idea that any encounter with a marginalized person or an educator of this type is, itself, a site for facilitation? Further, what other effects do you think the temporary quality of physical spaces might have on workshop environments or how workshops and discussions are conducted?

TK: Well, the part where people just seem to expect education from marginalized people comes from a fundamental lack of empathy, in my opinion. I usually attribute it to a kind of ‘mental space’: everyone makes different mental spaces for different encounters. When with a friend, you’d make a mental space of friendliness or familiarity, or when dealing with an acquaintance you’d make a mental space of politeness or distance: I’ve found that a lot of cis or white people have treated me as if I’m some sort of kiosk (laugh). I think that there’s some sort of part where who I am (queer, poc) compromises any mental state that they would make while talking to me.

It’s actually something I’ve found because workshop spaces have such a transient nature to them- it’s usually a club office, or a rented meeting space at a restaurant/cafe. There are no assigned places for workshops the way there are for lectures or meetings, so the actual workshop space is a sort of… collective mental one that you join in on when you enter a workshop. The facilitators set the rules and boundaries for the meeting at the start of the session, and these rules hold until the end; I’m not entirely decided yet on whether or not this has a positive or negative effect on the workshop experience and endeavor in general. On one hand, the construction of the mental space makes for attendees that are more engaged and remember more; on the other, it might take away from the perceived legitimacy of the session, and consequently, the information presented in the session. I’ve found that it helps bring a more casual air to workshops, where people feel comfortable asking questions but also understand the deeply personal nature of some of the politics that are being discussed.

FM: I think a mind ‘space’ is exactly what it is. And this creation of ‘workshop’ environment in terms of the written and unwritten rules of behaviour is exactly what changes the physical space into a workshop or discussion space for a short time. How have these mind spaces met with the physical spaces in the past? Have there been particularly fruitful meetings of environment/space? have there ever been particularly poor spaces? Have the physical spaces or what might have been going on around the workshop ever ‘intruded,’ so to speak, on the workshop? If so, what was the result?

TK: I mean, spaces that can be closed off from the general public are always better. There have always been smaller interruptions, especially when the space is one that’s usually used for something else: club rooms always have someone or another coming by for something, and the SSMU general space in particular always has other students and other clubs making noise. A common interruption is when someone steps into a club room, unaware that it’s a workshop space at the moment, and the facilitators end up having to explain to them what’s going on; they either stay or leave, but the bewilderedness of finding the space reappropriated to something they weren’t expecting is still present. That’s essentially what workshops have been like for me so far- reappropriating a physical space with a mind space. The problem is when using an open space that other people already have a mental space of before the workshop space is constructed.

I remember a safe space training workshop that was held in the SSMU general; I wasn’t facilitating, but I was familiar with the material and the facilitators. We were seated around a table at the far end of the space, when somebody else, a tall white dude sat at the table and interrupted to ask what was happening. The facilitators had to re-draw the rules and boundaries for the newcomer, a bit sloppily because of time constraints, and I could feel a shift in the space to a palpably uncomfortable one that was particularly difficult for the facilitators. He kept asking questions about things that had been covered before he had arrived and taking up more time and space. The mind space of the workshop had been compromised, even though the workshop was open to everyone, this sudden interruption made the facilitators lose grasp over the space somewhat.

I’ve always enjoyed the workshops and discussions I’ve facilitated in the more closed spaces for this reason, I suppose. When I was working with the Concordia groups more extensively later on, the CGA lent us a room to use, that was upstairs in a Concordia building with a door that closed and locked. It was spacious enough to hold a good amount of people, and made for a more intimate, let’s say, environment where a certain safe space and facilitator’s authority was able to be held but people would still feel free to contribute or ask questions.

FM: I guess, in that way, you do need physical spaces that can at least work with the ‘space’ of a workshop, rather than against it. The story you told is an interesting one in terms of those rules of behaviour I mentioned earlier but also in terms of audience. I mean, I think that it is 100% the job of the privileged group to seek out knowledge, rather than the oppressed group constantly trying to provide it, but there is a tendency with workshop environments to have a certain participator in mind and it does make for a lot of familiar faces and fewer new ones, depending on the type of facilitation/discussion you’re running. Part of this could very well be due to the transient nature of the physical spaces, which makes things less accessible, but I also think that there are a lot of people who just aren’t willing to participate in this sort of knowledge production, aren’t interested in entering the mind ‘space’ of the workshop. What do you think about this problem? Do you see it as a problem? What can or should be done, in your opinion? Also, do you think that this sort of issue of audience is the same across the board for the different sorts of anti-oppression workshops you’ve run or do you think there are differences and, if so, why?

TK: Well, I guess it mostly comes down to an issue of mental and emotional labour. Of course there are going to be more belligerent attendees, and the amount of effort that it takes to deal with them aren’t necessarily fair to ask from facilitators who are of marginalized groups, whose knowledge runs a risk of being deemed too ‘subjective’ by these attendees. My personal opinion is that more privileged allies should be involved with workshops- those who can listen and help the marginalized facilitator speak from their depth of understanding, while being the one who doesn’t have to put in as much effort and is not at as much risk as the marginalized facilitator when dealing with a more resistant audience.

The knowledge being produced for an audience in a workshop is a very constructed and thought-out process designed to open up a discourse in every attendee’s life- interruptions are accounted for, and actually often lead to very interesting discussions (once during a trans 101 a discussion on preferred pronouns that hadn’t been part of the workshop was opened up and was very involved and enlightening) but it only works when the space has a clear respect for the facilitator, and subsequently for the process of knowledge production being brought to the session.

It’s a bit of a dilemma, I guess. I’ve been to many a workshop where it was simply me, the facilitator, and a bunch of people already involved with the cause and frankly didn’t need the workshop. I definitely think workshops need to reach a broader audience and those outside of the organizing groups, but that runs the risk of having attendees like the tall guy I mentioned. In an optimal world, facilitators would always be paired with one who is part of the marginalized group being taught about and one very adamant ally to sort of verbally wrassle down some of the more problematic attendees (laugh). Workshops for social justice issues still tend to be very small-scale efforts with little funding- as I mentioned earlier, Concordia had plans to integrate mandatory consent workshops for first years in the residences that fell through- and levels of security, safety, and authority are slippery things to maintain without bigger forces to back us up. And even with official sanction, it tends to become difficult to reach people with a workshop- I remember my first year in undergrad having a mandatory dorm workshop on various issues near the beginning of the year. I heard many complaints from my floormates before and after the workshop, and even found people skipping it because they found it ‘stupid’ and ‘unnecessary’ (which is quite inaccurate given the rate of sexual assault in dorms and, speaking from personal experience, the disregard for my queerness or pronouns). I very much appreciated that the RA for my floor was very strict about attendance, and felt that it did create an environment where I felt safer talking about and pointing out bad experiences than it could have been.

So. There’s no concrete solution I’ve come across yet, but I guess it comes down to that- more vigilant allyship from people and organizations in positions of power and authority.

The post Workshop Facilitation and Transient ‘Space’: An Interview appeared first on &.

