The post Bootcamp: Trees appeared first on &.

]]>I am a firm believer that the history of Québec is a collection of paradoxes and contradictions dressed in settler-colonialist and nationalist-driven social and political development. As a scholar deeply concerned with engaging in revisionist histories of Québec, I decided this week to take on a text that has plagued me for the past few years: A Short History of Quebec, Third Edition by John Dickinson and Brian Young. This text is often regarded as a cornerstone text in most studies and university courses on the province. I, however, take serious issue with the text.

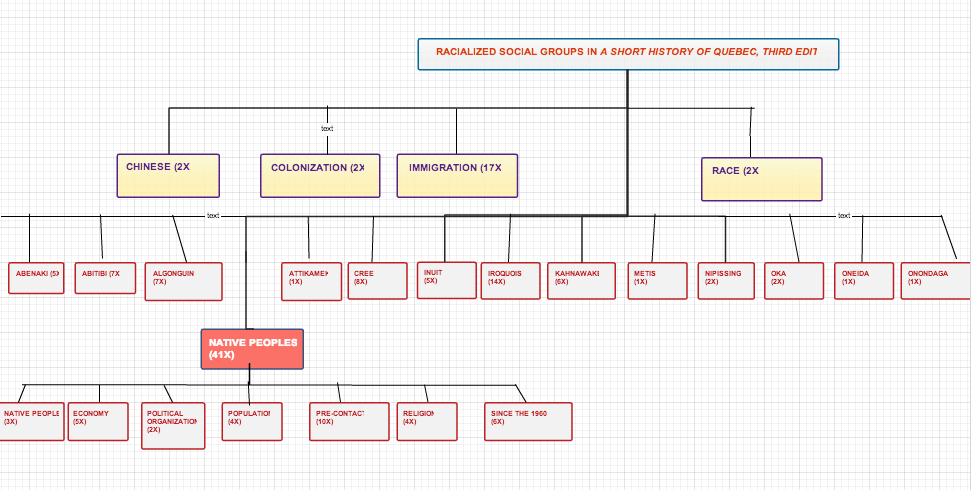

Let’s face it, history is often written by those in power: white, heterosexual men. I have no problem with this, unless it results in the marginalization or erasure of other historical narratives. For this bootcamp, I have decided to re-construct the index of A Short History of Quebec in a tree diagram, with a particular focus on references to racialized social groups.

I must admit that I am absolutely inept at constructing diagrams. The only diagrams that seem to make sense to me are maps. While the visualization of the references to racialized social groups seem clear to me, I am sure this tree diagram may seem like a mess to someone else. If the tree diagram is supposed to present a concise diagrammatic representation of information, where did I go wrong (or right)?

Here is a breakdown of the information from the text:

| Chinese |

2 |

| Colonization |

2 |

| Immigration |

17 |

| race |

2 |

| Abenaki |

5 |

| Abitibi |

7 |

| Akwesasne |

2 |

| Algonguin |

7 |

| Attikamek |

1 |

| Cree |

8 |

| Erie (Native people) |

2 |

| First Nations (see Native people) | |

| Indian Act (1876) |

1 |

| Inuit |

5 |

| Iroquois |

14 |

| Kahnawake |

6 |

| Métis |

1 |

| Native People |

41 |

| Nipissing |

2 |

| Oka |

2 |

| Oneida |

1 |

| Onondaga |

1 |

Moretti reconfigures the tree diagram as a methodology for demonstrating “the interplay between history and form” (43). This is precisely why I decided that a tree may be an ideal medium to explore my contention with this particular history text. While the frequency of references are clear, as well as the sub-categorization of Native Peoples, I continue to feel that the tree does not articulate the lacuna of references to racialized peoples in a history text of Québec lauded to be the most comprehensive. We can see from the tree that there are a total of 106 references to Native/First Nations/Indigenous Peoples. There are no references to any other racial group other than Chinese (2 references). There is something amiss here…can the history of all other racialized groups fit neatly into the two references on race? While the numbers clearly explicate this situation, I continue feeling that the tree remains incomplete somehow.

Maybe the tree does not work alone..and must be juxtaposed with another three to references to other texts on racialized peoples in Québec—but the problem here is that these other texts generally do not factor into the discourse of Québécois history. I am concerned with the fact the A Short History of Quebec represents a very myopic presentation of racialized people in Québec.

In this bootcamp, I relied specifically on analyzing the index of A Short History of Quebec, and this source may present some insight into my dissatisfaction with my tree. The index of the text relies upon noting “important” keywords, however these keywords remain wrapped in a system of classification that may distort my understanding of the text. Moretti argues that a language tree “is a way of sketching how far a certain language has moved rom another one, or from their common point of origin” (46). In some ways, this tree is related to that language tree…but there is no indication of common points of origin, or history for that matter, only frequency. This issue of language and classification leads me to think about Deleuze’s image of the archivist. Who has given the archivist the power to organize the archive, to classify and name the documents? In relation to Foucault’s Archeology, Deleuze posits that “the words, phrases, and propositions examined by the text must be those which revolve round different focal points of power (and resistance) set in play by a particular problem” (Deleuze, “A New Archivist,” 17). I am not sure if the tree diagram I constructed summarizes the focal points of power (and resistance) I am attempting to address in A Short History of Quebec. Maybe the index has lead me astray, or maybe I simply need to take a workshop in graphs and diagrams…either way, I still think that it is clear that a “comprehensive” history text of over 400 pages should have more than two references to race.

Works Cited:

Deleuze, Gilles. “A New Archivist” Foucault, Trans. Hand, Séan. London: Althlone, 1988. 1-22.

Dickinson, John and Brian Young. A Short History of Quebec, 3rd Edition. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Moretti, Franco. “Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History–3”. New Left Review 28 (July-Aug 2004): 43-63.

The post Bootcamp: Trees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Out on a Limb with Branching Narratives appeared first on &.

]]>Where are the procedural boundaries of an infinite story?

How does the invisible render the visible meaningful?

Is the true tree-narrative actually the structure of a network?

