The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>Joanna Berzowska founded XS Labs in 2002 at Concordia, where they focus on “the development and design of electronic textiles, responsive clothing, wearable technologies, reactive materials, and squishy interfaces.” Previous to XS Labs, Berzowska studied and worked at the MIT Media Lab, and she co-founded International Fashion Machines with Maggie Orth. She holds a BA in Pure Mathematics and a BFA in Design Arts.

The kind of work that Berzowska engages in is profoundly interdisciplinary and crosses distinctions that we might automatically put up between design, industry, art, and theory. Her work has been shown at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the V&A in London, and at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, among others. Her lab at Concordia is located on the 10th floor of the EV and is part of the textiles cluster.

I met Joanna Berzowska for a coffee in St. Henri on December 10 to discuss wearable technology, her experience working at the MIT Media Lab, the agency of things, and what she believes is important for building an interdisciplinary space.

First of all, why do you call XS Labs a “lab”? Instead of say a “studio”? With International Fashion Machines, for example, I notice they call themselves a “company” — why “lab”?

I think part of the reason I originally called it a lab was just out of habit, because I was at the MIT Lab, and “lab” implies a kind of research culture… I’m thinking about it right now, because I guess I’ve never thought about it in depth… So part two of my answer is that it was a very direct, easy way of referencing research culture. Part three is a very strong emphasis at the time — when I was hired by Concordia fourteen years ago — to re-brand the institution as a research institution as opposed to a teaching institution. So when I was hired, I was basically told, your teaching doesn’t matter, your service doesn’t matter, all that matters is your research and how much money you raise. I think it was a turning point for the university, it was like the institution swung one way, because very strongly it was trying to position itself as a viable research institution at the time. Since then, the pendulum has really swung the other way. Now I think with the new president, Alan Shepard, he’s trying to find a comfortable middle that supports research as well as entrepreneurship, but at the same time recognizes that Concordia will never be a pure research institution and that’s what Alan always says — we can’t compete with McGill, we can’t compete with Ivy League–type schools, Concordia is unique. But when I was hired, the push was really, for a year or two, it’s all about research. So that’s part three of my answer, which is political in a sense. Going back to part two, it was important that “lab” reference research culture in a direct way, especially being in the Fine Arts, where, at that time, all the funding bodies and all of the potential sources of research income did not recognize what we now call “research-creation” as a viable way of working.

What’s interesting is I originally called it “XS Labs,” and even within that there’s an embedded critique. “XS” official stands for “Extra Soft” and it’s about soft circuits, it’s about soft electronics, but of course when you read it, it also sounds like “excess,” so there’s an embedded critique of a kind of contrast between a lot of research in Humanities, which is inherently critical of how we apply technology or how society embraces new changes, and then research in let’s say the sciences or Engineering, which don’t question it as much, but really just pursues innovation. The reason I chose the word “XS” was to have this critique. A lot of what I’m doing is in Engineering, science-type research, and we’re just going to put as much electronics as we can into all of these textiles and wearables, but, being in the Fine Arts, I’m also aware that we have to do so in a very deliberative, interrogative way, and question it at each step of the way. So that’s very much the tradition of XS Labs. And also, since XS Labs started, it’s XS Labs, colon, and what comes after the colon has evolved. So now I do refer to it as a design research studio. I’ve examined every couple of years the kind of work that we do, and these days I call it a design research studio, but the name is still XS Labs, so I guess I just want it all [laughs].

You’ve worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group. This semester we’ve read a bit of Stewart Brand and have talked about California ideology and its very utopian take on technology. I read in an interview with you [with Jake Moore] where you were talking about researchers such as [Steve] Mann or [Hiroshi] Ishii who work with wearable technology in a way where it’s an exoskeleton or a kind of protective layer. And I was wondering if “Extra Soft” is a response to this kind of ethos that came out of working with the Media Lab and this situation where technology is celebrated as utopic and where wearable technology is something protective.

Yeah. So at the Media Lab there was definitely a strong gender divide actually, between how wearables were tackled by male researchers — and also, maybe coincidentally, the female researchers had more of a background in design or the arts. These are all stereotypes, which unfortunately were instantiated in my experience. So, women who I worked with, like Elise Co, Maggie Orth, who was my business partner for a while, Amanda Parkers, who came later, who’s now very active in the space, and then the dudes that I worked with, who were Brad Rhodes, Thad Starner, who ended up working for Google Glass, and Steve Mann, who’s a prof now at U of T [University of Toronto] — the women had more of a design and art background. I’m not saying it’s necessarily because of gender that they were more in touch with embodied sorts of questions, perhaps it was because of their past training, but maybe the past training was tied to gender. There was in fact one woman who was a really hardcore engineer, she still is, and she worked with Ros Picard [Rosalind W. Picard], who’s also a woman and also a hardcore engineer, so maybe the background training is more relevant in terms of the women that I worked with who were more interested in what we now refer to as embodied interaction, and considering the body as crucial — they were interested in textiles and the surface of the skin and what I now call beyond-the-wrist interaction —

Beyond the wrist…?

Whereas the dudes were really interested in things that you can manipulate with your hands and head-mounted displays, I was more interested in what happens on the rest of the body. And in many ways what happens on the rest of the body can be considered as dirty or sexual or smelly or provocative, so that doesn’t fit as easily into an Engineering research model, where you don’t have a specific problem to solve. And of course there are many problems, like how do you track baby kicks during a pregnancy, or whatever [laughs]. But, I certainly was more interested in the textiles, the rest of the body, how can we embed computation in textiles rather than attach devices to our bodies. And one corollary of that is also an interest in simpler kinds of computation. So, you know, the more cyborg approach to wearable computing basically strives to develop a computer as powerful as possible that is wearable and portable and now we have them [points to phone recording conversation] — these phones are kind of that, right? So, keep in mind this was twenty years ago, and the idea was, how can we take our computer with us all over the place? And now we do it with our phones, it’s funny. But back then, it was basically, you had to put the hard drive in the backpack, you have to take it all in pieces, have a huge antenna for your satellite GPS, etc. That’s wearable computing very literally, where you wear the same kind of computer that you have on your desk, whereas with my electronic textiles and the soft computation, it wasn’t a computer as you know it from your desk, but computation, how can you have wearable computing that is about simple kinds of interactions or simple kinds of functionality that are more interested perhaps in well-being or pleasure or just everyday experience or communication rather than just taking your computer from your office. That’s where the Extra Soft comes from, and there’s so many references, because also there’s hard science versus soft science.

It also sometimes seems like a lot of wearable technology aims to be “corrective” somehow, but you’re not really trying to “correct” the body. You’re trying to do something different.

“Extend” is usually what I say, whatever that means. Or not bring about some huge productivity gain or something but instead allow us to experience the world in a slightly different way.

To go back to the lab for a minute, is XS Labs one lab space or is it a series of lab spaces now in the EV?

Going back to the lab I realized there was something else that I wanted to say, so I’m glad you brought it up again. Another reason why I called it a “lab” is also that I wanted another way of working with my students. Traditionally in the Fine Arts when you work with grad students, they work on their own individual projects and you maybe advise them, you provide critique, whereas in the sciences and Engineering, they’re research assistants and you pay them for their time and they work not on your project but on a group project. I remember when I first came I was always using the plural “we” even though I only had maybe one research assistant, and people were very surprised, they were like, why aren’t you saying “I” or “my work,” and it’s because I was coming from a research lab culture, where every research paper that’s published has multiple authors, and you don’t work alone, ever, so that was another reason why I wanted to call it a “lab” and to train the students that I hired to not think of it as a job but to think of it as a collective inquiry that everybody will be credited for and everybody will benefit from. There were a lot of issues that we came up against of course where there was confusion between what would be their own individual practice and what is the research lab practice, so I tried to have very specific guidelines around how we credit, what people can take credit for, and how everybody had to credit everybody else’s work, and that’s a whole other kind of discussion.