]]>The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

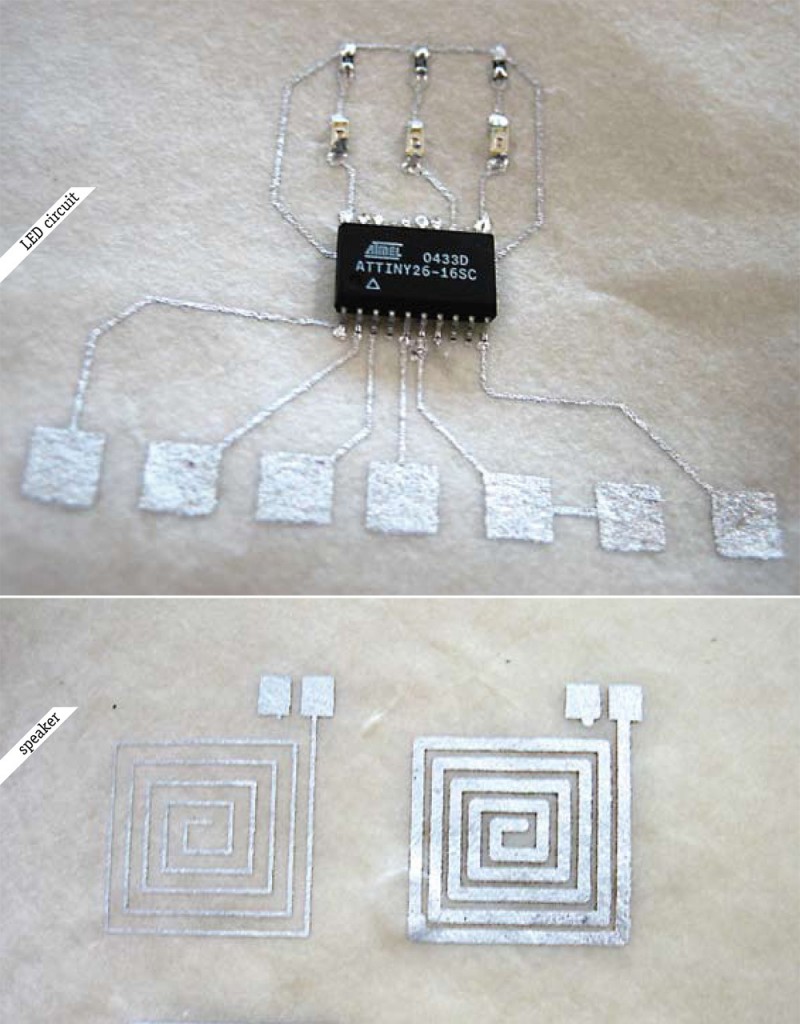

]]>Joanna Berzowska founded XS Labs in 2002 at Concordia, where they focus on “the development and design of electronic textiles, responsive clothing, wearable technologies, reactive materials, and squishy interfaces.” Previous to XS Labs, Berzowska studied and worked at the MIT Media Lab, and she co-founded International Fashion Machines with Maggie Orth. She holds a BA in Pure Mathematics and a BFA in Design Arts.

The kind of work that Berzowska engages in is profoundly interdisciplinary and crosses distinctions that we might automatically put up between design, industry, art, and theory. Her work has been shown at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the V&A in London, and at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, among others. Her lab at Concordia is located on the 10th floor of the EV and is part of the textiles cluster.

I met Joanna Berzowska for a coffee in St. Henri on December 10 to discuss wearable technology, her experience working at the MIT Media Lab, the agency of things, and what she believes is important for building an interdisciplinary space.

First of all, why do you call XS Labs a “lab”? Instead of say a “studio”? With International Fashion Machines, for example, I notice they call themselves a “company” — why “lab”?

I think part of the reason I originally called it a lab was just out of habit, because I was at the MIT Lab, and “lab” implies a kind of research culture… I’m thinking about it right now, because I guess I’ve never thought about it in depth… So part two of my answer is that it was a very direct, easy way of referencing research culture. Part three is a very strong emphasis at the time — when I was hired by Concordia fourteen years ago — to re-brand the institution as a research institution as opposed to a teaching institution. So when I was hired, I was basically told, your teaching doesn’t matter, your service doesn’t matter, all that matters is your research and how much money you raise. I think it was a turning point for the university, it was like the institution swung one way, because very strongly it was trying to position itself as a viable research institution at the time. Since then, the pendulum has really swung the other way. Now I think with the new president, Alan Shepard, he’s trying to find a comfortable middle that supports research as well as entrepreneurship, but at the same time recognizes that Concordia will never be a pure research institution and that’s what Alan always says — we can’t compete with McGill, we can’t compete with Ivy League–type schools, Concordia is unique. But when I was hired, the push was really, for a year or two, it’s all about research. So that’s part three of my answer, which is political in a sense. Going back to part two, it was important that “lab” reference research culture in a direct way, especially being in the Fine Arts, where, at that time, all the funding bodies and all of the potential sources of research income did not recognize what we now call “research-creation” as a viable way of working.

What’s interesting is I originally called it “XS Labs,” and even within that there’s an embedded critique. “XS” official stands for “Extra Soft” and it’s about soft circuits, it’s about soft electronics, but of course when you read it, it also sounds like “excess,” so there’s an embedded critique of a kind of contrast between a lot of research in Humanities, which is inherently critical of how we apply technology or how society embraces new changes, and then research in let’s say the sciences or Engineering, which don’t question it as much, but really just pursues innovation. The reason I chose the word “XS” was to have this critique. A lot of what I’m doing is in Engineering, science-type research, and we’re just going to put as much electronics as we can into all of these textiles and wearables, but, being in the Fine Arts, I’m also aware that we have to do so in a very deliberative, interrogative way, and question it at each step of the way. So that’s very much the tradition of XS Labs. And also, since XS Labs started, it’s XS Labs, colon, and what comes after the colon has evolved. So now I do refer to it as a design research studio. I’ve examined every couple of years the kind of work that we do, and these days I call it a design research studio, but the name is still XS Labs, so I guess I just want it all [laughs].

You’ve worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group. This semester we’ve read a bit of Stewart Brand and have talked about California ideology and its very utopian take on technology. I read in an interview with you [with Jake Moore] where you were talking about researchers such as [Steve] Mann or [Hiroshi] Ishii who work with wearable technology in a way where it’s an exoskeleton or a kind of protective layer. And I was wondering if “Extra Soft” is a response to this kind of ethos that came out of working with the Media Lab and this situation where technology is celebrated as utopic and where wearable technology is something protective.

Yeah. So at the Media Lab there was definitely a strong gender divide actually, between how wearables were tackled by male researchers — and also, maybe coincidentally, the female researchers had more of a background in design or the arts. These are all stereotypes, which unfortunately were instantiated in my experience. So, women who I worked with, like Elise Co, Maggie Orth, who was my business partner for a while, Amanda Parkers, who came later, who’s now very active in the space, and then the dudes that I worked with, who were Brad Rhodes, Thad Starner, who ended up working for Google Glass, and Steve Mann, who’s a prof now at U of T [University of Toronto] — the women had more of a design and art background. I’m not saying it’s necessarily because of gender that they were more in touch with embodied sorts of questions, perhaps it was because of their past training, but maybe the past training was tied to gender. There was in fact one woman who was a really hardcore engineer, she still is, and she worked with Ros Picard [Rosalind W. Picard], who’s also a woman and also a hardcore engineer, so maybe the background training is more relevant in terms of the women that I worked with who were more interested in what we now refer to as embodied interaction, and considering the body as crucial — they were interested in textiles and the surface of the skin and what I now call beyond-the-wrist interaction —

Beyond the wrist…?