Branching narratives are less objects than they are procedural systems. Usually when we talk about nonlinear, branching storylines, we think of either the popular Bantam line of Choose-Your-Own-Adventure (CYOA) gamebooks or video games with multiple endings based on the ethical decisions characters have made throughout the game’s story. But in truth the tradition goes further back than this, all the way back to the Dada movement. It was in the 1920s that Dadaist Tristan Tzara first suggested creating a poem by cutting up words from the newspaper and mixing them together before drawing them from a bag one by one to create a new piece of verse. (Tzara VIII) Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs would later adapt this practice into what they called the “cut-up method”; and while it may sound like poetry created through a system of randomness removes all choice from the hands of the participating user (rather than ‘readers’ or ‘writers’), what’s important here is the existence of multiple possibilities at every moment. Just like a choose-your-own-adventure story, the user doesn’t necessarily know what’s next, what effect her next decision will really have. The central difference between cut-up poetry and CYOA books is that in the latter the user believes she has a slightly better idea of outcome. This is because at every fork in the CYOA narrative, she’s given one of several options, whether to reason with an attacker, turn tail and run, or maybe fight back. But this autonomy extends only over a given character’s decisions (usually the protagonist’s), not how the reality of the narrative will treat these decisions (it could be doing something relatively safe like picking up a phone turns out to spell doom for the story’s hero, quite incomprehensibly). In the cut-up, the user has no idea what will come up next, but with a good enough memory, every new branch on the tree will come up as familiar, because it’s the user who cut up all the words in the first place. Furthermore, the procedural nature of both the cut-up and the CYOA story both allow for replay to increase the chances of cognitive profit. The user is scripted by the environment of the rules as well as able to act upon it; at every wrong turn, she’s reminded of the multiple possibilities of the moment, “in which all the quantum possibilities of the world are present.” (Murray 7) The user can experience all these possibilities if she chooses to, without necessarily privileging any given one as the single choice.

A CYOA diagram of Journey Under the Sea by Michael Niggel. For a blow up click here: CYOA-Michael-Niggel.

Another strain of thinking might treat methodological examples like these as what’s commonly known as interactive fiction (or IF), a term most often applied in thinking about games. From text experiences like Adventure to role playing games like Dungeons and Dragons to AAA studio releases like Deus Ex or Fable, in most interactive fictional experiences, just like in most CYOAs or cut-ups, it’s the author/programmer who lays out all the possible passageways, constructs the architecture of the experience, but it’s always supposed to be the user who does the navigating. The following of the twisting path controls the revelation of the narrative, consequently proposing the argument that the narrative is actually generated by the interactive process (Montfort 3). But does this make for a true branching narrative? The real tree structure may have no ending, and a game can only contain so much code, a book can only contain so many pages, and a bag can only contain so many cut out words. Because of the limits of programming, most branching narratives (both digital and analog) tend to resolve the issue of infinity with convergence, the same type that Moretti talks about with Kroeber’s Tree of Human Culture (Moretti 54). A lot of the time in branching narratives, different choices made at different points will lead to the same conclusion. This means in the CYOA book the pure tree structure of the story is a bluff: the user can’t have two choices on page a that both take her to page c, but she can have one that takes her there from page a and one that takes her there from page d. In games it’s even harder, mostly because to build a game is so very difficult and time-consuming. The popular open-world Fable franchise, for example, in part built its original reputation on the promise of user ethics affecting game-character and narrative—in a given situation the player could choose to do the ‘good’ thing or the ‘evil’ thing. However, more often than not both choices yielded the same or extremely similar results for the player’s advancement in the game and the overall story; the real differences were in the game hero’s appearance, the shabbiness of the environment, and the player’s emotional experience (and even this is a subjective claim). However free Fable may claim to be (“the options are obvious – the decisions are up to you,” claims Fable III’s slipcase jacket), the game actually only offers a very narrow range of pathways.

While your ethical choices control the look of Fable‘s protagonist, the narrative outcomes are largely the same. Image from Fable Wiki.

Space restraints keep me from going into more elegant examples of IF (any one of which would take me a long time to unpack, and Nick Montfort’s already done it better than me anyway). Suffice it to say that the real branching storyline is one written entirely by the user, and so far, the few examples that exist are arguable at best. Certainly truly nonlinear rarely even have stories articulated further than ‘goals’. (Sorens 4)

In any full branching narrative, the options have to be connected together so that the user ends up caught in a maze rather than making her way through the splitting veins of a boundless organism. Even Borges’ Garden of Forking Paths is just that: a garden where every point leads to every other. It’s a hedge maze—huge, but hardly infinite.

In a branching narrative, most continuity problems are solved by occasionally routing multiple decisions to the same point for the sake of finitude.

So the truth about the tree is that it’s not a tree. It’s a network, with not a trunk but rather occasional central points where things gather up or channel together. The tree is the chronology of your own starting mark, that point of entry from which you began the exploration. Even Moretti alludes to this no later than his introductory paragraph:

Theories of form are usually blind to history, and historical work blind to form; but in evolution, morphology and history are really the two sides of the same coin. Or perhaps, one should say, they are the two dimensions of the same tree. (43)

Without time and your participation, a tree can’t look like a tree. It’s the same in data analysis as it is in evolution. So history is the crux of the tree’s usefulness as a methodological tool. However, Moretti also ties the passage of time necessarily to evolution; he doesn’t take into account the possibility of wasting time. These are the notions I found myself starting to suspect: First, the inferred proposal that trees can be useful without time (I believed that the flattening of the temporal dimension in a tree would render it instead a network and reveal all the ‘branch’ lines that a history-centric view had rendered invisible), and once that was resolved, the idea that the passage of time always subtends evolution. It’s a concept problematised by the existence of convergence, and if you think in terms of networks, then potentially everything is a result of convergence before anything has a chance to diverge. Conversely, Moretti tells us that convergence only arises on the basis of previous divergence, so it seems that it’s a chicken-and-egg argument: all things are products of other things coming together, but those things had to come from somewhere too, and any genealogist will tell us we can only trace the lineage so far back.

Jason Shiga‘s April Fooled.