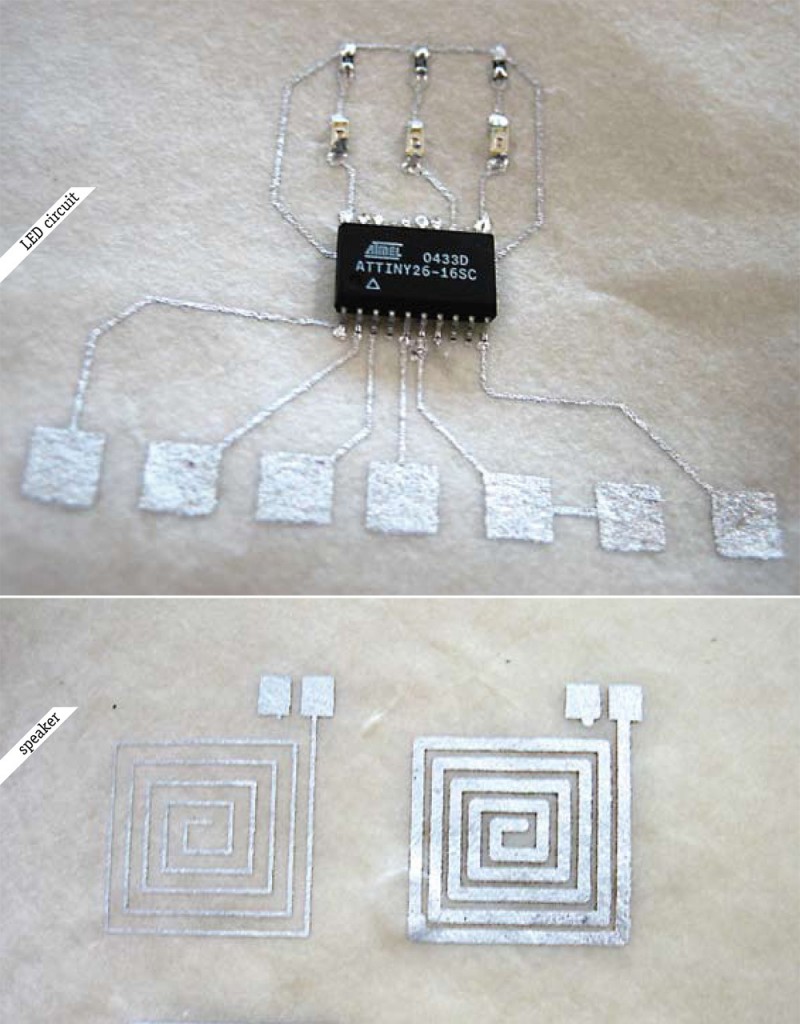

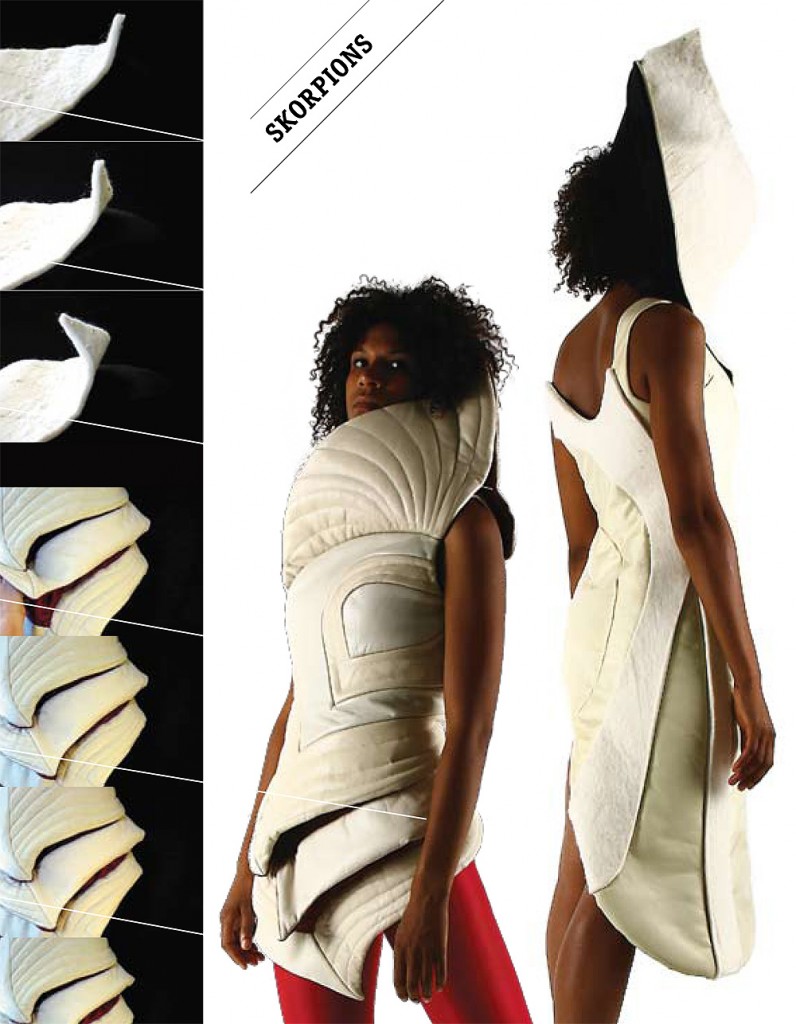

In terms of physical space, we’ve always had one space that’s shifted over the last fifteen years, that’s smaller or larger, that was like our headquarters. Then through Hexagram and other facilities we needed to use or have access to other spaces either through the more technical work we needed to do, like the weaving, or, at one point, I was collaborating with a prof in Materials Science on Nitinol, so we had all of these other spaces where work was done, mostly leveraging specific facilities and expertise. With Materials Science we needed specific furnaces to shape the Nitinol and quench it. We’ve got different kinds of looms or laser cutters. Or, collaborating with École Polytechnique, we’ve had some of our students there developing new fibres. But we’ve always had this little central headquarters. [Nitinol, “also known as muscle wire, is a shape memory alloy (SMA) of nickel and titanium that has the ability to indefinitely remember its geometry”; it is used, for example, in XS Lab’s Skorpions dress.]

When you yourself go into the lab, do you have any daily rituals that you find yourself performing there?

I’ll just say that I was Chair of the department for three years and now I’m on sabbatical and I’m pregnant, so what I do now does not reflect historically. Maybe I’ll just talk about the previous ten years, when there was a strong routine and a strong practice. I always had my days organized — certain days I devoted to teaching and office hours — certain days to service — meaning all the committee work, etc., and all of the research assistants who worked with me, some of them were grad students, some of them were undergrads, some of them were affiliates, there was really a wide range of different ways that I worked with students and research assistants. We had one weekly meeting, where everybody was expected to attend. So that was a sort of ritual where we’d touch base and I would give goals and guidance to everybody for the week. I also had somewhat of a hierarchical structure, where students who had been there longer would be responsible for training some of the younger students, and by younger I don’t mean age, but the newer ones. A lot of the culture in a research lab isn’t about hiring skilled personnel, it’s about training HQP [Highly Qualified Personnel], that’s what we write in the grant proposals [laughs]. So I hire students with potential who don’t necessarily have the skills that I want them to have, and part of what we do is train them. I would pay them to take workshops or classes, but I would also really expect them to teach one another and I would hire very complementary kinds of personalities who could teach each other, and the work is intrinsically interdisciplinary, which is where I think you’re going with this anyway. So that kind of collaboration was really crucial to the success of the work.

I’m very interested in research-creation. Would you say there’s any divide in your work between the research and the creation? Do you have a space more for inspiration and a separate theoretical component, or is that tied together for you?

It’s really tied together because the creation is about questioning technology and doing things with technology that were not possible in the past. So for me, creation is not about what colour is it — let’s talk about garments since we make a lot of those — it was never really about, what does the garment look like — it is, what would it mean to have a garment that moved on your body and moved in an uncomfortable way? What would it mean to have a garment that needs energy but doesn’t have batteries and needs to harness energy from the environment or from somebody else’s body. So for me that’s the creative aspect, and then being able to formulate that into a research question that leads to a successful research grant proposal. And then, working with a team that is very creative, so that the potential answers to these questions that we suggest can be described as beautiful or evocative or playful. And they do get invited to be shown in galleries and museums, which I guess is sort of the institutional stamp of approval for the creation side. I’m not an artist. I’ve never had a solo show as an artist. I really think of myself much more as a researcher. But a big part of my dissemination happens in museums and galleries.

So you wouldn’t consider yourself an artist, but you show in galleries? And your inspiration is not so much connected to the fashion, but connected to questions about technology?

Yes. Like how can we really break down what a garment is. Or what a textile is. And how can we use all of these emerging materials that are being used in aerospace or the automobile industries or whatever, but use them in garments. What kinds of new functionalities would they enable? New forms of expression. New ways of connecting with one another. But also, how would they help us understand the world in a different way? Question the world. The project Caption Electric and Battery Boy is really about questioning our dependence on energy and batteries and portables. The major point there was to create garments that are sort of ridiculous and uncomfortable. And the thematic that runs through it is one of fear and paranoia and fear of natural disasters and protection, so it’s deeply linked. And then in order for me to be able to raise the money that I’ve raised that’s more from the sciences and Engineering, there’s always a very strong scientific or engineering innovation in the project. And I would feel like a fraud if there weren’t.

Do you think with working on very highly funded projects, with industry and with big labels, do you see that as in any way compromising your vision? Or extending it? Do you find that working with big industries provides a positive constraint or something where you have to really compromise your creative work?