Whereas the dudes were really interested in things that you can manipulate with your hands and head-mounted displays, I was more interested in what happens on the rest of the body. And in many ways what happens on the rest of the body can be considered as dirty or sexual or smelly or provocative, so that doesn’t fit as easily into an Engineering research model, where you don’t have a specific problem to solve. And of course there are many problems, like how do you track baby kicks during a pregnancy, or whatever [laughs]. But, I certainly was more interested in the textiles, the rest of the body, how can we embed computation in textiles rather than attach devices to our bodies. And one corollary of that is also an interest in simpler kinds of computation. So, you know, the more cyborg approach to wearable computing basically strives to develop a computer as powerful as possible that is wearable and portable and now we have them [points to phone recording conversation] — these phones are kind of that, right? So, keep in mind this was twenty years ago, and the idea was, how can we take our computer with us all over the place? And now we do it with our phones, it’s funny. But back then, it was basically, you had to put the hard drive in the backpack, you have to take it all in pieces, have a huge antenna for your satellite GPS, etc. That’s wearable computing very literally, where you wear the same kind of computer that you have on your desk, whereas with my electronic textiles and the soft computation, it wasn’t a computer as you know it from your desk, but computation, how can you have wearable computing that is about simple kinds of interactions or simple kinds of functionality that are more interested perhaps in well-being or pleasure or just everyday experience or communication rather than just taking your computer from your office. That’s where the Extra Soft comes from, and there’s so many references, because also there’s hard science versus soft science.

It also sometimes seems like a lot of wearable technology aims to be “corrective” somehow, but you’re not really trying to “correct” the body. You’re trying to do something different.

“Extend” is usually what I say, whatever that means. Or not bring about some huge productivity gain or something but instead allow us to experience the world in a slightly different way.

To go back to the lab for a minute, is XS Labs one lab space or is it a series of lab spaces now in the EV?

Going back to the lab I realized there was something else that I wanted to say, so I’m glad you brought it up again. Another reason why I called it a “lab” is also that I wanted another way of working with my students. Traditionally in the Fine Arts when you work with grad students, they work on their own individual projects and you maybe advise them, you provide critique, whereas in the sciences and Engineering, they’re research assistants and you pay them for their time and they work not on your project but on a group project. I remember when I first came I was always using the plural “we” even though I only had maybe one research assistant, and people were very surprised, they were like, why aren’t you saying “I” or “my work,” and it’s because I was coming from a research lab culture, where every research paper that’s published has multiple authors, and you don’t work alone, ever, so that was another reason why I wanted to call it a “lab” and to train the students that I hired to not think of it as a job but to think of it as a collective inquiry that everybody will be credited for and everybody will benefit from. There were a lot of issues that we came up against of course where there was confusion between what would be their own individual practice and what is the research lab practice, so I tried to have very specific guidelines around how we credit, what people can take credit for, and how everybody had to credit everybody else’s work, and that’s a whole other kind of discussion.

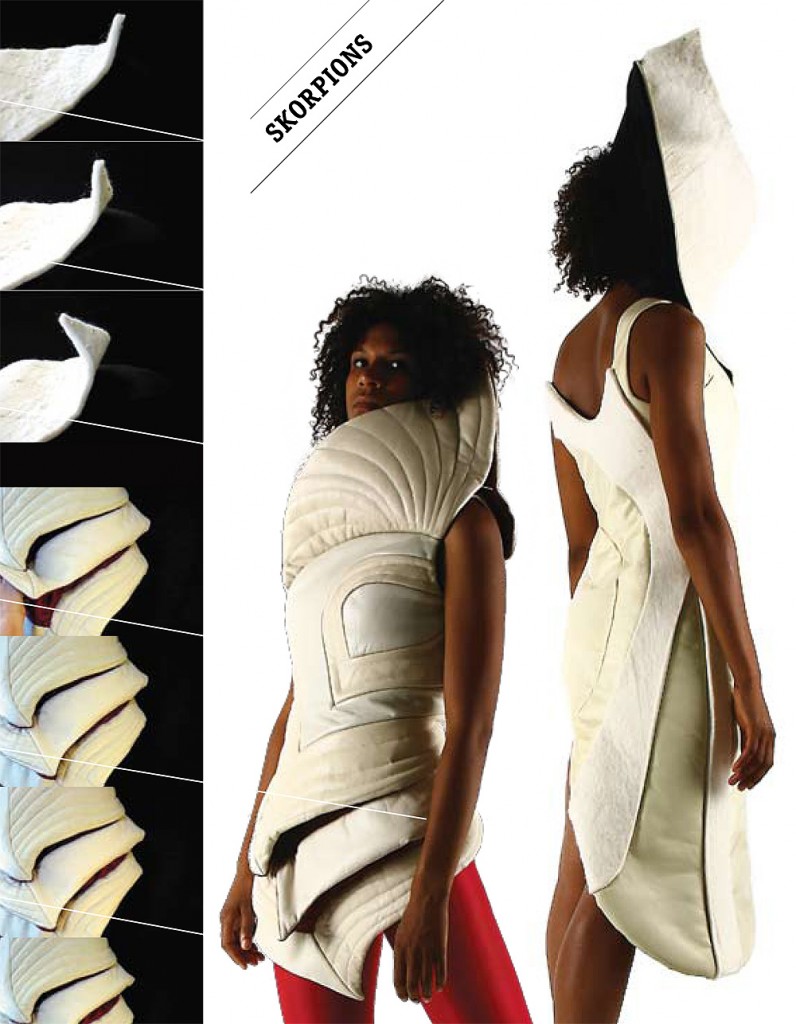

In terms of physical space, we’ve always had one space that’s shifted over the last fifteen years, that’s smaller or larger, that was like our headquarters. Then through Hexagram and other facilities we needed to use or have access to other spaces either through the more technical work we needed to do, like the weaving, or, at one point, I was collaborating with a prof in Materials Science on Nitinol, so we had all of these other spaces where work was done, mostly leveraging specific facilities and expertise. With Materials Science we needed specific furnaces to shape the Nitinol and quench it. We’ve got different kinds of looms or laser cutters. Or, collaborating with École Polytechnique, we’ve had some of our students there developing new fibres. But we’ve always had this little central headquarters. [Nitinol, “also known as muscle wire, is a shape memory alloy (SMA) of nickel and titanium that has the ability to indefinitely remember its geometry”; it is used, for example, in XS Lab’s Skorpions dress.]

When you yourself go into the lab, do you have any daily rituals that you find yourself performing there?

I’ll just say that I was Chair of the department for three years and now I’m on sabbatical and I’m pregnant, so what I do now does not reflect historically. Maybe I’ll just talk about the previous ten years, when there was a strong routine and a strong practice. I always had my days organized — certain days I devoted to teaching and office hours — certain days to service — meaning all the committee work, etc., and all of the research assistants who worked with me, some of them were grad students, some of them were undergrads, some of them were affiliates, there was really a wide range of different ways that I worked with students and research assistants. We had one weekly meeting, where everybody was expected to attend. So that was a sort of ritual where we’d touch base and I would give goals and guidance to everybody for the week. I also had somewhat of a hierarchical structure, where students who had been there longer would be responsible for training some of the younger students, and by younger I don’t mean age, but the newer ones. A lot of the culture in a research lab isn’t about hiring skilled personnel, it’s about training HQP [Highly Qualified Personnel], that’s what we write in the grant proposals [laughs]. So I hire students with potential who don’t necessarily have the skills that I want them to have, and part of what we do is train them. I would pay them to take workshops or classes, but I would also really expect them to teach one another and I would hire very complementary kinds of personalities who could teach each other, and the work is intrinsically interdisciplinary, which is where I think you’re going with this anyway. So that kind of collaboration was really crucial to the success of the work.

I’m very interested in research-creation. Would you say there’s any divide in your work between the research and the creation? Do you have a space more for inspiration and a separate theoretical component, or is that tied together for you?

It’s really tied together because the creation is about questioning technology and doing things with technology that were not possible in the past. So for me, creation is not about what colour is it — let’s talk about garments since we make a lot of those — it was never really about, what does the garment look like — it is, what would it mean to have a garment that moved on your body and moved in an uncomfortable way? What would it mean to have a garment that needs energy but doesn’t have batteries and needs to harness energy from the environment or from somebody else’s body. So for me that’s the creative aspect, and then being able to formulate that into a research question that leads to a successful research grant proposal. And then, working with a team that is very creative, so that the potential answers to these questions that we suggest can be described as beautiful or evocative or playful. And they do get invited to be shown in galleries and museums, which I guess is sort of the institutional stamp of approval for the creation side. I’m not an artist. I’ve never had a solo show as an artist. I really think of myself much more as a researcher. But a big part of my dissemination happens in museums and galleries.