But on to our final branching narrative (and simultaneously back to wasting time—convergence at play). It seems to me that the best way to illustrate the tree’s network nature, much more akin to Kroeber’s tree of culture than even Moretti’s diagram shows, is to look at a tree within a network of convergences—a social network. What narrative forks and branching more than the personal one you access every time you explore your Facebook feed and meander your way through the never-ending stream of posts? None of it follows from any logic but your choice—it’s the story of how you spend your day peppered with the occasional contribution (or recapitulation of someone else’s contribution). Like every other branching narrative, what’s made present can only be constituted by what’s rendered absent, invisible. You can’t follow every pathway and click on every link; I once tried to just expand five years of posts on my wall (without even following any of the links), and it took me nine hours. (Sinervo 2) We finally have the potentially limitless story, even if it is a story as disorganized as the Internet, but we’re bounded by our own abilities as readers. More importantly, just like all the other branching narratives, this one is a network, and one where our most consistent decision is to double back on the branch we’re hanging from – after all, the back button always need to be clickable before the forward one.

WORKS CITED

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Garden of Forking Paths.” Labyrinths. Trans. Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby. New York: New Directions, 1962.

Burroughs, William S. and Gysin, Brion. The Third Mind. New York: Seaver Books, 1978.

Crowther, Will, and Don Woods. Adventure. PDP-1/FORTRAN. Numerous publishers, 1975-1976.

Eidos Montreal. Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Square Enix, 2011. Xbox 360.

Lionhead Studios. Fable III. Microsoft Game Studies, 2010. Xbox 360.

Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages: an Approach to Interactive Fiction. London: The MIT Press, 2005.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63.

Murray, Janet. “From Game-Story to Cyberdrama.” First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Ed. Noah Wadrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. London: The MIT Press, 2004.

Sinervo, Kalervo A. “A Never-Ending Exercise: Facebook as an Apparatus of the Incomplete Self.” Unpublished article. Montreal, 2010.

Sorens, Neil. “Stories from the Sandbox.” Gamasutra. 14 February 2008. Web. 31 October 2013.

Tzara, Tristan. “Dada Manifesto on Feeble Love and Bitter Love.” 391. 12 December 1920. Web. 1 November 2013.

The post Probe: Out on a Limb with Branching Narratives appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Deep Roots and Knotty Branches: Tree Diagrams and Irish Traditional Music appeared first on &.

]]>How may tree diagrams deepen our understanding of cultural phenomena?

Are some forms of knowledge better suited than others to “tree-ish” representations?

Francis O’Neill was born in 1848 in Tralibane, County Cork. He would sail the world as a crewmember on a British merchant ship before settling in Chicago, where he eventually rose to the position of Superintendent of Police. Francis O’Neill is best known as a collector of Irish traditional music, as one of the men who “saved” this music. He published a number of collections between 1903 and 1922: O’Neill’s Music of Ireland; The Dance Music of Ireland; O’Neill’s Irish Music: 250 Choice Selections Arranged for Piano and Violin; and Waifs and Strays of Gaelic Melody. This probe will focus on the first and most renowned and influential of these collections: O’Neill’s Music of Ireland.

The collection contains 1850 tunes, and is colloquially known as O’Neill’s 1850. Each tune in the collection is listed with the sheetmusic notation, the tune’s title (in English and in Irish Gaelic), and, where available, the name of its contributor. Contributors to the collection include Francis O’Neill himself, others members of the Chicago Irish Music Club, such as James O’Neill, Bernard Delaney, John Ennis, Edward Cronin, and John McFadden, and other miscellaneous contributors. Of the 1850 tunes, 419 have no named contributor or source. In Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, one of the many books O’Neill wrote about the music he sought to save, he explains that “[w]here no names were appended their absence indicated that such tunes did not come into [his] possession from individuals” (O’Neill, 65). It is not clear what O’Neill meant by this. O’Neill did occasionally acquire tunes that already existed in written form (Carolan, 34-35); the tunes with no explicitly stated source may have come from manuscripts.

Tunes with known contributors (Francis O’Neill, James O’Neill, John McFadden, and James Early).

Tunes with no contributor indicated

It is worth emphasizing that the contributions to the collection converge on Francis O’Neill, who ultimately decided which ones to include. Plotting out a tree of contributors to the 1850 would certainly be feasible, with a node at the name of each contributor branching off into all the tunes this individual contributed, and all of these tunes in turn converging back onto a node representing Francis O’Neill as the main editor and collector. An “unknown” category could perhaps be created for the 419 tunes that are listed with no named source. However tracing the origins of each tune past the names of their contributors – say, tracing a genealogy of the tunes’ transmission over a 50- or 100-year timespan – would be exceedingly difficult. The origin of Irish tunes is a highly contentious issue, as O’Neill himself acknowledged:

Irishmen from all parts of Ireland intermingle promiscuously in all countries to which they migrate and the man from Ulster soon learns the Munster man’s music, and so on until the fact of obtaining an air or tune from a native of a certain county or province carries with it no assurance that the music was not learned from a stranger or chance acquaintance (O’Neill, 66).

This matrix of tune transmission through time and space may be as convoluted as the Celtic knot designs on the front cover page of the 1998 reprint of O’Neill’s collection. Indeed the designs’ interconnecting, overlapping and crisscrossing lines seem to harken to an apocryphal tale often told in Irish traditional music sessions. In this tale a well-known elderly fiddler passing through a town or village teaches a tune to a younger local fiddler. A few years later the old fiddler returns, and the younger one enthusiastically plays back the tune the old man taught him. The old fiddler leans in and says: “That’s a nice tune. Can you teach it to me?”

Other factors further complicate the situation. For example, human error is rampant in collection endeavours of Irish traditional music.

After James [O’Neill] had noted a tune to his own satisfaction, Francis [O’Neill] listened to his playing of it and, relying on his acute ear and encyclopedic memory, passed final judgement on it. He did not know that James was sometimes playing correctly what he had inadvertently written down incorrectly (Carolan, 41).

Francis O’Neill himself believed that “[t]he classification of Irish melodies is to a certain extent arbitrary, as dance tunes are not infrequently used as airs for songs and marches, and vice versa” (O’Neill, 86). Other attempts to categorize and plot out Irish traditional music have run into a similar quandary. Ethnomusicologist James Cowdery has applied tune-family theory to Irish traditional music. Yet even Cowdery acknowledged that music tends to evade strict categorization: “…the use of [the tune-family theory] can lead us into a thicket of melodic relationships coherently without forcing tunes into final categories [emphasis added]” (Cowdery, 94). These forces – musico-geographic miscegenation, human error and the music’s evasion of categorical parameters – all exemplify Moretti’s notions of “divergence” and “convergence.”