It’s a different kind of vision. I don’t see them as contradictory. The obstacle to work in my experience has just been the really kind of overwhelming bureaucratic aspect of administering large research grants at the university, where I ended up just spending so much of my money doing paper work and filing reports and filing expense reports in a thoroughly inefficient way… Industry can’t afford to have the same kind of level of inefficiency that we have in academia… They would go out of business. So that’s super refreshing. Of course then we have a board of directors that we have to answer to. We have to show a business model that would be profitable with an X amount of years. Whether that business model involves being acquired by Google or having sales or whatever, I mean that’s another questions, it’s the VC [Venture Capital] world.

That’s interesting, because usually we see the academy as the place where we can sort of nurture our bigger ideas and industry as a place where we have to compromise. But that’s not your experience?

It’s different ideas. But what’s really exciting is there’s different kinds of industry. And right now with the start-up culture around new technology, it’s all about innovation and wonder and discovery that, sure, you have to have a business model, but that can be viewed as a benefit rather than an impediment… I’ve also worked on projects with creative studios. So industry doesn’t necessarily mean military or medical devices. Industry can also mean Cirque du Soleil. Or working with PixMob, which is a great company, some of my ex students started it. So industry, sure, has to have a business model, and if it’s not profitable, it will go out of business, but it doesn’t mean you don’t innovate or you don’t do exciting work. And sometimes innovation is actually stifled in academia because of all the bureaucracy and paper work. I’m being provocative of course. Because all of the assumptions you’re bringing to that question are true, but there’s also that other side.

You said you don’t see yourself as an artist. What do you think the differences are between art and design?

Everybody is going to give you a different answer. But my answer these days is that art is about one individual and design is about multiple individuals. And of course people will argue with that and I will change my mind eventually, but that’s how I think about it these days. So for me, design fits a lot better into this research model where we have multiple authors for each project. It’s almost like thinking of the research work as a theatre performance, or a play, or an orchestra, where you have a conductor, but then everybody gets credited for their own role. Whereas I find a lot of the art research-creation, it’s still about the one person who takes credit for everything even though they might have a team of people working with them. But also for me design is perhaps a little bit more concerned with the tools, the materials, the processes, rather than like the final moment of showing the piece.

So in design there’s more of a process?

No, it’s not that there is more process, but the process is almost more important than the final piece, for me, okay. Whereas the way that I think of art is that the final artefact is given more importance, culturally. In design research, the process, the materials, the steps you took, are maybe just as important or even more important. And especially when you look at that whole movement of speculative design. Or critical design coming out of the UK, with people like Dunne & Raby. In fact, there isn’t really a final outcome, but it’s all about these trajectories and interrogations and asking “what if?” and showing these speculative processes. Or experimenting with materials. But not necessarily building up to the one artefact that will go into a permanent collection somewhere.

But say with industry you would need to eventually produce an artefact—

—Yeah, you need a product—

—Or else they would be like, “where’s your product”—

Well not necessarily, because also patents are a very viable outcome of industry work. So I’m writing a lot of patents right now with OmSignal. And those aren’t artefacts. That’s IP [intellectual property] that has a high monetary value.

In your work, for example in your Skorpions dress, you describe the dress as parasitic and the wearer as a host, so a lot of agency is given to the actual items that you create. Do you see what you do as somehow aligned with biotech? These garments are almost coming “alive”?

To me, a lot of interaction design I find problematic around the idea that the human is always in control or needs to always be in control versus the idea of giving up control a little bit. And maybe that’s also just a personal philosophy as well. With being a mother. Raising two kids in this very unusual sort of circumstance where I’m not their biological mother but I’m their full-time mother and yet I don’t have the same kind of control… So I think for me, my personal life experience has also influenced the way that I think about interaction design… It’s less about biotech and more about control.

It sounds a little like actor-network theory. We read this also in communication with Stewart Brand. And the fact that objects or technology can dictate the way things go, not necessarily just the human.

One of my favourite quotes from Sherry Turkle is that computers aren’t just a projective medium, but also a constructive medium [See Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (New York: Simon and Schuster), 1984]. You control or project your desires on them, but they also shape what your desires are.

So it’s a collaboration in a way between the human and the technology? And this is maybe freeing?

Well, the reason I can do these things is that I’m not in an Engineering faculty where each project has to be about solving a specific problem that is then quantifiably successful or unsuccessful. I can produce these projects that exist in this much more qualitative research space, whatever that means. I don’t have to have tables and graphs for each project that I make…. I don’t need to do those kinds of quantitative studies for my research, which allows me to explore these questions that are more — sometimes I say they’re poetic — I don’t have a very rigid theoretical structure for how I talk about these things. But it’s definitely great to have a freedom not to need a quantifiable result at the end of each project.

Is there anything about your lab that you would like to change or that you find problematic? Say, in terms of space?

When we were in that corner space on the 10th floor, that was too small. At one point if you can imagine I had about twelve people working in there with all kinds of sewing machines and electronic stations, so that was nuts. The thing that makes a space successful is to allow everybody to feel ownership over a portion of the space. You need everybody to feel like some small portion of it is their own. To develop a level of trust where people can leave things without worrying about them being either stolen physically or the ideas stolen, so actually working on a culture of collaboration and trust is really important. Definitely in my particular discipline where we need machines there’s always going to be the need to go to other spaces to use different kinds of specialized machines or facilities. But the space itself — it’s more about the culture you create in the space, about exchange, about giving, and the way that I fostered that from the very beginning is by having a lot of parties and 5à7s. It’s all about building trust.

All images taken from the XS Labs catalogue.

The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>On the day of July 23, 1926, a strange case passed before Judge Harry Trelawney Eve. On the surface, it seemed like a pretty straightforward matter of copyright in which one Geraldine Cummins was contesting the rights of one Frederick Bligh Bond to a work called The Chronicle of Cleophas. The thing is: Geraldine Cummins was not claiming that she had authored the work instead of Bond; she was saying she was the medium through which the work had been channelled.

The Chronicle of Cleophas, asserted Cummins, had been received incommunicado with the spirit world through the interface of a Ouija board, over a period of about a year or so, and usually in response to questions she had been hired to answer by clients as a paid medium. As for the defendant, Frederick Bligh Bond was employed by Cummins as an assistant and had acted as amanuensis to the various Ouija board messages being received by the medium; in the words of Jeffrey Kahan, “for each of Cummins’s Spiritual communiqués, he [Bond] ‘transcribed it, punctuated it, and arranged it in paragraphs, and returned a copy of it so arranged to the plaintiff [Cummins].’ He further stated, and Cummins did not contradict his statement, that he, Bond, ‘annotated the script, and added historical and explanatory notes’” (92). If you’re confused at this point, you’re not the only one.

We have here a literary shell game, in which authorship is shuffled about until the client is utterly baffled. The difference is that, in a shell game, the client (or “mark”) understands who is doing the shuffling. In the case of a séance no one seems to be the creative center . . . The multiple hands recording the Spirits creates the impression that the creative center is not physically present (Kahan 91).

Who, then, did Judge Eve decide in favour of in 1926 — the medium who channelled the work, or the scribe who wrote it down, arranged, and edited it? And why should we care?

“Walk through a museum. Look around a city. Almost all the artifacts that we value as a society were made by or at the order of men. But behind every one is an invisible infrastructure of labor — primarily caregiving, in its various aspects — that is mostly performed by women.” In her 2015 article “Why I Am Not a Maker,” Debbie Chachra challenges a cultural attitude that privileges the act of making over the more invisible acts behind it, particularly the gendered acts of caregiving and educating. Walk through a text. Look around at the letters and words and margins and paper. It was the mediums of mid-19th-century Spiritualism — an almost across-the-board female labour force — who presented a challenge to one very highly traditional order of men, namely, the order of the author.

What finally materialized in a court of law in 1926 was a practice that had in fact been a booming industry since the Fox sisters started charging admission to rappings on tables in 1848 and mediums started channelling under the moniker of Spiritualist and publishing under the monikers of spirits, which was, according to Bette London, “for some the only way to put themselves forward as authors” (152). This is a practice that literalizes Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar’s statement that “[a] wealth of invisible skills underpin material inscription” (245). The case of Cummins v. Bond is not so much a case that brings to the fore the act of making, nor does it propose a refusal to be a “maker” as Chachra puts it, but rather the act of unmaking.

For the purpose of this probe these themes will remain a little superficial, but the surface is the best place to start here. The title The Chronicle of Cleophas, throughout discussions of Cummins v. Bond, remains just that, a title without a content — the book is rarely considered in its own right and finding a copy of it leads to a ghost town of an Amazon.ca page where The Scripts of Cleophas is (hauntedly) housed. This is exemplary of research into automatic writing, the products of which are sometimes so illegible they cannot even be read, as in the invented language of medium Hélène Smith, who called her script “Martian.” Automatic writing, also called psychography or spirit writing, offers a process of writing in lieu of a product (the continuous verb writing rather than its gerund), and furthermore a process of writing in which the produced work is secondary if not tertiary to the act of creating it; a “transitional object” that connects the “sensory body knowledge of a learner to more abstract understandings” (Ratto 254, emphasis his own).