So you wouldn’t consider yourself an artist, but you show in galleries? And your inspiration is not so much connected to the fashion, but connected to questions about technology?

Yes. Like how can we really break down what a garment is. Or what a textile is. And how can we use all of these emerging materials that are being used in aerospace or the automobile industries or whatever, but use them in garments. What kinds of new functionalities would they enable? New forms of expression. New ways of connecting with one another. But also, how would they help us understand the world in a different way? Question the world. The project Caption Electric and Battery Boy is really about questioning our dependence on energy and batteries and portables. The major point there was to create garments that are sort of ridiculous and uncomfortable. And the thematic that runs through it is one of fear and paranoia and fear of natural disasters and protection, so it’s deeply linked. And then in order for me to be able to raise the money that I’ve raised that’s more from the sciences and Engineering, there’s always a very strong scientific or engineering innovation in the project. And I would feel like a fraud if there weren’t.

Do you think with working on very highly funded projects, with industry and with big labels, do you see that as in any way compromising your vision? Or extending it? Do you find that working with big industries provides a positive constraint or something where you have to really compromise your creative work?

It’s a different kind of vision. I don’t see them as contradictory. The obstacle to work in my experience has just been the really kind of overwhelming bureaucratic aspect of administering large research grants at the university, where I ended up just spending so much of my money doing paper work and filing reports and filing expense reports in a thoroughly inefficient way… Industry can’t afford to have the same kind of level of inefficiency that we have in academia… They would go out of business. So that’s super refreshing. Of course then we have a board of directors that we have to answer to. We have to show a business model that would be profitable with an X amount of years. Whether that business model involves being acquired by Google or having sales or whatever, I mean that’s another questions, it’s the VC [Venture Capital] world.

That’s interesting, because usually we see the academy as the place where we can sort of nurture our bigger ideas and industry as a place where we have to compromise. But that’s not your experience?

It’s different ideas. But what’s really exciting is there’s different kinds of industry. And right now with the start-up culture around new technology, it’s all about innovation and wonder and discovery that, sure, you have to have a business model, but that can be viewed as a benefit rather than an impediment… I’ve also worked on projects with creative studios. So industry doesn’t necessarily mean military or medical devices. Industry can also mean Cirque du Soleil. Or working with PixMob, which is a great company, some of my ex students started it. So industry, sure, has to have a business model, and if it’s not profitable, it will go out of business, but it doesn’t mean you don’t innovate or you don’t do exciting work. And sometimes innovation is actually stifled in academia because of all the bureaucracy and paper work. I’m being provocative of course. Because all of the assumptions you’re bringing to that question are true, but there’s also that other side.

You said you don’t see yourself as an artist. What do you think the differences are between art and design?

Everybody is going to give you a different answer. But my answer these days is that art is about one individual and design is about multiple individuals. And of course people will argue with that and I will change my mind eventually, but that’s how I think about it these days. So for me, design fits a lot better into this research model where we have multiple authors for each project. It’s almost like thinking of the research work as a theatre performance, or a play, or an orchestra, where you have a conductor, but then everybody gets credited for their own role. Whereas I find a lot of the art research-creation, it’s still about the one person who takes credit for everything even though they might have a team of people working with them. But also for me design is perhaps a little bit more concerned with the tools, the materials, the processes, rather than like the final moment of showing the piece.

So in design there’s more of a process?

No, it’s not that there is more process, but the process is almost more important than the final piece, for me, okay. Whereas the way that I think of art is that the final artefact is given more importance, culturally. In design research, the process, the materials, the steps you took, are maybe just as important or even more important. And especially when you look at that whole movement of speculative design. Or critical design coming out of the UK, with people like Dunne & Raby. In fact, there isn’t really a final outcome, but it’s all about these trajectories and interrogations and asking “what if?” and showing these speculative processes. Or experimenting with materials. But not necessarily building up to the one artefact that will go into a permanent collection somewhere.

But say with industry you would need to eventually produce an artefact—

—Yeah, you need a product—

—Or else they would be like, “where’s your product”—

Well not necessarily, because also patents are a very viable outcome of industry work. So I’m writing a lot of patents right now with OmSignal. And those aren’t artefacts. That’s IP [intellectual property] that has a high monetary value.

In your work, for example in your Skorpions dress, you describe the dress as parasitic and the wearer as a host, so a lot of agency is given to the actual items that you create. Do you see what you do as somehow aligned with biotech? These garments are almost coming “alive”?

To me, a lot of interaction design I find problematic around the idea that the human is always in control or needs to always be in control versus the idea of giving up control a little bit. And maybe that’s also just a personal philosophy as well. With being a mother. Raising two kids in this very unusual sort of circumstance where I’m not their biological mother but I’m their full-time mother and yet I don’t have the same kind of control… So I think for me, my personal life experience has also influenced the way that I think about interaction design… It’s less about biotech and more about control.

It sounds a little like actor-network theory. We read this also in communication with Stewart Brand. And the fact that objects or technology can dictate the way things go, not necessarily just the human.

One of my favourite quotes from Sherry Turkle is that computers aren’t just a projective medium, but also a constructive medium [See Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (New York: Simon and Schuster), 1984]. You control or project your desires on them, but they also shape what your desires are.

So it’s a collaboration in a way between the human and the technology? And this is maybe freeing?

Well, the reason I can do these things is that I’m not in an Engineering faculty where each project has to be about solving a specific problem that is then quantifiably successful or unsuccessful. I can produce these projects that exist in this much more qualitative research space, whatever that means. I don’t have to have tables and graphs for each project that I make…. I don’t need to do those kinds of quantitative studies for my research, which allows me to explore these questions that are more — sometimes I say they’re poetic — I don’t have a very rigid theoretical structure for how I talk about these things. But it’s definitely great to have a freedom not to need a quantifiable result at the end of each project.

Is there anything about your lab that you would like to change or that you find problematic? Say, in terms of space?

When we were in that corner space on the 10th floor, that was too small. At one point if you can imagine I had about twelve people working in there with all kinds of sewing machines and electronic stations, so that was nuts. The thing that makes a space successful is to allow everybody to feel ownership over a portion of the space. You need everybody to feel like some small portion of it is their own. To develop a level of trust where people can leave things without worrying about them being either stolen physically or the ideas stolen, so actually working on a culture of collaboration and trust is really important. Definitely in my particular discipline where we need machines there’s always going to be the need to go to other spaces to use different kinds of specialized machines or facilities. But the space itself — it’s more about the culture you create in the space, about exchange, about giving, and the way that I fostered that from the very beginning is by having a lot of parties and 5à7s. It’s all about building trust.

All images taken from the XS Labs catalogue.

The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>The post Environmental Humanities: Engaging Critics in an Interdisciplinary Space appeared first on &.

]]>Studies of the environment have a history of being characterized by a deep division between scientific research and humanities scholarship. In the same way, literary ecocriticism has been engrained within a critical lineage associated with an American wilderness ethic and Jeffersonian logic of “culture” in opposition to “the environment.” In conversation with anti-making discourses, that Debbie Chachra uses in her article for The Atlantic “Why I Am Not a Maker,” this probe will consider the interdisciplinary space set up in environmental studies—where the “real” is never far from “theories”—to discuss an academic journal that has privileged an integration of humanities research methods in environment studies that is decentering, destabilizing and enriching the field.