Divergence prepares the ground for convergence, which unleashes further divergence: this seems to be the typical pattern. Moreover, the force of the two mechanisms varies widely from field to field, ranging from the pole of technology, where convergence is particularly strong, to the opposite extreme of language, where divergence…is clearly the dominant factor…Because if the basic mechanism of change is that of divergence, then cultural history is bound to be random, full of false starts, and profoundly path-dependent: a direction, once taken, can seldom be reversed, and culture hardens into a true ‘second nature’ – hardly a benign metaphor. If, on the other hand, the basic mechanism is that of convergence, change will be frequent, fast, deliberate, reversible: culture becomes more plastic, more human, if you wish. But as human history is so seldom human, this is perhaps not the strongest of arguments (Moretti, 55-56).

In light of Moretti’s insights, O’Neill’s 1850 may be interpreted as an instance of a cultural hardening, a point of cultural convergence, the creation of a true “second nature,” to borrow Moretti’s phrase. This first collection became a node for the transmission of Irish traditional music both in time and around the world, thus enacting a phase of divergence. It also spawned offshoots, additional branches in a metaphorical tree. O’Neill’s next collection – The Dance Music of Ireland, published in 1907 – was designed specifically for “musicians who were interested only in dance music and who needed a cheaper and more focused publication that the deluxe hardback of 1903…” (Carolan, 46).

The Cabinet of Horrors

People have generally sought to explain cultural change and cultural variation by supposing that culture is causally driven by something else (the climate, the social structure), or, more strongly, that it is adapted to something else, or, more strongly yet, that it functions adaptively for the benefit of something else (here social structure, or ruling classes, are favored as suspects over the climate). This has led to an awful lot of (if I may use the phrase) adaptationist just-so stories, and uncritical analogy-mongering on a level with the sort of thinking which leads rhinoceros horn to be prescribed for impotence (Shalizi, 121-122).

While Shalizi considers factors – climate, ruling class, etc. – that relate tangentially at best to O’Neill’s collection work, the subtitle “Cabinet of Horrors” seems an appropriate moniker for O’Neill’s collection work in light of some of its methodological deficiencies. For one, O’Neill claims to have selected only “[t]he best settings [of tunes for his collection], representing all varieties…” (62). The notion of “the best” in any field of cultural practice is highly subjective; cynics might legitimately suggest that O’Neill’s choice of tunes for Music of Ireland and subsequent collections – perhaps having been based on his own personal aesthetic preferences – may have relegated a number of old tunes to oblivion. Furthermore, in at least one known instance, O’Neill filled in the gaps for a tune he could only partially remember. He had learned “The Woods of Kilmurry” from his mother’s singing during his youth, but decided to compose those parts of the tune he could not remember before including it in his collection (O’Neill, 69). This tune does raise issues of methodological integrity, however moot it may be to blame Francis O’Neill given the inherent fluidity of Irish traditional music. One may also wonder how “The Woods of Kilmurry” might be represented in a tree diagram. With a broken, zigzagging line? With sections of the branch in different colours to indicate some creative filling-in?

The questions considered in this probe highlight the paradoxical nature of Irish traditional music as both a definable practice – insofar as tunes, practitioners, contributors and sources can be accurately identified and labeled – and as a fluid one that evades linear, causal representation in the form of a tree diagram. Anyone attempting to represent this tradition in such a diagram would have to take both aspects into consideration.

Works Cited

Carolan, Nicolas. A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago. London: Ossian Publications, 1997.

Cowdery, James, R. The Melodic Tradition of Ireland. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1990.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3”. New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63.

O’Neill, Francis. Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, with some account of allied subjects including O’Farrell’s Treatise on the Irish or Union pipes and Touhey’s hints to amateur pipers. Edited by Barry O’Neill. Darby, Pennsylvania: Norwood Editions, 1973.

Shalizi, Cosma. “Graphs, Trees, Materialism, Fishing.” Reading Graphs, Maps, Trees: Responses to Franco Moretti. Ed. Jonathan Goodwin & John Holbo. Anderson: Parlor Press, 2011. 115-39.

The post Probe: Deep Roots and Knotty Branches: Tree Diagrams and Irish Traditional Music appeared first on &.

]]>The post Musical Trees appeared first on &.

]]>Boot Camp – November 7

The German-Swiss poet Hermann Hesse once wrote, “Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.”

I have always had a great appreciation and fascination for trees. As a child, my favourite thing to do was explore the “Fairy Glen” in Scotland, listening for the fairies hiding in the trees and waiting to hear or see some form of life within the forest. My love for trees and their powers led me to name my most recent musical project “Tree Talk” . For this week’s boot camp I decided to make a tree diagram from a collection of Newfoundland and Labrador Fiddle Tunes by Newfoundland musician Kelly Russell.

His collection took place between 1970-1980 with Canada Council funding. Russell concentrated his collecting on the west coast of Newfoundland and Labrador because he knew there were many fiddlers living on the West of Newfoundland and Labrador. He makes note in the introduction that he does not claim to have visited every fiddler, but he believes his collection is an accurate representation of the music being played in these areas at that particular time.

Most fiddlers were between 50-70 years old, and many passed away before the publication of the book (2003). He would show up to towns and ask, “Does anyone around here play the fiddle?” Being a well-known personality gave Russell easy access and welcomed attitudes in each new town and village he visited.

He believes that there was once a broader musical tradition that has died out in most areas of Newfoundland and Labrador, and feels as if his collection documents the last remains of this tradition. The difficulty in tracing sources of tunes was a challenge, and Russell is unaware of many sources of tunes he collected, as were the players themselves. Many also did not know the names of tunes they played, which resulted in titles printed in the book such as “Old Reel #3.”

Mapping out this collection could have gone in many directions. Did I want to visualize the amount of tunes from a particular region? Or perhaps specify the particular types of tunes found in each region? Did I want to focus on the individual fiddlers and their contributions to the collection? Or the keys that the tunes were played in? I drew my tree diagram to first show the six geographic areas Russell collected from, and then broke it down into the different fiddlers from those regions, and finally to the amount of tunes they contributed to the collection by type of tune (reel, jig, waltz, etc.).