In his 2011 paper, Matt Ratto outlines his experiments in “critical making,” which address a “disconnect between conceptual understandings of technological objects and our material experiences with them” (253). I was struck by how closely the drawbot, which Ratto had his participants construct in one of his workshops, resembles the planchette that automatic writers used during séances in the 19th century. Whereas the drawbot moves across the paper by a process of mechanization via a small motor, the planchette moves across the Ouija board or piece of paper by a process of automaticity via the participant’s hand, part of what the Spiritualists called channelling, or what a cognitive scientist may call ideomotor action. My main question here is, how could the Spiritualist practice of automatic writing be revived and refigured as a model of critical making — where critical making combines critical thinking, a less goal-oriented form of “making,” and conceptual exploration (Ratto 253)? What would this look like and what are the “wicked problems” it could address?

In my last probe, I explored how sleep could be an interesting object of exploration for a Media Lab; automatic writing by contrast offers a methodology rather than an object — not so much the axis around which questions can be posed, but a way to create the questions in the first place. As sleep unmakes waking and any easy notions around consciousness, automatic writing unmakes the author-function and any easy notions about what it is to write.

The real difficulty is who or what is “Cleophas.” If it be assumed (which nobody can prove) that “Cleophas” has a personal identity of his own and could have been the author of the writing, his evidence would be material. “Cleophas” might be sworn and cross-examined by the process of automatic writing. Instead of being difficult, this might be no trouble at all. Once “Cleophas” is accepted as a real person, the problem of communication involved in swearing him and examining and cross-examining him very likely would not be as difficult . . . (Blewett 24).

Who or what is “Cleophas”? What is automatic writing? How does it work? Is it a shell game, as Kahan suggests? An experiment? A literary device? The fact that the above quote comes not from literary criticism, but The Virginia Law Review, 1926 edition, is indicative of the ripples Cummins v. Bond was causing in terms of conceptions around authorship, marked not least by the quotation marks unrelentingly hovered around the Cleophas in question. “Cleophas,” we could say, is an assemblage, as is, we could also say, any “writer,” as is any piece of “writing.” In “What Is an Author,” Foucault discusses how the 19th century saw the rise of a figure who was not just an author of a text, but an entire discourse, such as “Freud”; “Marx” (228); at the same time, the practice of mediumship that cropped up with automatic writing composed the other side of the spectrum of this canon, folded it back, threw a mirror up to it, but one that hardly anyone was able to see. In the case of Cummins v. Bond, it was the medium Geraldine Cummins who came out victorious, and not Frederick Bligh Bond who’d physically held the pen to record the text. But what is not recognized in either the resolution of this case or the Amazon.ca screenshot above is that on the title page of The Scripts of Cleophas, Geraldine Cummins credits herself as “recorder,” not as “author.” Though she won the case, she was still not granted the right to self-representation. According to Jeffrey Sconce,

Long before our contemporary fascination with the beautific possibilities of cyberspace, feminine mediums led the Spiritualist movement as wholly realized cybernetic beings—electromagnetic devices bridging flesh and spirit, body and machine, material reality and electronic space (27).

It’s a seductive notion, but, really? The mediums of 19th-century Spiritualism often published under the male names of the spirits they were channelling and thus, as London pointed out above, were able to publish at all, and furthermore earn a living for themselves in a position of power as mediums. The history of automatic writing, in contrast to Kahan’s statement, is physically present. These days, our automatic writers are quite literally transitional objects, drawbots: in 2014 alone, one billion stories were generated by Automated Insights’ Wordsmith program (Podolny), which uses NLG algorithms to “write” articles, while tamed automata are often gendered female, such as Siri, Archillect, “Her.” The embodiment of work and working is changing, and so are the questions surrounding it. How could a writing process that is seen as plural from the get-go change discussions around copyright? What does automatic writing say about fanfic, for example, or creativity, labour, or the ways in which these categories are parsed out according to gender? Finally, if the question, as Bernhard Siegert proposes, is no longer “how did we become posthuman? But, how was the human always already historically mixed with the non-human?” (53), then maybe we can also ask: is there any writing, has there ever been, that is not automatic?

Works cited

Blewett, Lee. “Copyright of Automatic Writing.” Virginia Law Review 13.1 (November 1926): 22–26.

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic, January 23, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” [1969]. Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault. Ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977: 113–38.

Kahan, Jeffrey. Shakespearitualism: Shakespeare and the Occult, 1850–1950. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979.

London, Bette. Writing Double: Women’s Literary Partnerships. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Podolny, Shelley. “If an Algorithm Wrote This, How Would You Even Know?” The New York Times, March 7, 2015.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27 (2011): 252–260.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.6 (November 2013): 48–65.

The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>The post We are All ‘Super Slick Salesmen’: A life as a living historian in the retro-utopia, or, I have an amazing post-apocalyptic bug out team – probe on the MIT Media Lab appeared first on &.

]]>Most of the world today runs on ‘fixed-term contracts’ (Barbrook, 1995, p. 2). Long gone is the notion of staying in one job or company for an entire career. When I began my career as a historian, Mulroney had decimated the history staff at Parks Canada, and many of the community museums in Nova Scotia were only seasonal. I knew early on that I needed to diversify my skills and always be ‘on the lookout’ for the next contract. There was no “guarantee of continued employment” (Barbrook, 1995, p. 2), there wasn’t even a guarantee of summer employment! All that aside, for the most part, Nova Scotians have put their ‘big girl panites’ on and figured out how to live a meaningful life. Like Europe, we understand the need “for an enlightened mixed economy” (Barbrook, 1995, p.8). There is no job that is deemed ‘too menial’, in fact many of the people behind the counter at Tim Horton’s have degrees of higher learning, some of them multiple. The running joke in my family has long been ‘Dr. Grant to the centre cutting table’ because to return to Nova Scotia may mean a return to working at Fabricville.

So what’s a historian to do?

In Robert Hassan’s article “The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life” he asks “what are some of the possible social, cultural and ontological consequences of ‘being digital’ within a hypermediated digital ecology of interconnectedness” (Hassan, 2003, p. 89)? Hassan tells us that the MIT Media Lab looks at ‘Sociable Media’ and how people percieve each other in a networked world, and the ‘Digital Life’ looks at connections between ‘bits, people and things in an online world’ (Hassan, 2003, p. 90). As I have mentioned in class before, part of my life is spent online interacting in online history communities. This is not really all that different from most people’s lives. Everyone has online communities that they frequent. What is a bit different for me, is that the online world is also my work world. “[T]he ‘real-time’of the online environment [has] become the ‘real-time’ of [my] everyday life” (Hassan, 2003, p. 90). My peer-group has come to realize that we can use technology to create a space for working, sharing research, and networking with historians and museum sites all over the world. We have found a space that is between the ‘good and evil’ of technology, in that we all use it, begrudgeonly for some, but that it can be a useful tool for us to develop the networks we need in order to remain in the history field (Hassan, 2003, p. 91). For many of us, dabbling in webpage development was just too cumbersome a thing to maintain. Facebook though, proved to be an easy interface to use. Add to this many blogging forums that we could publish in and hotlink to facebook, a network could be formed. In a similar fashion to LaTour’s laboratory of a couple of weeks ago, we are able to read other’s research findings, share and collaborate on new articles, and be in a creative space together, even though we may physically be thousands of miles apart. A cocktail party in our network would have to be done over skype, with each of us sitting in our own home offices, probably over coffee instead of alcoholic drinks. “Media has become critical in popularizing me as a person in the historical community” (Hassan, 2003, p. 92).

So my work life and personal life have become blurred into one. My online prescence is strictly developed to provide ‘good press’ (cited in Hassan, 2003, p.93). I am constantly reading about the eighteenth-century and its fashion, I am hoping to soon fully contribute to that discussion instead of just the occasional comment. My own trips to the past in the form of re-enactment are not only sales trips in that I am still making clothing for interpreters, but also research and networking trips as I learn of new pieces of extant clothing that I will want to study for the disertation. In both instances, I have to be ‘on my game’. Unfortunately though, despite my offering a ‘commercially viable product’ (Hassan, 2003, p. 93), I am not being paid unless I have provided an article of clothing as part of the exchange. I am still being paid for what I do, not for what I know, and that tends to relate to a lower dollar amount. Hassan tells us that “ICTs have flooded the lives of many within the advanced economies, that it is increasingly possible to speak of life being conducted within an information environment, an informational ecology” (cited in Hassan, 2003, p.95). How to earn a living from this ‘interconnectiveness’ will be the question on many historians lips before too much longer.