In the most recent issue of Environmental Humanities, a journal that publishes interdisciplinary research on the environment, scholars from across the disciplines were invited to respond to An Ecomodernist Manifesto (2015), a recently published article that argues for “decoupling human development from environmental impacts” (7). Characterized by the journal’s editors as “one of the more concrete and explicit statements to have emerged out of a broader effort to reconfigure what counts as environmentalism in the early decades of the 21st century,” the Manifesto generated a variety of responses from humanities scholars. Among them, figured Bruno Latour, who, in “Fifty Shades of Green,” compares the manifesto’s message to the invention of the electronic cigarette to say that the Manifesto might have found a way to “be modern and ecological without either of the two” (220). Far from a non sequitur, Latour uses the association to discuss “ecomodernism” as a concept, to challenge the manifesto’s claims within a sociological framework.

Everyone of you here who knows anything about controversies regarding human and non-human entities entangled together are fully aware that there is not one single case where it is useful to make the distinction between what is “natural” and what “is not natural.” [. . .] “Nature” isolated from its twin sister “culture” is a phantom of Western anthropology. What we are dealing with instead are distributions of agencies in which we are all entangled in ways which are highly controversial and the reactions to which are almost always highly counterintuitive. Or to put it in my language, the world is not made of “matters of fact” but rather “matters of concern.” “Nature is but a name for excess.” (Latour 221)

Latour’s integration of actor-network theory into a discussion of environmentalism to challenge “matters of fact” cuts to the heart of the project of Environmental Humanities: to provide a discursive space that “draws humanities disciplines into conversation with each other, and with the natural and social sciences” and allow discussion to move beyond the entrenched dualism of science and humanities research that has pervaded environment studies (Rose et al. 2). In the introduction to the journal’s inaugural issue, “Thinking Through the Environment, Unsettling the Humanities,” the editors describe the publication as a project with two aspects:

[. . .], on the one hand, the common focus of the humanities on critique and an ‘unsettling’ of dominant narratives, and on the other, the dire need for all peoples to be constructively involved in helping to shape better possibilities in these dark times. The environmental humanities is necessarily, therefore, an effort to inhabit a difficult space of simultaneous critique and action. (Rose et al. 3)

This articulation of Environmental Humanities, as a “space of simultaneous critique and action,” interpellates discourses of critical making. In his discussion of critical making as a conceptual and material process, Matt Ratto describes a practice that bridges “a deeper disconnect between conceptual understandings of technology and our material experiences with them” (253).

The use of the term critical making to describe our work signals a desire to theoretically and pragmatically connect two modes of engagement with the world that are often held separate—critical thinking, typically understood as conceptually and linguistically based, and physical “making,” goal-based material work. (Ratto 253)

In the same way, the contributors of Environmental Humanities reconcile a disciplinary disconnect between science and the humanities through an impetus to be relevant to contemporary environmental concerns. Like the collaborative space that Ratto describes, the journal’s emphasis on publishing scholarship intended for an interdisciplinary audience (written outside of established sub-fields of Environmental Humanities like environmental history or environmental philosophy) provides a space that “encourages the development of a collective frame while allowing disciplinary and epistemic differences to be both highlighted and hopefully overcome” (Ratto 253). However, the comparison between critical making and environmental humanities relies on equating the work of humanities scholars with that of the developers and designers from which Ratto derives his ideas. Which begs the question—

What do the humanists—as educators, critics and theorists—bring to the table?

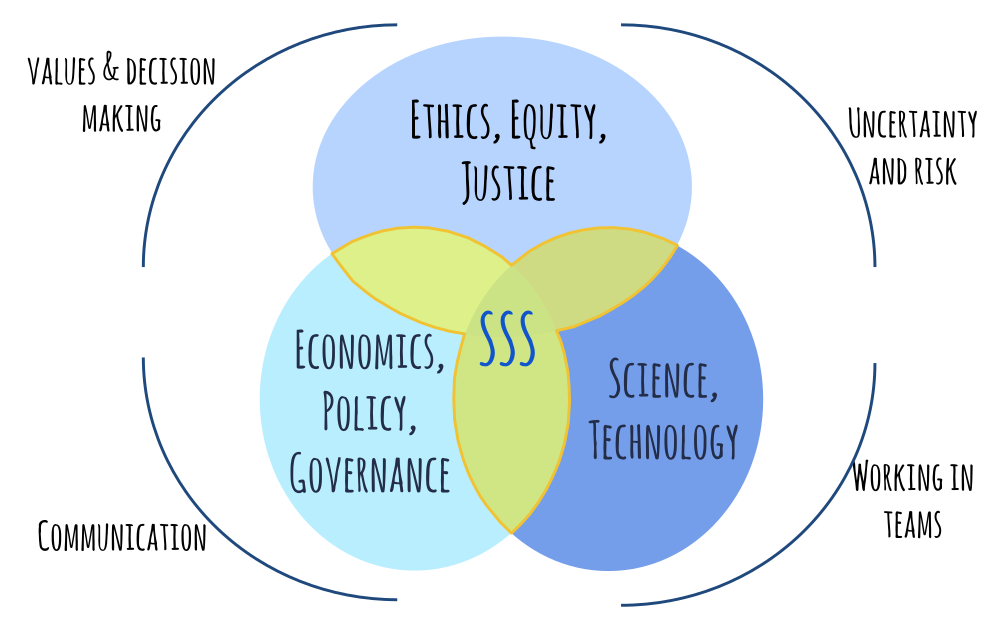

This graph, taken from the McGill University’s Sustainability, Science and Society program page—an interdisciplinary and interfaculty degree program that allows students to work in both science and the humanities—demonstrates they articulate as the three pillars of an interdisciplinary approach to studying the environment: science and technology; economics, policy and governance; and ethics, equity and justice. In a program designed to educate students in both current scientific research and critical discourse so they can affect environmental policy, this degree program seems to perform the “active” aspect of Environmental Humanities’ project: “to be constructively involved in helping to shape better possibilities in these dark times” (Rose et al. 3). Or, be relevant.

But if relevancy were the only driving force of research in the Humanities, Literature departments would be much smaller and devote their funding towards teaching Language and Composition, rather than give classes on old media, theories of happiness and a handful of postcolonial novelists that (almost) no one has ever heard of.

The primacy of relevancy in our society that privileges “making” and “producing” objects is a mind-set that characterizes the humanities, and their work in environment studies, “as a ‘non-science’, with the primary role of mediating between the natural sciences and ‘the public’. [. . .] at the core of these approaches is an impoverished and narrow conceptualisation of human agency, social and cultural formation, social change and the entangled relations between human and non-human worlds” (Rose et al. 2). However, the scholarship that the journal promotes is not based on interdisciplinary studies as an amalgamation of disciplines. In the same way that Latour challenges An Ecomodernist Manifesto’s understanding of “modern” and “environment,” interdisciplinary publications like Environmental Humanities challenge our understanding of the “humanities” by providing a space for scholars to circumvent the limitations of disciplinary approaches and perceived notions of the environment. Beyond an amalgamation of various disciplinary practices, interdisciplinarity in this case enriches critical thinking on the environment:

The humanities have traditionally worked with questions of meaning, value, ethics, justice and the politics of knowledge production. In bringing these questions into environmental domains, we are able to articulate a ‘thicker’ notion of humanity, one that rejects reductionist accounts of self-contained, rational, decision making subjects. Rather, the environmental humanities positions us as participants in lively ecologies of meaning and value, entangled within rich patterns of cultural and historical diversity that shape who we are and the ways in which we are able to ‘become with’ others. At the core of this approach is a focus on the underlying cultural and philosophical frameworks that are entangled with the ways in which diverse human cultures have made themselves at home in a more than human world. (Rose et al. 2)

The value in this type of thinking is that it isn’t entrenched in a single field or publication. Certain areas of study are emerging within established fields, like postcolonial ecocriticism in literary studies, that challenge our understanding of the interactions between humans and the non-human world. In the case of postcolonial ecocriticism, postcolonial theory is being used to revitalize and diversify ecocriticism’s traditionally American literary canon through the study of the treatment of the environment in texts written in the Global South, to give “environmental literary studies an international dimension” (Nixon 239). Decentering the study of environmental themes in literature allows postcolonial theorists to call into question “the perception that environmentalism is chiefly a politics that protects urban social privilege” (DeLoughrey 26).