Another factor making this collection difficult to graph is the fact that many fiddlers played the same tunes, but he only published them once under one fiddler. It is not specified which other fiddlers shared the same tunes, so the most popular ones are not noted. If one were graphing the music by geographical region, the data would not be accurate due to the lack of specificity of players and tunes. Depicting the shared tunes in a tree diagram would be a wonderful method of showing the interweaving of tunes from one place or person to another.

Moretti says, “A tree can be viewed as a simplified description of a matrix of distances,” and that they are “a way of sketching how far a certain language has moved from another one, or from their common point of origin” (46). I would propose taking Russell’s collection further and finding the original rooting places of fiddle tunes and tracing how they moved geographically from one place to another over time. Simply tracing what was being played at one point in time in particular areas is an interesting snapshot, but the interesting data behind it would be very useful information. Plotting out this tree diagram resulted in me having more questions rather than feelings of satisfaction.

I have drawn on a blank map of Newfoundland and Labrador the six areas Russell collected from, and indicated the number of tunes published from each region. Seeing the actual geographic space each region takes up on a map makes me realize how much of the province he did not collect from, and how varied the areas are in size and location. For example, he collected fifty tunes from the tiny area of Stephenville/St. George, but only forty tunes from Labrador, which is massive in comparison. Russell collected from four fiddlers in both of those regions, but is there a reason that the repertoire is larger in Stephenville/St. George than in Labrador?

Just for fun, I graphed the number of tunes by geographic location, matching the colours from my map and tree diagram. NL graph

I thoroughly enjoyed this week’s boot camp and readings, and being able to critically examine this collection, which has been a major part of my musical life. I hope to take the investigation further and to find answers to some of my many unanswered questions.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63. Print.

Russell, Kelly. “Kelly Russell’s Collection: The Fiddle Music of Newfoundland & Labrador, Volume 2, All The Rest.” Trinity, Newfoundland: Pigeon Inlet Productions Ltd, 2003. Print.

The post Musical Trees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Talking Trees appeared first on &.

]]>Probe for Nov. 7

Given the extent to which tree structures have permeated computer science (think of the way the files are organized on a computer, or the nested windows and menus used in software applications), it’s no surprise that we find them everywhere in digital games. Some appear in the form of tree diagrams, others are hidden or disguised. Not all of these trees are “true” trees, according to the strict definition of the word as outlined in graph theory, but the very fact that we call them by this name suggests that these mutants occupy at least some of the same conceptual terrain as their undirected, non-cyclical sisters.

One of the most interesting examples of trees I’ve encountered in games so far is the realm tree in Crusader Kings II, which provides players with a visualization of the feudal hierarchy that is so essential to the game. The tree resembles an organizational chart, depicting the chain of command from emperors down to barons, mayors, and bishops (peasants don’t make the cut); it also, importantly, indicates their opinion of your character, and your character’s opinion of them (the green or red numbers by their portraits), as well as what percentage of the realm’s total troops they control.

Screenshot of the realm tree from Crusader Kings II. My character is Zegota, at the top or root of the tree.

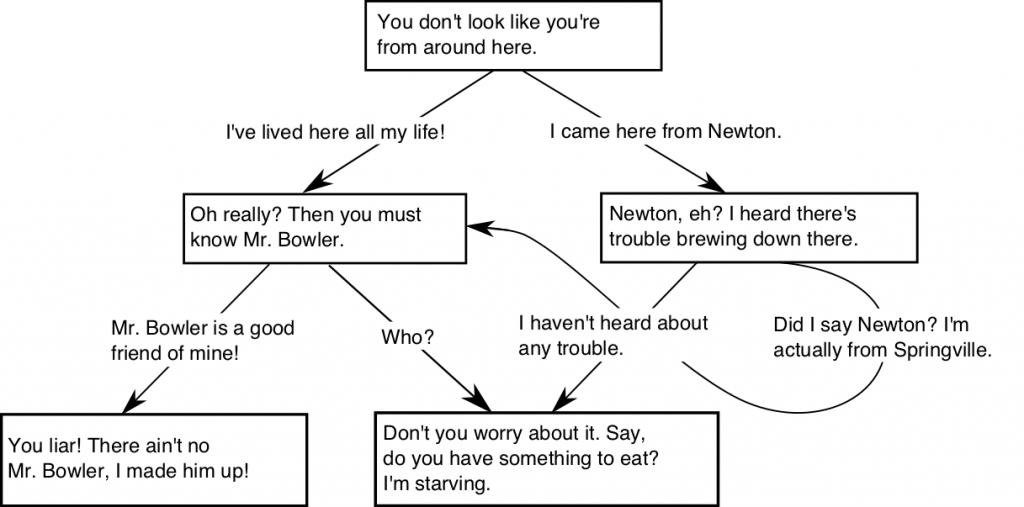

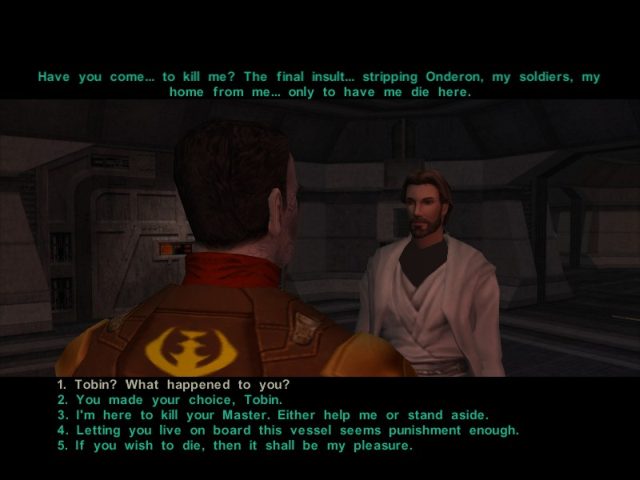

Other trees are much less visibly “tree-like” than this one however, at least from the point of view of the player. For example, one of the staples of digital role-playing games and adventure games is the so-called dialogue or conversation tree.