I will admit that I am extremely privledged to be who I am in this world, an historian who is not employed in the traditional sense, a graduate student. If it were not for my husband’s steady job, neither of these parts of my life would happen. I would be that struggling, retail sales associate at Fabricville, cutting your fabric, asking you what you are making, and if you need thread (questions we all have to ask, not that we are interested). I would not be sitting here at the computer thinking philosophical thoughts about ‘interconnectiveness’, I’d be worried about paying rent and buying groceries. These two things are still in the back of my mind though, because I have been that retail sales associate. And so this past week, along side my philosophical ramblings, I have been carrying out a time honoured tradion of processing the Fall harvest for consumption during the winter months. Alongside my friends in other parts of New England and the Maritimes, I have been making pickled veg, filling my freezer with other freezable vegetables and meats. If you live in an area where there are farms and farmers, food tends to be cheaper right now than any other time of the year. Also, since I have just received my term disbursement cheque, I have money. Money that was almost entirely spent on food for the winter months. Other friends of mine are processing their flock of chickens and turkeys, others still have gardens full that need to be ‘put up’ for the winter. Next summer, I too will have a garden full of things that we can eat. This summer was a write-off, as we did not move here until mid August, instead of the first of June as we had originally intended. I have other friends who are now finishing up their summer employment and are getting geared up to begin Winter projects for themselves, or to suplement their income producing items for museums trying to use up budgetary money before the end of March.

By now, you will have noticed that I haven’t cited the Brand reading. Having tried to obtain a copy of the book to read, I learned that it is not available as an ebook (technology), nor, despite there being several copies available, is it available for shipping until after christmas, unless I sign up for a costly Amazon shipping package that I will never use. In the meantime, I have been reading about the MIT media lab through other sources. I have been thinking about technology and how it was supposed to make our lives so much easier. One would think that by now, most books of this sort would be available as ebooks. My mum devours fiction now only as ebooks or audio books, which saves our bookshelves for books on art and topics that we are constantly researching. And then I think about what would happen without technology (there was a recent fiction novel about a post technology state and how re-enactors were able to build a new society, it was the SCA, but the skills are similar). I still wouldn’t be able to read an ebook entitled The Media Lab:Inventing the Future at MIT. I have been thinking about the community I have become a part of through the internet. How I would miss those friendships that I have developed. Hassan informs us that the time-space compression that technology provides was part of the acceleration of modernity, centrally connected to capitalist development. He explains that tech has changed the lives of many people in profound ways on a macro level (Hassan, 2003, p. 102). But what of the micro level? My own life would change without technology, certainly. I would have to think harder about the micro of daily life. How important a good cooking fire is; that hot water is a chore and a blessing when it doesn’t come from the tap. But then I think of the things that I know how to do, the knowledge that has been passed down to me from my parents and grandparents, the knowledge shared amoungst my peers. Daily life would be harder, but livable.

Especially if we up and moved again, to be closer to our friends, our post-apocalyptic bug out team.

Works Cited

Hassan, R. (2003). The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life. Media, Culture and Society, 87-106.

Richard Barbrook, A. C. (1995). The Californian Ideology. Mute, 1-8.

Works Not Cited

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. Chapters 1, 6, 9, 13.

Post Script

Last week I wrote a whole other probe about tech and how I live my life with tech, but still do a lot of non-traditional, low tech things at this time of year. That my life is a balance of tech vs. non-tech, leaning towards the non-tech. I was missing the last readings, from the Brand book though, and even commented on how my inability to find those readings ticked me off. This is why…

Thursday, before class, I went in to the Library and found a hard copy of the book. Yes, I could have done this right from the beginning, but I was told ‘just go on to google docs and look for the readings’. Having done that, I really could not find the readings. Further searches informed me that there was ‘no electronic format’ of this book, but that I could buy it from Amazon for the low-low price of one cent. I thought, ok, for one cent, that, even with shipping costs wouldn’t blow my budget. I could do this. I wanted a hard copy, printed out anyway, so that I could make my comments in the margins and highlight the hell out of it. You really can’t do that with a library book, the librarians kinda frown on it. The problem was, with regular shipping, the book wouldn’t get to me until February, unless I bought into Amazon’s expensive ‘free’ shipping program, Prime. I could get six months free trial and then cancel without being charged. Well two of my friends have fallen for this trick and have been charged, and have had a difficult time getting out of the contract, so I was hesitant…and so, I went to the library.

The thing is though, this book is about tech that was being developed 30 years ago. Think about that. Thirty years ago, I had no idea what the internet was. No idea what email, or list serves, or even really what a computer could do. Thirty years ago, I had just written my first computer program, in school, one that made a turtle slowly walk across a bar of music that made the notes play as he passed over them (paintbrush) (Brand, 1987, p.96). This was four years before I would know about something called the intranet, four years before my family would own ANY kind of modern tech. Hell, we had only just gotten a microwave!

As I have told you before, I spend a good part of my day on the internet, on social media, on J-stor, on youtube. A lot of my social life is there, as my friends are far flung, not only in Nova Scotia, but in the US, out west, in the UK, Germany. It is our own version of the ‘vivarium’ (Brand, 1987, p.97). It makes me feel a little less alone. I think J-stor is one of the very best inventions ever, and I am so happy that I will still have access to it, long after I leave Concordia.

Youtube has become my television. I have separated this one out because I think it’s as important as the fact that I couldn’t get the Brand book in electronic format. Brand talks a lot about tech in the book, tech that has been developed in my lifetime. Things that have caused me to have an easier life. It started with the VCR, because at about that same time, my migraines started to get really bad, and I began noticing that I couldn’t watch movies in the theatre any longer without coming away violently ill. We had a small screen TV at home, and my dad would rent a VCR on the weekends and a bunch of movies and we would have a great time, all curled up in my mum’s room until long into the evening. We watched all the classics, concluding each weekend with another great Cheech and Chong movie. Yes, my parents were/are weird, and I love them for it. We had a great video store at home, whose staff were into some ‘other than normal Hollywood’ stuff. I became a great fan of stuff produced in the UK and Europe. The plots were often better developed, and the scenography ‘quieter’ on the eyes. Now, I watch a lot of those films on Youtube. The problem with Youtube isn’t the interface really. That is really easy to use, and the search engine’s great, and the fact that it’s algorithm remembers me is really not creepy to me, and has been helpful in finding things for me to watch that I wouldn’t know to search for, like Timeteam. The problem is that I have to wait for other people to upload the programs I would like to watch to Youtube. I, living in Canada, do not have access to the programming of the BBC. It is ‘blacked out’ here. We have BBC Canada, but often it is just a rehashing of programs produced here in Canada, like Holmes’ and Baumler’s renovation programs. Not the BBC at all.

Timeteam is a UK based show where a team of archaeologists have two days to go into a site and do an archaeological survey. The stuff they find is fascinating. If the site is rich, then there may be follow-up digs on the site at a later date. All the seasons are there, on youtube for us to watch. I have gotten many of my friends hooked on the series. Youtube is also where I ‘met’ Ruth Goodman, and her team of living historians doing a job that I could only dream about, actually living history for a period of time, in a historical place. Living history allows me to have a better understanding of how historical clothing works. In some of the historic sites that I have worked, we have been able to do experiments on clothing, noting wear patterns, how clothing is changed by the wearing, and how the body is changed by the clothing worn. It then helps me to understand what I am looking at when examining an extant garment. I can understand if it has been altered, and often when, and for what purpose. I have also come to the understanding that a lot of the myths being spread about clothing in our grandparent’s time and before are truly that, myths.

But let me get back to Youtube, and technology…

The UK is big into Living History. I capitalize it on purpose, to try and explain how big it is in the UK. Their museum system is almost entirely federally funded. And they are swimming in historic sites. It is so important that the BBC has an entire channel devoted to historical stuff, and I’m not talking about Ice Road Truckers or ‘Alien’ anything here, actual HISTORY! And so these shows are being produced, and people watch them, and they grow to like their own history. Here in Canada, we get stuff from the US, which by and large is dramatically plotless, and uses far too much special effects and flashy filming techniques to make the viewer think they are getting something new and fabulous.

I have been home sick this week. I have been watching (listening to, really) a lot of home improvement shows. I am bored, but cannot stay awake long enough to continue with my readings. It is really hard to concentrate on stuff you want to write about when you lose your place on the page twelve times before the end of it. I can watch a home improvement show and it really doesn’t matter who the host is, I can see the problems coming a mile away with the shallow plot techniques and know how the show will end, in case of napping. Sitting at my computer to watch Youtube is problematic when sick, it is cold outside of bed, and uncomfortable sitting in my desk chair all day. And yes, in case you haven’t realized it yet, my bedroom TV is still a dumb TV, and Pierre detests it when you set a laptop on the bed…he is a techie.