One of the key themes of postcolonial ecocriticism is the use of imagination to articulate alternate relationships to the non-human world. In her essay on Amitav Ghosh’s novel The Hungry Tide, Laura White discusses Ghosh’s use of the novel form to develop “a rhythmic pattern of organization that reflects nonvisual ways of knowing the Sunderbans and that positions the novel as an alternative way of knowing which disrupts colonial and neocolonial visions of the Sunderbans by narrating interactions between geohistorically located and embodied knowers” (514-15). For Ghosh, only the broad form of the novel can “create ways of imagining human-nature relations and new ways of making environmental decisions” (517). In “The Greater Common Good,” a political essay published in 1999 on the human cost of monumental water development projects in India, novelist Arundhati Roy questions the “narrative of national development” that portrays infrastructure development as central to the nation’s interest, even as development creates developmental refugees that are “unimagined” from the nation’s “imagined community” (Nixon “Unimagined Communities” 150). In these texts, “imagination” (narrative, representation and subjectivity) is used to constitute place-based engagements with the non-human world, and “complicate” dominant ways of knowing and understanding the environment.

This approach to thinking about the border between the human and the non-human, through postcolonial literature’s engagement with environment, is only made possible in a space where literary scholars are in conversation with sociologists, anthropologists, environmental scientists and all the other actors involved in ecocriticism. In the same way that critical making, as a mode of exploration and articulation, allowed students at the Umea Institute of Design to develop ideas (Ratto 254), the interplay and exchange of ideas and critical perspectives between theorists of different disciplines studying the environment has allowed for alternate configurations of the border between human and non-human, cultures and environments, to be articulated. In the case of Environmental Humanities, this exchange was made possible within an interdisciplinary space that understood the critical value of Humanities research in its own right.

Cover Image: Taken from the cover of Environmental Humanities 7, which is available for you to read here. Image by Glendon Rolston “Spiderwebs Everwhere”.

Works Cited

Asafu-Adjaye, John et al. An Ecomodernist Manifesto. www.ecomodernism.org, April 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2015.

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic. Web. Accessed 24. Nov 2015.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth and George B. Handley. “Introduction: Towards an Aesthetics of the Earth.” Postcolonial Ecologies: Literatures of the Environment. London: Oxford UP, 2011.

Latour, Bruno. “Fifty Shades of Green.” Environmental Humanities 7 (2015): pp. 219-225.

McGill University. “What Knowledge and Skills Are Needed for Solving Sustainability Challenges?” <www.mcgill.ca/sss/> Web. Accessed 25. Nov 2015.

Nixon, Rob. “Environmentalism and Postcolonialism.” Postcolonial Studies and Beyond. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2005.

Nixon, Rob. “Unimagined Communities: Megadams, Monumental Modernity and Developmental Refugees.” Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Boston: Harvard UP, 2011.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society: An International Journal 27.4 (2011): pp. 252-260.

Rose, Deborah Bird et al. “Thinking Through the Environment, Unsettling the Humanities.” Environmental Humanities 1 (2012): pp. 1-5.

Roy, Arundhati. “The Greater Common Good.” The Cost of Living. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1999.

White, Laura. “Novel Visions: Seeing the Sunderbans through Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20 (2013): pp. 513-531.

The post Environmental Humanities: Engaging Critics in an Interdisciplinary Space appeared first on &.

]]>The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The Webster Library Transformation is underway and in the University’s postings about the work being done, the word ‘renovation’ is conspicuously absent possibly because it carries connotations of disrepair, age and maintenance of an old system. Maybe that’s also why it’s being touted as a “next-generation” library, which makes a kind of avowal of the timeliness of the library but also sounds like the unveiling of a new IPhone.[1] It’s similar to the previous version but somehow entirely life changing, transformative. It should not only bring us into the present age but it should project us into a time beyond our own. The library reprogrammed as scholastic utopia. The language used to describe the library’s changes is utopic in this sense that through innovation we will be taken into a new space, a hitherto imagined space that brings us not only into a different physical location, but projects us into a different conceptual space. I think the choice of the word transformation is apt and that the library will not only change the way we work and produce work as students, but as I would like to explore in this probe, the library transformation reflects and is an articulation of an already occurring shift in the way we conceptualise knowledge, the creation of knowledge and the identity of the student.

The Second floor

My preferred study space has always been the carrels (I prefer ‘cubes’) in the silent reading zone of the second floor along the windows that look down on Bishop street. The carrels are designed for the kind of individual writing work I need to do. The partitions separating each table and chair connect each student but also shields them from each other’s view. The walls act kind of like horse blinders or ‘blinkers’ as they are sometimes called, blocking out potentially distracting stimuli and directing the gaze front and centre. Sometimes I lean forward for maximum immersion or back to escape the feeling that I exist only within a word document. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard’s meditates on corners, describing this type of space fondly as a “half-box, part walls, part door” (137) a space whose construction ensures immobility and allows us to “inhabit with intensity.”(xxxviii) Bachelard claims that the only we learn how to do this by occupying these corner spaces where imagination is seemingly everything. For me this silent, ascetic method of work and student has been part of the identity of an English student. But it can also be isolating. I wonder if my work sometimes reflects the circuitous trains of thought going on in my conceptual space or the narrowness of my work space. In I wonder if I am ‘blinkered’. I can’t help but think there is something like this going on when I am cloistered in my cubicle with my texts and my lecture notes trying to construct something of value. If the texts, the tech and the Profs are actors that influence our work then why not the spaces we produce our work in as well? In looking at the library transformation I began to see how a complex set of relations between people, objects, space and time can perform or express ideological work that informs the academic work being done at the University.

“Space that has been seized by the imagination cannot remain indifferent space subject to the measures and estimates of the surveyor.” (Bachelard, xxxvi)

The Third Floor

As I entered the new floor of the Webster library I was sceptical, I liked my claustrophobic little cube. I had only seen digital projections of a modern looking near-bookless library populated with ghostly students. Going up to the third floor was an ambivalent experience. I couldn’t help but be struck by the vast improvement in overall aesthetics of the third floor. The lighting was bright but soft, the lines of the furniture and shelves clean and new and the colors were not stale and drained of life. And yet the territory is slightly bewildering. Walking through the library I noticed the main difference between the second and third floor is a more open concept which gives the feeling of spaciousness although the study spaces are as close or closer together than in some areas of the second floor. Maybe this is an illusory distinction caused by the partitions in the old carrels, which have the effect of creating a bunch of little microcosms of student space. The library transformation was borne partially from a crisis of space, so it will be interesting to see how the individual, somewhat bulky space of the carrel is re-imagined.[2] This ties in with the second big difference: visibility. On the third floor you are always visible to everyone around you. The room is bounded by two glassed-in silent reading rooms with completely open tables. The workspaces are individual but communal at the same time. In between these rooms there is an open concept study area with ikeaesque tables, chairs and sofas. Talking is permitted, some students work alone along the wall looking down into the library building and others work in groups around the tables writing figures on a whiteboard. In the middle of the room there are three big glass rooms that resemble aquariums that contain groups of students working together.