The term refers to the branching structure employed in games such as Dragon Age: Origins, the Walking Dead series, and Grim Fandango. However during conversations the branches (the links connecting parent nodes to child nodes) are invisible to players, who are instead confronted with a list of options indicating potential responses. Selecting one of these options leads to another list of responses, which leads to another, and so on, until the conversation comes to an end.

For some players even a limited number of choices can impart a sense of agency or individuality, enhancing moral or emotional investment in the game by allowing them some say in how the story unfolds—or at least that’s the idea. For developers, however, structuring dialogue in this way can also be extremely labour-intensive, particularly if each response is fully animated and voice-acted. Constraints such as budgets and fixed release dates often force developers to merge branches together so that different choices lead to the same outcome or event. As a result typical dialogue trees are much more akin to Alfred Kroeber’s tree of human culture, with its multiple points of convergence, than they are to the ever-diverging tree of life (Moretti).

In an effort to reduce the scope of the game developers may also restrict the number of options available at each juncture to a set of “logical” or “expected” choices. In many cases these choices seem to be constructed with a particular audience in mind. They may also reflect the personal biases of the developers. For instance, in the games that I’ve played, moral choices often consist of deciding whether or not to kill a character (or which character to kill), and the option to give an object appears much less often than the option to receive.

In an effort to reduce the scope of the game developers may also restrict the number of options available at each juncture to a set of “logical” or “expected” choices. In many cases these choices seem to be constructed with a particular audience in mind. They may also reflect the personal biases of the developers. For instance, in the games that I’ve played, moral choices often consist of deciding whether or not to kill a character (or which character to kill), and the option to give an object appears much less often than the option to receive.

While the trees examined by Franco Moretti are figured as representations or tools that help us to make sense of the past (and to some extent the present), dialogue trees are more clearly oriented towards the future. They are not only descriptive, but also prescriptive, both in the sense that they can be used to guide the development of a game, and in that when implemented, they restrict the field of possibilities within a game to a selection of relatively fixed options. Jacob Harley argues that, “the steps in making a map – selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and ‘symbolization’ – are all inherently rhetorical” (11), a statement that might just as easily be applied to trees. As organizational structures articulated through diagrams and code, dialogue trees are part of the matrix of explicit and implicit rules that determine what can be done and what can be said within the space of a game. As such their disconnections and exclusions interest me as much as what they make visible or possible.

These positive and negative spaces only really begin to take shape, however, when we look at large numbers of dialogue trees, rather than focusing on individual examples. Just because one game doesn’t allow the player character to directly engage in same-sex relationships does not mean that this game, or any other like it, is necessarily heteronormative. But when the vast majority of videogames omit this option, when as a whole they refuse to acknowledge even the possibility of anything other than heterosexual desire, then we can begin to talk about heteronormativity as a process of systematic exclusion, discrimination, and normalization.

At least some of the negative spaces will occur as a result of technological limitations, and understanding where these limitations arise is no less important to our comprehension of dialogue trees than are the images or words on the screen. There are many reasons why developers have continued to represent dialogue as a series of multiple-choice questions, despite all the advancements that have been made in other areas (Sinclair). If dialogue trees are a matter of determining what leads to what, of setting up causal relations, then perhaps we should apply this logic to the trees themselves by asking what factors contributed to the widespread, persistent use of dialogue trees in certain genres. From there we can start to ask questions about how dialogue trees relate to particular notions of choice and agency in, for example, consumer culture and multi-party democracies. What does it mean to operate within a system that reduces choice to a list of several pre-determined options? Does it matter if the difference between options is only superficial? How do players resist, escape, or subvert such a system? What roles do imagination and representation play? How do dialogue trees relate (or not) to other structures and mechanics within a game? How is power distributed and enacted? Of course I have no answers to these questions, but then this is just a beginning, one among many.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63. PDF.

Harley, Jacob. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26.2 (summer 2919): 1-20. PDF.

Sinclair, Brendan. “Taking an axe to dialogue trees.” Gamespot, Oct 5, 2010. Web. http://www.gamespot.com/articles/taking-an-axe-to-dialogue-trees/1100-6280781/

The post Probe: Talking Trees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>Bootcamp + Trees + Nov 7

“There is a constant branching-out, but the branches also grow together again, wholly or partially, all the time.” – Alfred Kroeber, Anthropology

Experiencing our class thus far, I must say it’s been less painful then expected to get my mind inside the theory circle. Once I became familiar with the ‘big names’ and most of the prevalent terms and ideas, everything became much easier. The circulatory nature of theory in the Humanities is evident as you read repeated names and quotes cited in each of our readings. And, as the semester has worn on, it has already become clear to me who speaks loudest to my sensitivities, my ways of working and my intuition. I have favorites: theorists I’ll keep tabs on and those I probably won’t. It’s the same for them. Some drool over Foucault while other go for Delueze and Guattari.

Franco Moretti had me at ‘graphs’.

This last series of Graphs, Maps, Trees is right up my alley because I am an intensely visual learner and communicator. Moretti gave us darn good reasons as to why this use of quantitative data and its visual representation add something to the textual humanities and can give us a new way of seeing. Of Graphs, Maps, Trees, I’m most interested in Trees. It probably has to do with my subject of study and its long lineage or my penchant for trees themselves. The graphs here feel less rigid, more organic and illustrate the more ‘messy’ bits of quantitative data better. Either way, I knew it was the perfect form for my latest question: the lineage of thought.