I have brought you on this quick rant because by now, thirty years after the Brand book was written, I figured that I would just be able to watch anything I wanted to watch (produced anywhere in the world), when I wanted to watch it, on just about any surface in my home. Or maybe not on a surface at all, that TV would be like Princess Leia’s hologram from Star Wars. That I would be able to explore the space all around the ‘program’, looking to see what I wanted to see, from the comfort of my own home, from bed when I am sick. Thirty years in though, I am still stuck watching a lot of bad TV from the United States, which now, Pierre tapes and we watch when I can handle the flashing for a period of time…which lately has been growing shorter and shorter, along with the list of programs I can handle both the flashy filming, and the seriously bad plotlines. I seek a better quality of life, one where my day can consist of watching the programs that inspire me, while I work on my studio work, and converse with my friends and peers on the latest research. All in real time.

Works Cited

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. Chapters 1, 6, 9, 13.

The post We are All ‘Super Slick Salesmen’: A life as a living historian in the retro-utopia, or, I have an amazing post-apocalyptic bug out team – probe on the MIT Media Lab appeared first on &.

]]>The post Becoming Posthuman: Disappearing Bodies & Dance as Thing-Power appeared first on &.

]]>For the last few weeks we’ve been talking about assemblage, objects, infrastructures and articulations. But we’ve also been talking about bodies. It seems impossible to escape perceiving, feeling and thinking about the world from our subjective, human position, even when we employ object oriented ontology to level the playing field between humans and things, as we did this week. But is it possible to eschew correlationism or think a world of things outside of our human subjectivity? Our readings this week (specifically Latour and Bennett) prompt a conception of the human (body) that is no more privileged than the “things” that shape and surround it.

Some questions:

Where do the lines between human/nonhuman entities and bodies/technologies exist?

Are those lines always already blurred?

Can (nonhuman) objects have agency?

What is agency anyways?

For Bruno Latour, the agency that the “nonhuman delegate” possesses is its ability to impose behaviours “back onto the human” in a method that he (and Madeleine Akrich) call “prescription” (301). In Latour’s famous example of the mechanical door-closer, behaviours such as walking quickly when passing through the doorway and holding the door for others before it slams in their face are “prescribed” to humans by the non-human apparatus of a spring-loaded mechanism. Similarly, Latour explains, one can learn better how to drive a car by actually doing the driving than by just reading a manual. “Prescription” is an “embodied,” “intra-somatic” practice (305). Jane Bennett’s work sits somewhere on the spectrum between ecocriticism and speculative materialism, and therefore a large part of her project has to do with rethinking the body of the human subject, not as transcendent, natural or given, but as an assemblage of nonhuman materials.

Latour writes that he “sees only actors—some human, some nonhuman, some skilled, some unskilled—that exchange their properties” (303). Likewise, Bennett wishes to “flatten the ontology” between human and nonhuman entities. She prefers the term “actant” to “actor,” as “an actant can be either human or nonhuman: it is that which does something, has sufficient coherence to perform actions, produce effects and alter situations” (355).

Latour briefly touches on the computer as an actor in his paper, joking that he “talks” to his, making it (the computer) more like a human, but he fails to say how he has become more like a computer. Of course, this type of analysis (of how our technologies are making us less human and more programmed/robotic; how texting is ruining our ability to converse, etc.) is by now old news. In her influential work How We Became Posthuman, Katherine Hayles writes that our daily interactions with various screens and cybernetic systems do indeed change us: “As you gaze at the flickering signifiers scrolling down the computer screens…you have already become posthuman” (xiv). By putting Latour and Bennett in conversation with Hayles, we can think about how information age technologies produce new definitions of (human and nonhuman) agency and behavior, including a disintegration of the body as we know it.

Consider Freya Olafson’s 2013 performance artwork HYPER_:

In HYPER_, technologic objects and practices intertwine with Olafson’s corporeal feminine presence, granting her an (albeit temporary; albeit visual) “erasure of embodiment” (Hayles 4) and “independence from subjectivity” as rooted in the materiality of her body (Bennett). Bennett describes “thing-power” as “the nonhumanity that flows around but also through humans […] a protean flow of matter-energy” (349) that can be detected in actants like electricity, oil and methane (Vibrant Matter).

I would like to propose that the kinds of artistic techniques and kinetic affects produced in HYPER_ stand as a visualization of Bennet’s “thing-power,” a manifestation of the swirling movement of the materiality and information at the “heart of the condition of virtuality” (Hayles 14).

As the show begins, the lights come up on Olafson wearing a black strapless dress that fragments her body by highlighting her chest, arms and face and erasing her torso into the black scrim behind her.

Olafson assumes dancerly poses, at once both sexualized and mechanical, stopping now and again to check for her pulse. Even she, it seems, is unsure of whether she is human. Over the course of the piece, Olafson inhabits various states of “undress” by donning a bodysuit printed with human musculature and then, later, a skeleton painted directly on her skin.

HYPER_ features a mix of dance, computer animation and improvisations with technology to strip Olafson’s human body down to the “assemblage” of skeletal and muscular structures of which it is composed. If humans are, as Bennett posits, made up of a “particularly rich and complex collection of materiality,” then her further statement, that “agency is a property less of individual entities than of assemblages of humans and nonhumans,” prompts us to ask questions like where does agency really lie? (359, 360). Indeed, it is sometimes unclear who or what is controlling or motivating the dancer’s disintegration in HYPER_. Olafson’s blank eyes and listless movements suggest a lack of agency, yet these moments are interspersed with bursts of incisive kinetic energy that indicate intentional action.

In a section of her piece called “Release Technique” (7:56), Olafson projects a video of a movement study game, featuring an animated woman whose body the player manipulates through keystrokes in order to facilitate her free-fall, maneuvering her around and between large round obstacles that block her path.

The female body in this “virtual choreography” is disturbingly corpselike (her eyes are closed, her limbs are limp) and dressed in overtly-sexual attire (a black string bikini). Also unnerving is the violence the player must perform upon the female body in order to guide her path: bending her in half, hyperextending her joints and allowing her to fall directly upon her face. In fact, the virtual woman’s inhuman flexibility is the only feature that saves her body from being completely cumbersome to the game’s goal — ultimate maneuverability. That the game has no endpoint suggests an infinite infliction of brutality upon this virtual body, and the effect is both mesmerizing and revolting. What effect, I wonder, does this technological sadism have on real bodies? Is the virtual (or simulated) body more human or more nonhuman?

Towards the end of the piece (42:40), Olafson emerges from the wings having painted her limbs, torso and face with glow-in-the-dark paint to resemble a skeleton. When viewed in darkness, and with the 3D glasses provided, the rest of Olafson’s human body melts away and the audience is left with only her performative skeletal presence, which, aided by a projection, has now multiplied by three.

When she dances with her skeleton clones, they are a balletic trio that dance in perfect unison, a feat technically impossible for three real human bodies. Her counterparts are both completely her yet also separate from her, a fact that fuses the mechanical and the corporeal into a kind of emotionless ecstatic sublimity, enacting what Hayles calls our “ultimate horror” — the nightmare that the machine might absorb the human being, trapping them within “inflexible walls that rob them of their autonomy” (Hayles 105). By this point in the piece, Olafson has transformed from perceptibly human to something “other” — a cyborg presence at once both material and ephemeral, “cold” and “warm.” She dances her way through this transition, her body always in motion.

It is interesting that Olafson should use dance as her metamorphic medium. Scott R. Hutson calls the specific type of movement inspired by electronic dance music and the rave scene “dance as flow” and he notes that this type of dance “merges the act with the awareness of the act, producing self-forgetfulness, a loss of self-consciousness, transcendence of individuality and fusion with the world” (Hutson 39). The self no longer controls the body. Instead, the movement of the body becomes involuntary, controlled by music and rhythm alone, allowing the mind to abandon it. Because HYPER_ performs an illusion by which the body is dissolved into pure movement, it works as an example of the shift that Bennett also makes, from body materialism to thing-power materialism. Whereas body materialism “has tended to focus on the human body and its collective practices” as well as “the extent to which cultural notions and ideals are themselves embodied entities,” thing-power materialism “focuses on energetic forces that course through humans and cultures without being exhausted by them” (Bennett 367).

HYPER_ ends with a visual of swirling red and blue ribbons, like rogue DNA strands. The ribbons, which are guided by Olafson’s unseen hands, move in abstract and haphazard (“aleatory”) ways; they are the unpredictable flow of information, materialized. Although they are manipulated by a human’s (invisible) hands, the resulting movement of the ribbons can be seen as an artistic representation of Jane Bennett’s thing-power materialism or “vibrant matter,” possessing as they do, an “active, earthy, not-quite-human capaciousness” (3).