For the library to do the work of a library, it must be constructed around clear delimitations. The different configurations of space must prescribe different types of behaviour. The more ingeniously these spaces are designed, the less visible the work being performed becomes.[3] The traditional library job of shushing has transformed from a slightly Orwellian image of a woman pressing her finger to her lips to an androgynous grinning emoji type symbol. Library Special Projects Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and informed me that next to space two of the biggest concerns of the project was improving light and addressing noise. Concordia even hired an acoustician to find out how to promote a quiet space. The ingenuity of this floor is that in addressing the issue of light by replacing walls with glass, the visibility of the students seems to make them more prone to self-monitoring their noise levels. Even in the collaboration space students speak in hushed tones.

In “Of Other Spaces” Foucault describes sanctification of space as “inviolable” oppositions embedded in the space itself. These oppositions of silence and noise, inside and outside, together and separate are of paramount importance to the library and the new floor’s construction makes us those (almost) perfect little door closers. I would argue that the quality of a library depends upon its status as a somewhat sacred space, where these rituals of work, these “rites and purifications” (26) have to be observed to occupy the space and make way for the production of knowledge. “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing which both isolates them and makes them penetrable.”(26) The visibility of the student at all times allows us to perceive the needs of the other student and our own interest in respecting them by being silent. When the walls of the carrels are removed, we do the work of the walls. The design of the room demands that we keep out of each other’s workspace.[4] Transparency has also been a factor in the construction of the new library spaces through the Webster Library Transformation Blog. Students are now more aware of the changes made in the configuration of space while it is happening and encourage student input. This is also indicative of the kind of student of the new library, simultaneously and seamlessly utilizing virtual and physical space and making them communicate and improve upon each other.

Perhaps this new mode of thinking and producing transparently betrays the movement from one kind of student to another, but also another way of seeing the pre-existing connections between ideas, people, disciplines and techniques that can encourage innovation and understanding. Transparency could do away with the opportunities for glitches to hide in the system, to do away with biases of knowledge and make it easier to revise and critique our thinking. In Star’s “The Ethnography of Infrastructure” we have seen how transparency is arrived at through failure of the system and crisis. The library transformation came about partly from a crisis of space but also made visible the infrastructure of knowledge production. The transformation is also an opportunity for each tiny decision to nurture and influence the changing academic environment in its uncertain and hybrid form.

“In the everyday world, it is of shattered, scattered sacredness that we must speak […]” -Marc Augé, “An Ethnologist in the Metro.”

Naming is also important to note. The reading rooms in the third floor are named after countries namely, Kenya, France, Netherlands, Vietnam and India. In Marc Augé’s study of the Paris metro he notes the way that the historical names of the metro stops have shifting significations for different users and generations of users.[5] The naming of the reading rooms eschews the local in favour of the global. Library Special Project Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and explained that the choice of countries corresponds to research done on the cultural backgrounds of the student population at Concordia. She also mentioned that the naming has not gone unnoticed by students and they’ve taken to referring to the rooms by their international names. This is indicative not only of the diversity of the students but also of the widening of scope from the local, historical to the global and mobile. The West is potentially dethroned as the priveledged centre of knowledge production. Foucault argues that “The museum and the library are heterotopias proper to Western culture of the nineteenth century.” (26), however the twenty first century sees the access to that wealth of knowledge broadened by our access via digital archives which makes us mobile, living libraries. At the same time that certain rites have to be performed to utilize the space, there is a corresponding de-sacralization of the library as site of knowledge. A corresponding change in physical access to books may be coming as the library aims to make more space for student. That student also occupies a different kind of space emerging from the individual space of the lone genius to the public and social space of the “next-generation” library. There is no arcane knowledge in this space, or rather it has lost its position of power in favour of the everyday as the cultural ground shifts, hierarchies of knowledge slip, high and low culture is renegotiated. Moreover the process of how these valuations of knowledge come to be is made visible and studied. This change in the conception of knowledge might mean the disappearance of a certain type of scholar or simply the transformation of his work.

“In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.” –Foucault “Of Other Spaces”

The stacks themselves are also a part of the transformation. The collections movement from the second to the third floor necessitated a paring down of the books. The task of ‘weeding’ removes from the collections all redundant, out-dated and damaged books and donating them to an archive or another institution. The out-dated books fascinated me the most, to imagine all the once relevant ideas in those books becoming artefacts is part of the process of knowledge making but still chills me but even to be wrong means one is playing a part in the creation of knowledge and that some can only hope to be a blip on the academic radar.[6]This pruning of material betrays the already apparent role of artefact, the books have been assessed by the decreasing frequency with which they are requested, and their unpopularity pointing to newer modes of thought; their removal is just the solidification of their non-agency. Although the library assures me that they never simply throw out books, I can’t help but wonder if anything is lost in the increasing digitization of documents. Increasingly, students can access information across different mediums and using new tools, which entail a different experience of learning.

The new library has also added two different types of spaces with the express purpose of showing work, The Multipurpose Room and the Visualization Room. Both rooms provide students with the use of equipment and space designed to share their projects. The inclusion of this room speaks to the imperative to have our work be visible so that others can interact with it. The use of a variety of techniques that crosses disciplines, allows different disciplines to perceive existing connections between areas of study. We see this at work in the MLab, as the different tools and theoretical lenses used take Joyce’s Ulysses beyond the English Lit stacks and seminars. It also speaks to the benefit of visibility in academia through the diffusion of work on blogs and social media. Once mostly a tool for mediating our personal lives, the growing authority of these types of forums allows work to traverse boundaries of academic prestige, defy categories of discipline and exist in experimental forms. And now to digress to another space…

Ninth Floor, Hall Bldg

An incident in the University’s history elucidates articulations of space, transparency, visibility, infrastructure, technology and access to knowledge.The Computer Centre Incident of 1968 was a student riot incited by allegations of racism directed at six West Indian biology students from a faculty member. After talks degenerated at a Hearing Committee formed to investigate the charges, two hundred students occupied the computer centre in the Hall building. Over the next two weeks negotiations were carried out almost to the point of a compromise but failed just as half the students left the protest, the argument reignited and the remaining one hundred students carried out their threat to destroy the computers, causing extensive damage to the building as well. There are many things that are interesting about this story is the way the public space is contested and shown to be already a part of the political and ideological struggles at the university. The student’s choice to occupy the computer centre and threaten the technology in order to leverage their claims shows that they perceived where value and power was situated spatially in Concordia. What is demoralizing is that they wanted recognition of injustice so badly that they would destroy the very spaces and objects that were integral to their own research and identity as students. This incident resulted in the arrest of students, the eventual reinstatement of the accused faculty member and millions of dollars in damage. The computer lab is still on the ninth floor of the Hall building and no traces of the riot remain but the conflict resulted in the re-organization and institution of student representation and a restructuring of policies and codes that govern university life. Interestingly, the Paris protests were happening at the same time, students occupied the streets and took to turning over cars when they couldn’t get their institutions to cooperate. The ideological changes though not completely effected, can be communicated through violence to space. At the same time, the anarchic violence to space is an attack on an expression of ideology, power and forms of social ordering.

Today space at Concordia is increasingly heterogeneous and political and ideological action is intrinsic to the construction of space. If we look at other spaces in the University, memorials, cafes, corners, thresholds, we can see how structure and design can redistribute power to the students. There are as many struggles, stories and resistances as there are spaces in Concordia. The library transformation’s policy of transparency and ongoing construction gives us the opportunity to contribute our own ideas and opinions. Even better the library is an extension of the classroom; part lab, part experiment, a heterotopia that belongs to everyone and no one.