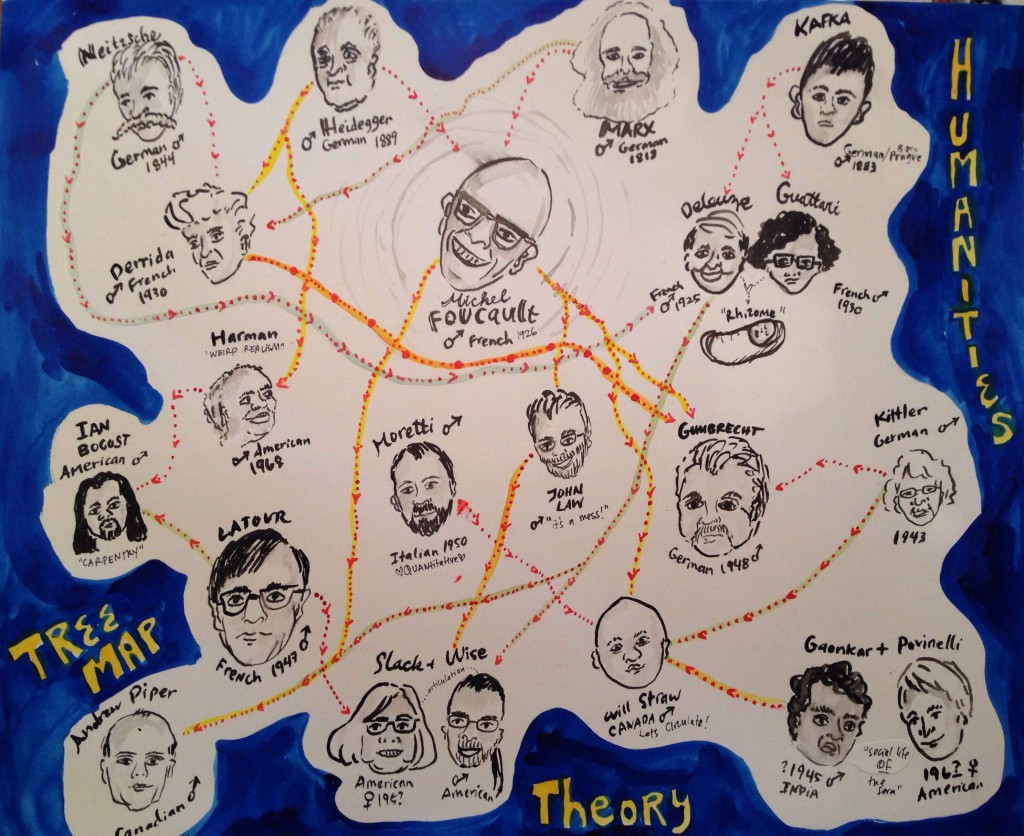

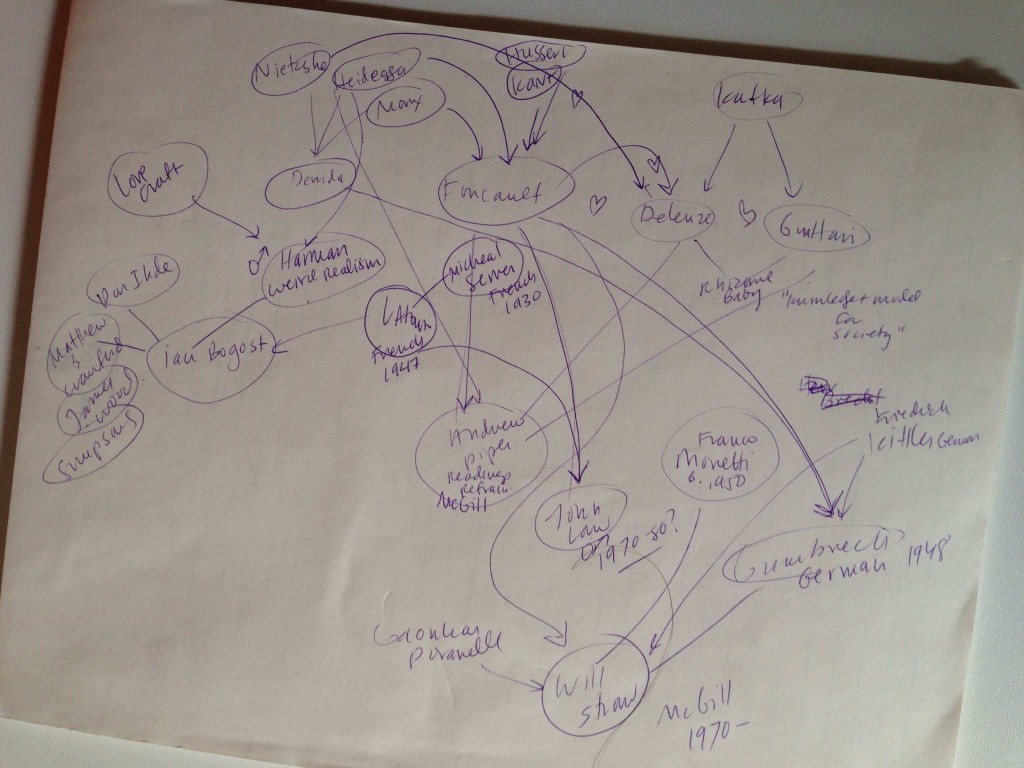

For this week’s Bootcamp, I’d like to experiment with our own syllabus. Who/what are we reading and what did those people read? How is the flow of theory/knowledge passed down to us and how do we become a part of it? Who inspired those who inspire me?

So, I made a tree graph.

I chose to do this with my own artistic interpretation because 1) I’m horrible with computer programs, 2) It’s dead fun to cartoonize the serious theorists we’ve been reading*, 3) We can see how the cartographer’s bias can influence our interpretation of the information. My method was similar to Moretti’s method of plotting Hamlet in next week’s Network article: I went through all of the readings and marked down each writer’s direct positive references within the articles we’ve read. If there was no obvious citation, I went online and did a search to see who their biggest influences were. I, by no means, exhausted these articulations. Sadly, I had to make many omissions and simplifications in order to fit it on the page. JP Harvey’s Deconstructing the Map and its warnings about the cartographer’s inherent bias is well taken.

My initial plotting of the theorist tree:

Although it looks like a network graph, it’s really a tree: I loosely placed them from oldest (top of the page) to youngest (bottom of page). And even though it’s messy – it actually does help me see things:

- If you want to be a theorist in the Humanities, you should probably grow a mustache.

- Foucault is by far the most referenced writer in our readings.

- There are other prominent authors that reference within the Humanities less but are referenced more (Moretti, Latour). Does this speak to writing style or more independent or interdisciplinary thought?

- If you do this long enough and are awesome at it, you will come to be referenced by last name only. Also, if you are in collaborative pair.

- Weirdly, there is little symbiotic sharing of intellectual love (other than the collaborative pairs). Most of this seems to simply be because of generational spans.