Tensions of autonomy and control, intimacy and impersonality plague HYPER_, which reinstates the body, and particularly the female body, as both a vehicle for and an obstacle to freedom. But what kind of “freedom” is this? What kinds of issues arise when technological escapism is posited as a means of transcendence from the body? Is the result a kind of neoliberal fantasy? Computer technologies have claimed that they can help us accomplish all that neoliberalism requires of us — precarity, availability, un-rootedness, distributed agency and skill. Is the body just a hindrance to these qualities?

Works Cited

Bennett, Jane. “The Force of Things: Steps Toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32.3 (June 2004): 347-372.

———-. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. London: Duke University Press, 2010.

Hayles, Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Hutson, Scott R. “The Rave: Spiritual Healing in Modern Western Subcultures.” Anthropological Quarterly 7.1 (2000): 35-49.Academic Search Premier.

Johnson, Jim [Bruno Latour]. “Mixing Humans and Nonhumans Together: The Sociology of a Door-Closer.” Social Problems 35 (1988): 298-310.

Olafson, Freya, chor. HYPER_. Freya Björg Olafson, 2013. Vimeo. 17 Apr. 2014.

The post Becoming Posthuman: Disappearing Bodies & Dance as Thing-Power appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Squirrel Is Stuck Between An Ocean And A Hard Place appeared first on &.

]]>Approaches to AI in virtual systems and Minecraft

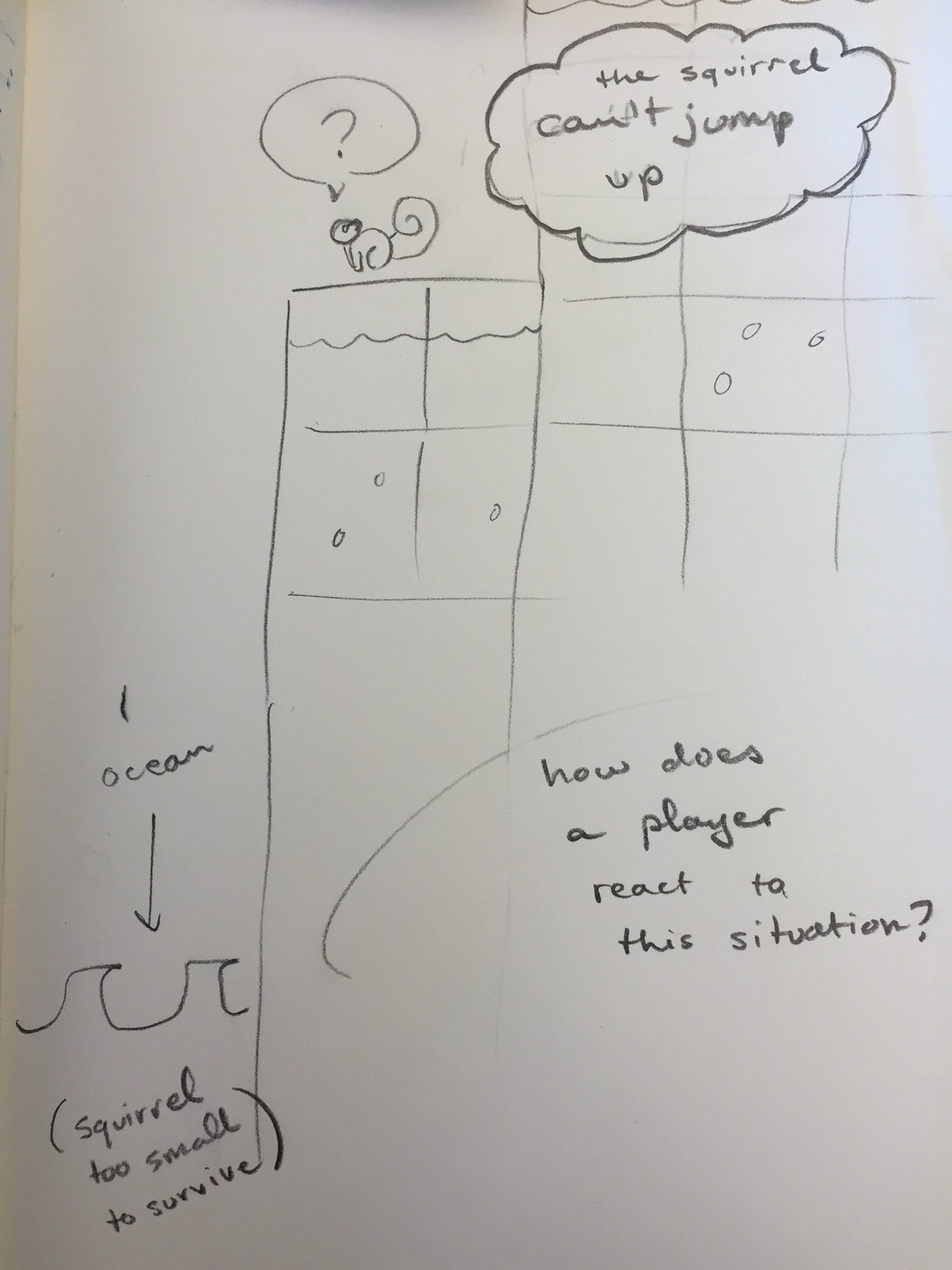

Yesterday, while wandering around the mLab and procrastinating between deciding to go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up and work on midterms, I came across something I have seen many times in my Minecraft play. A small non-agressive mob was stuck between the ocean and a ledge on a cliff, with no means of escape. By small, I mean a mob that is smaller than half of a game “block” (Minecraft’s “standard” unity of measurement) and in this particular case the mob was a squirrel, a colourful addition to Minecraft’s bestiary from one of the mLab’s 130 odd mods. Either it spawned on the ledge or had fallen there, and because of its small size, it was stuck on the ledge, doomed to fall into the ocean if it tried to escape.

Thus the squirrel simply sat there.

In meatspace, or the real world, the squirrel would die of starvation if the squirrel had found itself on that ledge. Perhaps the meatspace squirrel would be motivated by some instinct to attempt to climb the impossibly steep dirt and rock cliff facade.

But in Minecraft, the squirrel is doomed to its fate until the system despawns the chunk of server land that this drama is unfolding upon. The squirrel is doomed to sit there on that ledge, ostensibly for as long as the server chunk is loaded, for the rest of time.

Because I wasn’t thinking of taking screenshots of the stranded Minecraft squirrel last night (sleep deprivation, tsk tsk) I decided to illustrate the situation for you with a sketch:

The squirrel is in a tough situation. As I was fluttering about the server, and I saw this squirrel, my immediate impulse was to dig a little path into the cliff’s rocky face, so that the squirrel could escape to the woods above and go about its squirrelly business.

Why would I do that? Why so much empathy for a Minecraft squirrel?

The squirrel, after all, is just an artefact of computer code meant to do things that I, as a human playing Minecraft, can interpret as squirrel activity. This, and its aesthetic, cue my brain into seeing a “squirrel” as the manifestation of a bit of computer code. Without my interpretation and visual interaction with the squirrel, is that bit of computer code really a squirrel, or just a bit of computer code? If no one is around to interpret the squirrel’s immobile waiting on that rock ledge as panic and despair, is the squirrel really in any danger?

From the perspective of the strip of code governing the squirrel’s activity, that squirrel’s activity makes perfect sense. The computer code has judged the situation and asserted: “There is danger in every direction, but right here is safe. So the squirrel object won’t move. Success!”

It is my interpretation that the squirrel is stuck, and because I think a squirrel should be frolicking about in the woods, I have this idea that the squirrel’s activity sitting on a ledge is somehow unsatisfactory. I am moved to change the circumstances and give the squirrel an opportunity to rectify its activity.

In an interview between filmmaker Gina Harazsti and Dr Darren Wershler (I was lucky enough to see a preview of the footage last week) professor Wershler asserts that the reason we care so much about “cute mobs” in Minecraft is because of nostalgia. We don’t care about skeletons or creepers stuck on ledges with nowhere to go. We are nostalgic about squirrels in Minecraft because we are nostalgic about real squirrels. Is it that we want to play out a fantasy as a human emissary to an animal society in danger? There’s a lot of writing on “cuteness” and its evolutionary function. Are we playing out real-world biases via nonhuman mobs in Minecraft – because the squirrel has a fluffy tail and is so small, are we confusing two very different nonhuman “creatures” – one of flesh and fur, the other an artefact of software.

SO CUTE AND FLUFFFEEEEEEEEEE

When artificial intelligence research and cognitive science were both in their infancy, a piecemeal approach was developed by some researchers who were hoping investigations of artificial intelligence would be a useful tool to reproduce “human” intelligence. In his report Intelligence without representation by Rodney A. Brooks, where Brooks describes research done at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the paper asserts flat out: “Artificial intelligence started as a field whose goal was to replicate human level intelligence in a machine.” This original goal was gargantuan – but there was hope that in isolating the different “pieces” or components of cognition, we could replicate them with mechanical processes whose “brains” would be software. Brooks’ report was published in 1987 and as such presents a particular picture in time for artificial intelligence research – however I have found it interesting to compare some of the points he makes on the breakdown of artificial intelligence into units performing various functions, to the nonhumans of Minecraft.