[1] Webster Library Transformation Blog

[2] “At present, only .57 m2 of space is allocated for each full-time equivalent (FTE) student. This ranks as the lowest space per FTE among comparable Quebec and Canadian university libraries.”[2] https://library.concordia.ca/about/transformation/

[3] See Star’s The Ethnology of Infrastructure.

[4] Law, “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.” Concept of strategies of translation improving network strength. (6)

[5] Auge, “An Ethnologist in the Metro” (275)

Works Cited

“Webster Library Transformation.” Libraries. Concordia University, 5 Mar 2015. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Collection Reconfiguration Project: One large step towards a healthy collection.” Webster Library Transformation. Concordia University, 2 Feb 2005. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Our vision for the Webster library.” Concordia University, 19 Nov 2014. JPEG.

“Computer Centre Incident.”Records Management and Archives. Concordia University, Feb 2000. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Augé, Marc. “An Ethnologist in the Metro.” Journal of the Twentieth-Century/Contemporary French Studies.

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958. Print.

Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miscowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” The Johns Hopkins University Press. 16.1 (1986): 22-27. JSTOR. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

Law, John. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.”Center for Science Studies Lancaster University. (1992): 1-11. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Sayers, Jentery. “The Long Now of Ulysses.” Maker Lab in the Humanities. 21 May 2015. Web. 7 Nov 2015.

Star, Susan Leigh. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist. 43 (1999): 377-389. Sage. Web. 2 Nov 2015.

St. Laurent-Taddeo, Brigitte. Personal interview. 11 Nov 2015.

The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Media Lab as a Leather Bar appeared first on &.

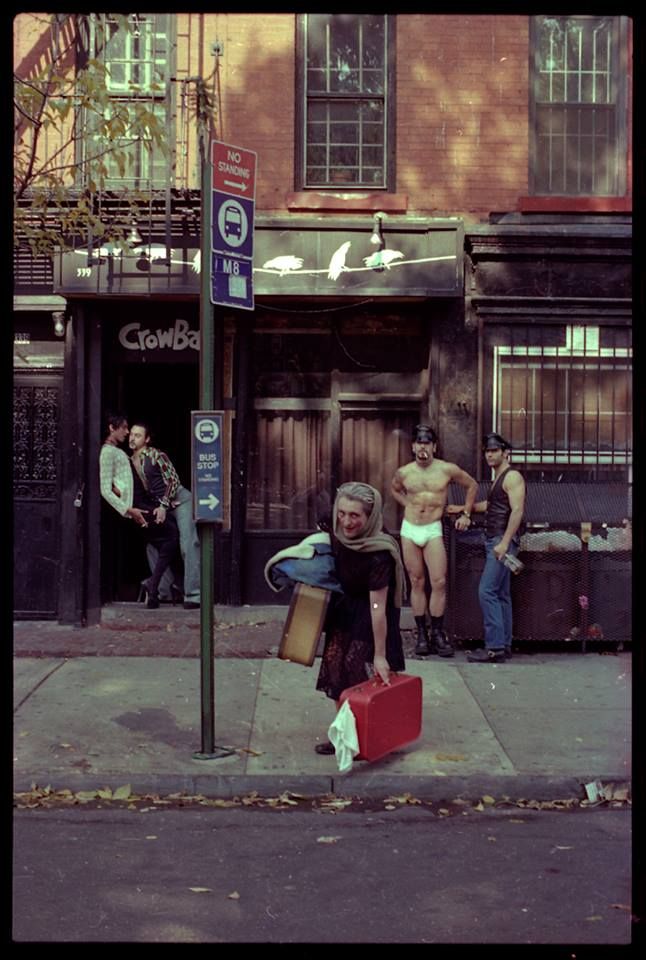

]]>The Village, a Gay Titanic

Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, grounded as it is in our course in the idea of the media lab, made me think of a major concern I have when it comes to my scholarship on city space. Specifically, it made me think of the gay village, and Montreal’s Gay Village in particular, as a kind of utopia, or heterotopia. In her book on Walter Benjamin and The Arcades Project, The Dialectics of Seeing, Susan Buck-Morss writes about the arcade as reflective of bourgeois utopian dreams through its references to commodity fetishism, prostitution, gambling, etc. The gay village is built on a similar kind of utopian idea of safety, freedom, and a particular kind of aesthetics.

Yet, Montreal’s Gay Village is failing. While centrally located and a tourist attraction, especially in the summer, businesses are closing all along Saint Catherine Street, bars are losing their younger patrons and the area is generally seen as less desirable to live in due to violence, homelessness and the economic median. The Village, with its aggressive (yet dwindling) consumerism that certainly defines it as both “gay” and a “village” (bathhouses, sex shops, leather bars, etc.), has become normalized, normativized and boring. Left on the margins of contemporary queer life in the city, I question if the Village might constitute a heterotopia if it fails to be contradictory or disruptive, to be the “other” space that excludes normality while emulating a particular kind of utopia.

Where does the Village fail? In “Of Other Spaces,” Foucault writes of the Middle Ages as a “hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane places […] It was this complete hierarchy, this opposition, this intersection of places that constituted what could very roughly be called medieval space: the space of emplacement” (22). While I would not go as far as to call the Village Medieval, there is something to be said about the fact that, in the absence of a vibrant activist or community-building impulse, the Village has been reduced to that of a shopper, and for this purpose banks on the idea of the “profane.” After all, porn theaters, bathhouses and leather bars are what today’s gay village is. Where it could have been the topsy-turvy place of the carnivalesque, it is not much more than the place of role-play. It is hardly “hetero,” and no one even bothers with the “utopian” part anymore. Certainly, one could speak of the Mile End as an alternative to the village as a reconfiguration of the antiquated idea of “villages” and “ghettos” in a more diverse dress (men, women and others; straights and queers alike), and a space that is queer/heterotopic by default. Otherwise, the dying gay institutions such as the bathhouse, or the YMCA, may betray a sense of heterotopia as deviation and ritual. If we pushed it, today’s village might be heterotopic in a similar way to a cemetery, not only in that it is a dying place, but also in the tradition of gayness as a death of sorts: in her book AIDS Literature and Gay Identity: The Literature of Loss, Monica B. Pearl posited that AIDS was not the first time that “loss, mourning or death” demarcated the gay population, but that it is a part of a larger tradition of interplay between gayness and death, either biological or that of innocence, of the heterosexual identity, of parental/adult authority, or of the natural order” (Pearl 8). Yet, in spite of this macabre, and mythical understanding of the Village, I am still not certain if the Village is the Foucauldian boat for Montreal queers.

The Street Between Four Walls

What of media labs, though? What kind of work can be done in them, especially in terms of urban studies? This is the kind of question that was buzzing around my mind as I thought about the Village as this fixed, inoffensive slice of urban landscape, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the media lab just might be the solution. When, at a round table on media labs, Prof. Darren Wershler spoke of the media lab as heterotopia, both material and imaginary, institutional (relating to, and being funded by a university, for example) and deviant (contained, removed from more traditional modes of knowledge production) (“What Is a Media Lab?”), I kept thinking back of the Village as a mythical project and a much more concretized reality. Would a media lab problematize, or transform, the Village in ways that the Village itself cannot? What would it mean to study the Village at such a distance – both physical and methodological?

If one were to create a media lab based on the study of space, what kind of objects would it contain? Maps, leaflets, flyers, advertisements, street signs, blueprints, coasters with logos of bars underneath… Yet, what would this all do? I am wary of the idea of the database, or the archive – they not only seem so antiquated, but they also seem limited and insular. A media lab, as a think tank, a heterotopia of ideas, objects, and circumstance would have to (re)arrange these artifacts and take them apart like LEGOs in ways that would disrupt and destabilize a place’s accumulated normalcy.