- At first glance, I thought: of course, it’s all a bunch of white guys from Germany and France. But if you look more closely at the ‘generations’ from top to bottom, you can see that even just in the last 50 years, the field has become much more diverse. I’m not sure if this speaks to the field at large or if Darren has just done a good job of making a point to include these scholars.

To place myself within the spaghetti dinner of thought, I’d probably plop myself down right below Moretti, John Law and Slack and Wise. I feel comfortable there in all directions: Mess, visual representations the present new information to the humanities and Articulations and Assemblages. Interestingly, these scholars are inspired by some of the others that I simply can’t get into – but now, seeing the lineage, feel closer to.

What do you see? Can you see anything at all? Does it help to clarify things or just confuse you? What does humor do to the information? Where are your pathways?

*Making Foucault look like the evil mastermind in the middle was a bit of an accident. Or was it?

And, just for fun, the winning mustache goes to: Nietzsche.

The winning overall hairstyle: Marx.

References:

Goodwin, Jonathan, and John Holbo. Reading Graphs, maps & trees: responses to Franco Moretti. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2011. Print.

Harley, J. B., and Paul Laxton. The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. Print.

Moretti, Franco. Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for a literary history. London: Verso, 2005. Print.

The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Tree Map, Murder, and Mayhem in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus appeared first on &.

]]>

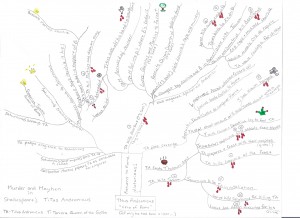

It looks like a tree, but I meant for it to be a map. I wanted to map out Titus’ destructive decline in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. Titus Andronicus is my favourite Shakespeare play. The murder and mayhem is unrelenting and shocking. The first time I read the play I kept going back and forth in the text to count how many people had died. When I reread the play for the bootcamp, I was shocked anew by the brutality exhibited by the characters. I chose Titus Andronicus because I finally wanted to decide, for myself, the reason why Titus’ life goes downhill in such a spectacular manner. Is it the fact that he is a victorious general and therefore a threat to Saturninus? Is it his refusal to show mercy by ordering Alarbus, the oldest son of Tamora Queen of the Goths, dismembered? Or is it his overweening devotion to Rome that supersedes even familial ties? Or all of the above? Who does most of the killing? This play would have actually been great to graph (who kills and how many they kill, how they kill, percentage of characters left alive at the end…). I had originally wanted to “map” out the progression of the play hoping that a visual representation would shed some insight on it. Then I realized that mapping, according to Moretti, involves actual maps and distances, and that what I was creating was a tree (once I read Moretti’s third article). The tree allows me to visualize the play without having to flip back and forth between pages. Creating the map revealed quite clearly that there are three main branches to the story. First, that a triumphant Titus is a threat to Rome’s ruler Saturninus and that Titus’ overwhelming desire to be everything to Rome is detrimental to the rest of his life. Saturninus’ consideration of Titus as a threat to his power is beyond Titus’ control. Titus would have had to have been defeated in war for that to happen. Secondly, the first decision he makes when arriving home triumphant, to show no mercy and sacrifice Alarbus, is his first big mistake. He could probably have prevented all that happens to his family based on this decision, as Tamora would have had no reason to take revenge on all Andronici (if one assumes she would actually act differently). Finally, the third branch is Titus’ revenge. His revenge leads to pretty much every main character’s death, including his own, except for Marcus, Lucius, and Lucius’ son (and some minor characters who only appear once).

Who is the most murderous character? Why it is Titus! Fifteen people die, and it is Titus who kills the most at six murders: Alarbus (he does not actually do the deed but does pronounce his fate), Mutius (his son), Chiron, Demetrius, Lavinia (his daughter), and Tamora. So although the reader is supposed to be sympathetic to Titus, considering what he has sacrificed for Rome (or maybe disgusted by him as he puts Rome before his family – who knows?), he is actually the most murderous person in the play. So, how is the reader/playgoer supposed to feel about Titus knowing that he is responsible for most of the killing? He does start it after all. Should I feel sympathetic and argue that he is forced to take revenge or argue that his actions at the beginning of the play decide his fate? After seeing the map I would have to say that he brings on his own doom. Saturninus is next with four murders/executions: Quintus and Martius (Titus’s sons) – actually, they could be attributed to Aaron who frames them but Saturninus does give the order so… Saturninus also hangs the hapless clown who conveys Titus’ message (offstage), and stabs Titus. Lucius and Aaron are tied at two murders each. Lucius kills Saturninus and has Aaron executed (offstage), while Aaron kills both the nurse and midwife (offstage) who witness the birth of his son with Tamora. Finally, Tamora’s sons only kill one person, Bassianus, but commit the most heinous crime of the play (in my opinion), the rape and mutilation of Lavinia. Although Tamora eating her sons is pretty gruesome. As a reader (or watcher) one starts to wonder as the play progresses (and the bodies pile up), who is next and how will they die? I feel that any deeper meaning the play might offer is subsumed by the salaciousness of the relentless violence. Even the map ends up providing only a list of who does what to whom. Therefore, I’m not sure if the map helped me see clearer at all, it just made it easier to count the bodies.

I got ideas for mapping not only from Moretti’s “Tree of Culture” (54), but on the Internet as well. I have never made a mind map before and I found that the mind maps I Googled were precisely what I was envisioning in attempting to map the play. I was old school in that I used pencil and paper to draw the map. I decided to mark every murder with drops of blood and big events with symbols I could draw. Unfortunately I cannot draw so that is why the map is pretty bare. Next time, however, I will indicate more clearly who kills whom, so that it is easier to see.

Originally, I had wanted to map out the possible consequences of Titus making different choices in his life. What if he had died and Rome had lost? What would that story be? What if he had shown mercy to Tamora and not killed Alarbus? Would that have given him a “happily ever after? (Would not be much of a story though.) What about not insisting Lavinia marry Saturninus? It leads to him killing Mutius. I soon realized, however, that the “Choose your own Adventure” route for Titus would probably make a pretty boring play, or not.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63.

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. The Norton Shakespeare: Based on the Oxford Edition. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. New York: Norton & Company, 1997. 371-434. Print.

The post Bootcamp: Tree Map, Murder, and Mayhem in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus appeared first on &.

]]>