I examined the points Brooks makes about artificial intelligence research concerned with making robots in the real world, rather than making software interacting in a virtual space. He mentions game spaces with the famous “blocks world” example :

In the late sixties and early seventies the blocks world became a popular domain for AI research. It had a uniform and simple semantics. The key to success was to represent the state of the world completely and explicitly. Search techniques could then be used for planning within this well-understood world. Learning could also be done within the blocks world; there were only a few simple concepts worth learning and they could be captured by enumerating the set of subexpressions which must be contained in any formal description of a world including an instance of the concept.

Brooks however criticizes the heuristic problem solving methodologies used in the “blocks world”, stating they are too simple for serious, epistemological artificial intelligence research. It is perhaps difficult to conceptualize what the “blocks world” was, as it was for me when I first started investigating it, and I stumbled upon SHRDLU – an early natural language understanding computer program. It is basically a programming software that learns to make “blocks” of concepts containing subexpressions. For instance, in a “blocks world” software, you could teach the software that chicken is a type of meat, and that meat is a concept “block” worth remembering for further interactions. An example from SHRDLU illustrates this:

Person: PICK UP A BIG RED BLOCK.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: GRASP THE PYRAMID.

Computer: I DON'T UNDERSTAND WHICH PYRAMID YOU MEAN.

Person: FIND A BLOCK WHICH IS TALLER THAN THE ONE YOU ARE HOLDING AND PUT IT INTO THE BOX.

Computer: BY "IT", I ASSUME YOU MEAN THE BLOCK WHICH IS TALLER THAN THE ONE I AM HOLDING.

Computer: OK. (does it)Person: WHAT DOES THE BOX CONTAIN?

Computer: THE BLUE PYRAMID AND THE BLUE BLOCK.

Person: WHAT IS THE PYRAMID SUPPORTED BY?

Computer: THE BOX.

Person: HOW MANY BLOCKS ARE NOT IN THE BOX?

Computer: FOUR OF THEM.

Person: IS AT LEAST ONE OF THEM NARROWER THAN THE ONE WHICH I TOLD YOU TO PICK UP?

Computer: YES, THE RED CUBE.

Person: IS IT SUPPORTED?

Computer: YES, BY THE TABLE.

Person: CAN THE TABLE PICK UP BLOCKS?

Computer: NO.

Person: CAN A PYRAMID BE SUPPORTED BY A BLOCK?

Computer: YES.

Person: CAN A PYRAMID SUPPORT A PYRAMID?

Computer: I DON'T KNOW.

Person: STACK UP TWO PYRAMIDS.

Computer: I CAN'T.

Person: WILL YOU PLEASE STACK UP BOTH OF THE RED BLOCKS AND EITHER A GREEN CUBE OR A PYRAMID?

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: WHICH CUBE IS SITTING ON THE TABLE?

Computer: THE LARGE GREEN ONE WHICH SUPPORTS THE RED PYRAMID.

Person: IS THERE A LARGE BLOCK BEHIND A PYRAMID?

Computer: YES, THREE OF THEM: A LARGE RED ONE, A LARGE GREEN CUBE, AND THE BLUE ONE.

Person: PUT A SMALL ONE ONTO THE GREEN CUBE WHICH SUPPORTS A PYRAMID.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: PUT THE LITTLEST PYRAMID ON TOP OF IT.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: DOES THE SHORTEST THING THE TALLEST PYRAMID'S SUPPORT SUPPORTS SUPPORT ANYTHING GREEN?

Computer: YES, THE GREEN PYRAMID.

Is the computer software actually learning something? It certainly simulates the process of learning. It knows that it can 1) do an action 2) admit the action is impossible, or that it can 3) answer a question in the affirmative or 4) answer a question in the negative or state 5) admit ignorance. But if you taught the computer thousands of different concepts (cubes, pyramids, pasta, cookies, ducks, stellar cartography) broken down into “blocks” of “knowledge” represented by “strings” – would the computer software actually be able to execute commands other than the 5 outputs available above? The simplifications of the world and the types of input-output available are too far removed from real-world abstractions and complexities to hold any weight.

I return to my Minecraft squirrel drama on the ledge. The squirrel program running inside Minecraft could be having a similar conversation to the one archived by SHRDLU :

Squirrel: I am sitting here.

Computer: You are indeed sitting here.

Squirrel: Should I move forward?

Computer: You should not. There is a vast ocean and you will drown.

Squirrel: Should I move left?

Computer: You should not. There is an ocean there too.

Squirrel: That sucks. Maybe I should move right?

Computer: Nope. Ocean all around, amigo.

Squirrel: Awww man. Shall I move backwards?

Computer: There is a block of earth there.

Squirrel: What about jumping? Can I jump onto the block of earth?

Computer: Alas, you can’t. There is a block of earth there too.

Squirrel: So… I should just sit here?

Computer: Sounds good to me.

The squirrel, like the SHRDLU program, takes “input” from the world (in this case, the computer is controlling what is in the world, but in the SHRDLU program, the world seems largely defined by the human-defined input.) The squirrel program is totally cool just sitting there, because it has gone through its programming and figured out that in order to stay alive (which squirrels in Minecraft apparently like to do) it should stay out of the water. The squirrel will never learn to dig through the earth or climb against the facade to get out. The program is quite content to execute its programming and chill.

So when I feel pangs of sadness that a squirrel is caught on the ledge, that is my human abstraction of what is going on. The squirrel program is actually quite happy where it is. But wouldn’t the squirrel also be quite happy to move around, too? When I’ve watched Minecraft mob patterns, I’ve noticed that almost all creatures feel an impulse to move around. If I unleash a pack of chickens into the wild, they’ll meander away eventually, often splitting off into different directions. Squirrels are similar, bounding away happily in the world. I have dug into the process of “artificial intelligence” in the mobs of Minecraft, I still feel the need to wonder – would the squirrel prefer to be moving, and does it consider that state ideal? I project the human emotion “happiness” onto the bounding squirrels and chickens of Minecraft – but could that be a fanciful description of something actually happening within the hardware.

While I know that aesthetically, I am sympathizing with the squirrels and chickens of Minecraft because they are kind of cute, I also have to wonder if from an artificial intelligence point of view, something deeper may be occurring under the surface. Of course, I can terminate the Minecraft program and walk away from the stranded squirrel completely. Brooks argues that “toys” offer too simplified a domain for serious study, and it is perhaps anachronistically futile to use an AI research paper from 1987 to contemplate upon Minecraft, a game released in 2009.

I am intrigued, reading Brooks, when he lists the engineering methodology behind building Creatures: “completely autonomous mobile agents that co-exist in the world with humans, and are seen by those humans as intelligent beings in their own right.” These artificial organisms would exhibit the following properties:

- Timeliness (as in reaction time)

- Robustness (minor changes in the properties of the world will not lead to a total collapse of the Creature’s activity or behaviour)

- Goals (the Creature should be able to maintain multiple goals, and, depending on the situation, prioritize one goal over another, as well as take advantage of fortuitous opportunities)

- Purpose (a Creature should do something in the world, should have some purpose in being)

In many ways, the Minecraft mobs satisfy these four requirements. The squirrel prioritizes staying alive over bounding about happily, the squirrel would jump up and try to flee if I hit it with my battleaxe, the squirrel reacts if I dig a path in the earth for it to escape the cliff and the squirrel has a purpose : it is a denizen of the forest, and makes the forest complete.

However, where Brooks and I may differ on interpretation of the concept of a Creature is in the words “co-exist in the world with humans” – players may enter the world of Minecraft, but are they really “in” the world of Minecraft? As pieces of software, does the squirrel program really “exist in the world” – is its physical existence as a tiny component of a hardrive a big detractor from its software, virtual manifestation?

The squirrel of Minecraft is an artefact running on the software foundations of a lot of artificial intelligence research. We can pause or “disable” the squirrel program, or the SHRDLU program, and when we re-engage the program it does not restart from scratch necessarily – depending on how Minecraft decides how mobs are loaded and respawned into chunks, that same squirrel may reappear, and reassess that it is still stuck between the ocean and a hard place. But is it really the same squirrel? Is it really manifesting a portion of intelligence? Would it prefer to be bouncing about happily rather than stuck on the ledge?

Or is this all besides the point – is the more interesting investigation with regards to how the player responds to the situation. So I ask you the question: if you found the squirrel stranded on the ledge, would you do anything about it? And why?

The post A Squirrel Is Stuck Between An Ocean And A Hard Place appeared first on &.

]]>The post Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context appeared first on &.